A personal synthesis

The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me

Blaise Pascal

Where are They?

Enrico Fermi

Introduction

The subject of “aliens”, i.e., beings elsewhere in our universe[1], has captivated my imagination ever since I read Jules Verne’s novel From the Earth to the Moon and its sequel Around the Moon, at the age of nine. By my tenth year I waded valiantly through a treatise that more than stretched my 4th grade intellect: Do Other Inhabited Worlds Exist? (1941) by the Jesuit Catalan astronomer Ignacio Puig wherein he argues, predictably, against that possibility on Catholic theological grounds. Since I did not labor under such religious constraints, I soon tended to believe that we were not alone in the cosmos. My views on this matter, however, subsequently underwent an evolution as I delved into the writings of astronomers, cosmologists, astrophysicists, as well as biologists, geologists and, more lately, astrobiologists. I will endeavor to describe the results of that intellectual evolution in subsequent sections of this essay.

The question of the existence of other inhabited worlds is by no means of recent appearance. Many thinkers in Antiquity broached it, especially in ancient Greece and the Greco-Roman world at large. As expected, such flights of fantasy were subsequently largely absent or suppressed from learned thinking during what we call the Dark Ages of medieval Europe, except for the Islamic Golden Age. They resurfaced mainly in the 15th century becoming widespread among astronomers and many philosophers during succeeding centuries. The interest in this matter has further escalated and became more widespread in the last two centuries as we will review further on.

I will then endeavor to present the various views on the subject that have been espoused and taken hold over the past decades in light of the rapid expansion of our knowledge about our universe and the discoveries that have occurred and continue to occur as the tools for such investigations have become ever more powerful. These recent evolutionary facets have also resulted in controversies that are worth mentioning and that are very much part of the fabric of genuine scientific pursuit.

I will also attempt to reach a set of conclusions based on our present knowledge that reflect my personal thinking hopefully grounded on logically structured premises[2].

Quite A Bit Of History

As expected, philosophers and scientists of Ancient Greece were the intellectual groundbreakers delving into the question of extraterrestrial inhabitants. Here, we should emphasize a clear difference between our contemporaneous thinking and that which preceded it until about the beginning of the 20th century. At present, we make a clear distinction between the concepts of extraterrestrial life and what we call “intelligent” life. No such distinction was made until knowledge about deep geological time and Darwinian evolution took hold towards the end of the 19th century. Previously, it was simply assumed that all forms of life as we know them here on Earth were either eternal or had appeared concurrently (or were created over six days).

Further, as Steven Dick discusses in his magisterial Plurality of Worlds: The Extraterrestrial Life Debate from Democritus to Kant, the prevailing concept in the past, especially during the Greco-Roman antiquity, was that any other inhabited “world” would be another version similar to ours, including our solar system and its complement of – assumed neighboring – stars. The concept of living beings different from those on Earth was seldom part of the discourse – perhaps with the exception of mythical centaurs – until the Middle Ages when an entire zoo of strange beings, on our own planet, such as creatures with a single foot, eyes on their shoulders, mouths on their stomachs, cynocephali, etc. was believed to inhabit the mythical kingdom of Prester John.

In Greco-Roman antiquity two schools of thought stood out as far as the concept of extraterrestrial beings is concerned: the atomists and the Aristotelians. The former of these trace their origin to Leucippus (about whom little is known) and to Democritus (c. 460 – c. 370 BC) who is primarily known for his conceptualization of an early atomic theory of matter. Subsequent followers of atomism were Epicurus (341 – 270 BC) and the Roman poet Titus Lucretius Carus (99 – c. 55 BC). Aristotelians were followers of the ideas of Aristotle (384 – 322 BC). Atomists embraced the idea of a multitude of worlds whereas Aristotelians believed in the uniqueness and centrality of the Earth. It is worth citing here the words of Lucretius in his sole known opus magnum, De Rerum Natura (The Nature of Things) a treatise in verse that was rediscovered by Poggio Bracciolini in 1417 in a German monastery:

“Therefore in similar wise you must admit

that sky, sun, moon, sea and all the rest

are not unique but numberless in number;

for their life’s limits are deeply set

and their identities are as much created

as all our myriad things here, kind by kind.”3

Aristotle and his school of thought, on the other hand, believed in a geo-centered universe and that the Earth was the sole abode of living beings, a world view that

3 Lucretius, De Rerum Natura, Book II, 1080-1085

persisted throughout the middle ages and beyond, especially within the realm of Catholic theology, at least until the 17th century.

Starting in the 13th century, philosophers and theologians engaged in speculations about the existence of “other worlds”. The arguments centered principally around God’s intention and omnipotency. The Aristotelian legacy dictated Earth’s uniqueness and centrality thus ruling out the possibility of such worlds. On the other, hand, alternative ideas led to speculation that since God’s capabilities are unlimited, the divinity would not be restricted to the creation of our singular world.

Deviations from the Catholic orthodoxy and Aristotelianism began to appear in the late Middle Ages. Remarkably, one of the princes of the Church, Nicolas de Cusa (1401 – 1464), opined that the earth is a star like other stars, is not the center of the universe and accepted the possibility of the plurality of inhabited worlds. Even earlier, the philosopher Nicole Oresme (c. 1325 – 1382) espoused similar ideas. It is worth pondering why it was possible to express such “deviant” views in the Catholic realm in the 14th and 15th centuries when, later on, Copernicus (1473 – 1543), Galileo (1564 – 1642) and others either feared persecution or were actually executed such as Giordano Bruno (1548 – 1600), for any heterodoxy in such matters. I tend to attribute such hardening by Church authorities to the spirit of the Counter-Reformation elicited by Martin Luther’s pronouncements of 1517. Thereafter, any manifestation of perceived heresy resulted in persecution by the Church.

Speculations about extraterrestrial life then became restricted to the Protestant world. Curiously, a revisionist religious argument became prevalent, especially as a result of telescope mediated observations of the heavens. These observations revealed a plethora of new cosmic bodies – stars and nebula – outside our solar system that had previously been unknown. This, in turn, elicited the view that there had to be a divine purpose for the existence of such, heretofore, unseen worlds. Why would God create all those cosmic bodies without witnesses? The underlying thought was that everything that existed, i.e., the universe, had to have a purpose to justify its existence. Thus, these newly discovered worlds needed to be inhabited to bear witness to the glory of God. Whereas theological reasons were previously invoked to condemn such ideas, starting in the 17th century, religion became the basis for the belief in the plurality of inhabited worlds. These ideas were further supported by the atomist philosophy promulgated by the much admired poet/philosopher Lucretius who influenced many of the astronomers and other thinkers starting in mid-16th century and continuing well into the 18th. Thus, Galileo, Bruno, Kepler and Newton were influenced by the Greek atomists through the verses of the Roman poet.

The belief in the plurality of inhabited worlds was further supported by the growing realization that the stars were so many other suns from which the assumption of the existence of other solar systems with inhabited planets followed.

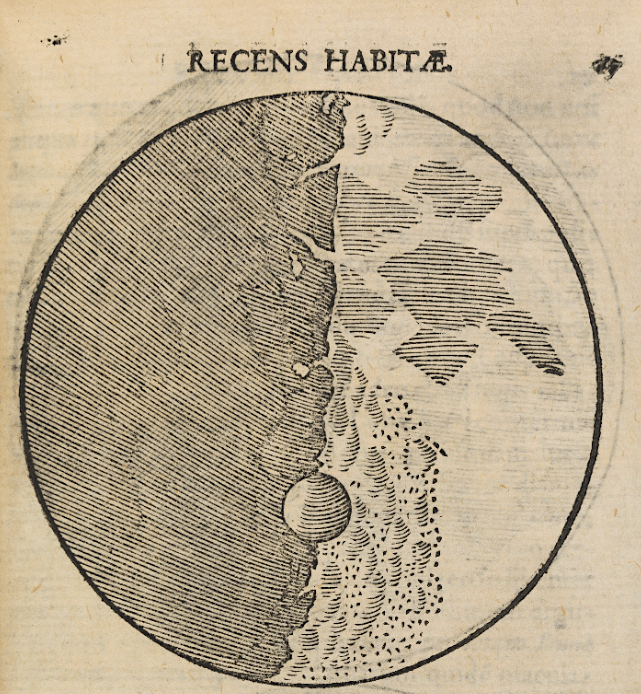

Within our own solar system, the observations of mountains on the Moon by Galileo suggested to him and Kepler (1571 – 1630) — they communicated with each other — about the likelihood of Earth-like conditions on our satellite and, consequently, the existence of plants, animals and humans on the Moon. Similarly, they considered such habitability for the recently discovered satellites of Jupiter. Again, the prevailing underlying logic was that the existence of such worlds had to be justified by a purpose. Here is what Kepler wrote: “The conclusion is quite clear. Our moon exists for us on earth, not the other globes. Those four little moons exist for Jupiter, not for us. Each planet in turn, together with its occupants, is served by its own satellites. From this line of reasoning we deduce with highest degree of probability that Jupiter is inhabited.”

The 16th and 17th centuries saw a plethora of writings about the subjects of multiple worlds, infinite numbers of solar systems, hypothetical inhabitants in other planetary systems, etc. Notable writers, philosophers and scientists especially in France and England expressed a variety of ideas and hypothesis of the matter. Among them we can mention Michel de Montaigne (1533 – 1592), Pierre Gassendi (1592 – 1655), Henry More (1614 – 1687), John Wilkins (1614 – 1672), René Descartes (1596 – 1650), Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle (1657 – 1757), the Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens (1629

– 1695) and the English astronomer Thomas Wright (1711 – 1786). Detailed and learned accounts of the ideas of each of these thinkers can be found in the previously mentioned book by Steven Dick, Plurality of Worlds. Among these writers it is worth mentioning Fontenelle, a colorful Enlightenment figure, who wrote the influential Entretiens sur la pluralité des mondes, wherein he presents his ideas about the plurality of inhabited worlds in the form of a series of conversations between a gallant philosopher and a marquise. This work was to be quite popular in the late 17th century. As expected a more scientific approach to the subject characterizes Huygens’s treatise Cosmotheoros, an influential work by that notable Dutch astronomer.

As to the great Isaac Newton (1643 – 1727), he was loath to express specific opinions about the existence of other inhabited worlds, although he did not deny its possibility.

A notable proponent of the plurality of inhabited worlds, in particular those centered around an infinite number of stars, was the great Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804) whose Allgemeine Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels (Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens) stands out as a major European Enlightenment contribution to the subject. The great French astronomer Pierre Simon de Laplace (1749 – 1827) considered the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence as most likely. As we will discuss later on, Laplace’s nebular hypothesis of the formation of solar systems closely resembles 21st century’s ideas.

It is worth inserting here Steven Dick’s summary about the Enlightenment’s position on this subject: “The universe of Wright, Kant and Laplace, the heritage of Isaac Newton’s universe and the progenitor of today’s, was one in which the existence of extraterrestrial rational beings was of utmost significance. In this historical fact is found the impetus for the controversy that has continued ever since, and that remains unresolved today.”

We can therefore state that by the 1800s and well into the 20th century, the existence of other inhabited worlds was no longer questioned by the majority of thinkers, although opposing anthropocentric ideas were espoused by those who believed in the uniqueness of humans and the centrality of the solar system within the universe, such as Alfred Russel Wallace (1823 – 1913) famous for being the competing proponent of the theory of evolution. He stated in 1903 (see Life on Other Worlds by Steven J. Dick) that: “Our position in the material universe is special and probably unique, and … it is such as to lend support to the view, held by many great thinkers and writers today, that the supreme end and purpose of this vast universe was the production and development of the living soul in the perishable body of man”, an almost medieval view reflecting Wallace’s religious approach to the subject. It is worth mentioning at this juncture that solipsistic views (i.e., that the Earth is likely to be unique) are, at present, very much part of the scientific discourse but for reasons that are entirely different, than those motivating Wallace more than a century ago, as we will discuss later on.

Immanuel Kant, Johann Gottlieb Becker – Schiller-Nationalmuseum. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

It is also worth mentioning, among the pluralists (those who espouse the plurality of inhabited worlds) of the 19th century the well known French astronomer Camille Flammarion (1842 – 1925) who forcefully advocated – in his 1862 La pluralité des mondes habités – the case for the multiplicity of advanced extraterrestrial intelligence based on Darwinian evolution considerations.

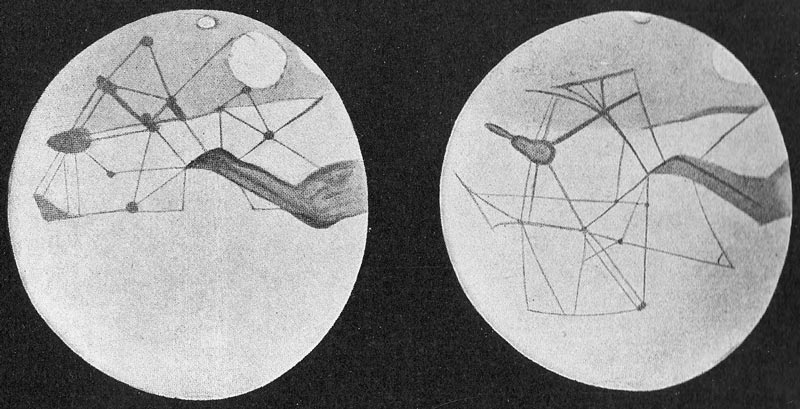

The supposed observational confirmation of the existence of extraterrestrial civilizations reached a feverish culmination around the turn of the 19th into the 20th century with the purported discovery of Martian “canals” by the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli (1835 – 1910) and the belief by the American astronomer Percival Lowell (1855 – 1916) that these canals were part of an elaborate irrigation system created by an advanced civilization. The very existence of such canals on Mars was eventually disproven as an illusion, after much acrimonious debate.

The fluctuating views about the prevalence of inhabited worlds that was to characterize much of the discourse during the 20th century and beyond can be exemplified by the widely accepted and eventually discredited Jeans-Jeffreys tidal hypothesis (1917) of the formation of our solar system by the improbable grazing of the Sun by another star that tore a filament from the former from which the planets would originate. The genesis of the solar system was therefore considered a very low probability occurrence that would imply the formation of other planetary systems as extremely unlikely.

Consequently, the existence of other inhabited worlds had to be correspondingly improbable. James Jeans (1877 – 1946) was a very respected British astronomer (he was knighted in 1928) who stated well into the 20th century “All this suggests that only an infinitesimally small corner of the universe can be in the least suited to form an abode of life” (see Life on Other Worlds by Steven J. Dick). Equally famous astronomers such as Sir Arthur Eddington (1882 – 1944) were to endorse Jean’s hypothesis. By the early 1940s, however, the tidal mechanism of planet formation had been thoroughly discredited by observational evidence and theoretical considerations, reviving a variation of Laplace’s 18th century’s solar nebula planetary genesis, a formation process that did not have to invoke improbable events. As we will see later on, the discovery of a plethora of exoplanets starting in the mid-1990s was to lend strong support to a totally different view about potential abodes of extraterrestrial life.

During the 20th century, principally as a result of Darwinian evolution considerations and the overall developments in the biological sciences, a dichotomy ensued between the concepts of life and “intelligent” life elsewhere in the universe. That distinction has become crucial in the overall search of extraterrestrial beings.

Two purported sites of advanced civilizations — Martian canals depicted by Percival Lowell. Source: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain {{PD-US-expired}}

The Drake Equation

Starting in 1961, the extraterrestrial life discourse has shifted from a purely speculative realm to a more quantitative approach, i.e., a probabilistic attempt to identify the factors that could determine the existence of life, especially intelligent life, elsewhere in our Milky Way galaxy. It was the American astronomer Frank Drake (born 1930) who developed an equation – now known as the Drake Equation – that summarized those factors that could be considered when attempting to predict the probable number of technologically communicative civilizations within our galaxy.

The following is the Drake equation:

where:

N = R* fp ne fl fi fc L

N = the number of civilizations in our galaxy with which communication might be possible;

R* = the average rate of star formation in our galaxy (1 per year);

fp = the fraction of those stars that have planets (0.2 to 0.5);

ne = the average number of planets that can potentially support life per star that has planets (1 to 5);

fl = the fraction of planets that could support life that actually develop life (1);

fi = the fraction of planets with life that actually go on to develop intelligent life (civilizations) (1);

fc = the fraction of civilizations that develop a technology that releases detectable signs of their existence (0.1 to 0.2);

L = the length of time during which civilizations release such signals (1000 to 100 million).

The numbers in parenthesis represent the range of original estimates published by Drake.

Inserting the minimum estimated values in the equation yields N = 20. Using the maximum values mentioned above gives 50 million. That range is symptomatic of the

enormous uncertainty of the factors of the equation. Inserting the most recent estimates of the factors of the Drake equation yields a range of N = 10-12 (suggesting we are alone not only in our galaxy but in the observable universe), to N = 16 million. This extremely wide range once more indicates that we do not know enough to make meaningful use of the Drake equation at this time.

Since Drake developed his eponymous equation, several modified versions have been proposed, notably that by P. D. Ward and D. Brownlee in Rare Earth: Why Complex Life is Uncommon in the Universe. These authors broadened the equation to include several additional contingent factors that very much reduce the probable value of N to yield the most recent minimum which implies that we may be the sole technologically communicating species within, at least, our Milky Way galaxy. I will address further on some of these additional “rare Earth” constraints.

It is of interest to note that since mid-20th century members of the astronomical community have tended to embrace the pluralist point of view of planets inhabited by advanced civilizations whereas the opposing solipsistic point of view has been most frequently expressed by biologists and geologists. The well known astronomer Carl Sagan (1934 – 1996) exemplifies the enthusiastic proponents of a multiplicity of civilizations in our galaxy whereas influential evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr (1904 – 2005) belongs to the opposing camp. The latter takes the position that life itself, especially in its most basic forms may well exist throughout our galaxy and beyond but that intelligent technologically advanced forms of life such as homo sapiens are unlikely to have developed elsewhere. Sagan disagreed with that limitation and embraced the view that electro-magnetically communicating civilizations are inevitable end-points of evolution. This latter view underpins the inception and continuance of SETI, the Search of Extraterrestrial Intelligence. Mayr disputes the justification for that search as a futile endeavor. See more about SETI further on.

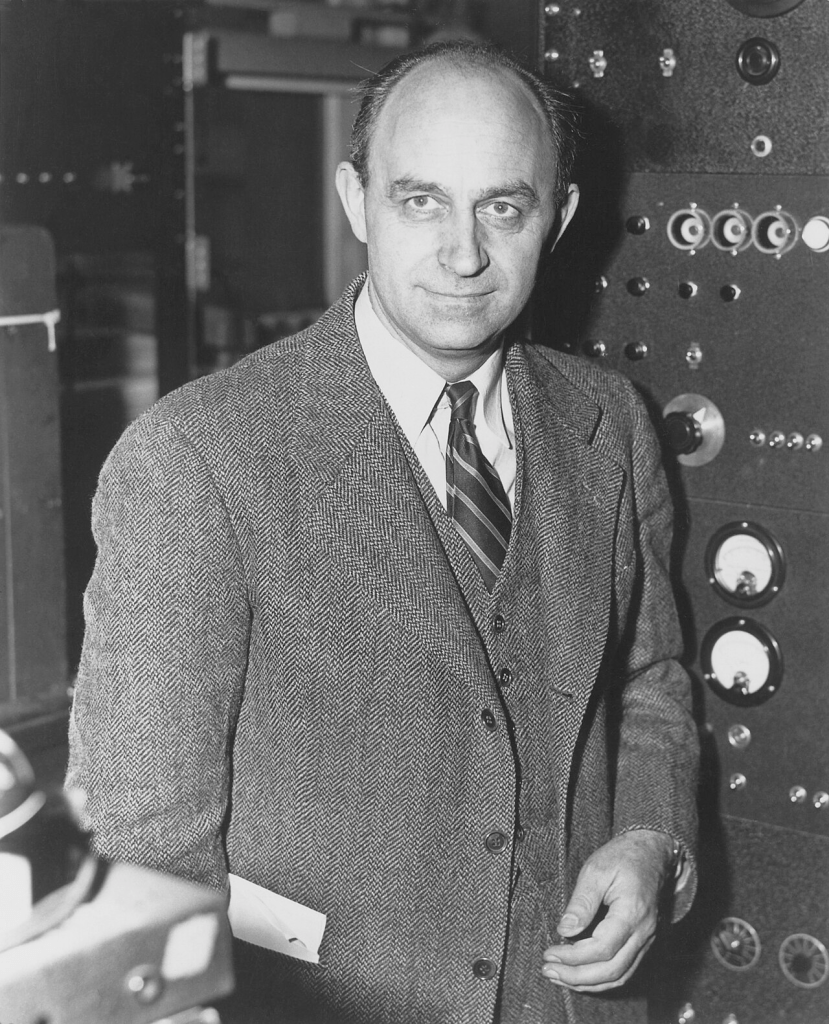

Fermi’s Paradox

About the year 1950 the notable Italian nuclear physicist and Nobel prize winner, Enrico Fermi (1901 – 1954), during a lunch with colleagues at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, during which they were discussing the current craze about flying saucers, asked a — now iconic — question: “If there are extraterrestrials, where are they?”. To which a glib satirical answer has also become iconic: “They are here and are called Hungarians” reflecting the unusual number of outstanding scientists who emigrated to the United States during the mid-20th century (e.g., von Neumann, Szilard, Wigner, von Karman, Szent-Gyoryi, Gabor, Teller, etc). Fermi’s Paradox has become the embodiment of the total absence of any indication of the existence of extraterrestrial intelligence either in the form of evidence of past or present visitation by aliens, through electromagnetic signals, or any other manifestation that could be attributed to such non-human civilizations. This total dearth of evidence has been adduced against the pursuit of SETI.

The enthusiastic advocacy by Carl Sagan in favor of SETI during the last three decades of the 20th century epitomized the attitude of many astronomers who looked at the problem as one that was justified on the assumption that a large majority of stars was accompanied by a retinue of planets among which many would inevitably be Earth-like and reside in orbits compatible with the presence of liquid water on their surfaces, a necessary ingredient of life. Sagan, in his otherwise entertaining book “The Cosmic Connection” (1973), went so far as labelling the disbelievers in the multiplicity of extraterrestrial civilizations as “Chauvinists”, i.e., cosmic nationalists who believed in the uniqueness of our human civilization.

Sagan’s pluralistic view saw itself increasingly challenged during and after the 1990s by a host of scientists who approached the question from a more biological and evolutionary point of view following the above mentioned example of Ernst Mayr. More and more the problem of biological, geological, climatic, astronomical and other contingencies has forced the rethinking of the plausibility of the development of advanced intelligent life. I will address this, so called, Rare Earth argument in due course.

In any case, there is no doubt that Fermi’s question has, since its pronouncement, sparked much attention, debate and general interest in the question of extraterrestrial civilizations.

A Surprising Essay

The subject of extraterrestrial life has preoccupied many a scientist in the past but surprisingly also none other than a very famous politician. I am referring to Winston Churchill! Apparently he penned the initial draft of an essay entitled “Are We Alone in the Universe?” in 1939, when Britain was on the brink of World War II and completed it about a decade later, under more peaceful conditions, while he was vacationing in the south of France.

This essay is truly remarkable because it reflects a thorough understanding of the question. Churchill approaches it with the logic and skepticism of a true scientist.

For those interested in the latest article on this essay: Livio, M., “Winston Churchill’s essay on alien life found”, https://www.nature.com/news/winston-churchill-s-essay-on-alien-life-found, 15 February 2017.

Here, it will suffice to summarize the principal points of Churchill’s essay. He starts by stating that “all living things of the type we know require water”, very much in line with the present consensus. He considers that the model of planetary formation postulated by James Jeans in 1917 (see discussion above) would imply rarity of planets elsewhere but then states “but this speculation depends on the hypothesis that planets formed in this way. Perhaps they were not. We know there are millions of double stars, and if they could be formed, why not planetary systems?”. He then continues “I am not sufficiently conceited to think that my sun is the only one with a family of planets”. Churchill then considers that “some planets will be at the proper distance from their parent sun to maintain a suitable temperature” to ensure the presence of liquid water.

The essay concludes: “with hundreds of thousands of nebulae, each containing thousands of millions of suns, the odds are enormous that there must be immense numbers which possess planets whose circumstances would not render life impossible”. He also affirms that “I, for one, am not so immensely impressed by the success we are making of our civilization….or that we are the highest type of mental or physical development which has ever appeared in the vast compass of space and time”.

Churchill was a fervent admirer of science and fully relied on scientists to advise him on such matters. One wishes that such views would always be espoused by our political leaders.

The Great Exoplanet Discovery

For hundreds of years, ever since it became an accepted idea that the stars are suns or, conversely, that our Sun is a star, belief in the existence of exoplanetary systems prevailed. If the Sun has a retinue of planets, so should many stars. This pluralistic view predominated starting in the 17th century, notwithstanding those occasionally solipsistic opinions mentioned above. This view stimulated the observational search for extrasolar planets (now abbreviated as exoplanets) principally during the second half of the last century. This search, however, was a challenge to the observational tools of that period. The principal obstacle to the discovery of planets rotating around other stars than the Sun resides in the difficulty of detecting the minute amount of reflected light reaching us from such planets against the overwhelming glare of their host stars.

The discovery of the first exoplanets was made possible by a combination of technological advances, principally in the areas of spectroscopy, electronic detection and signal analysis, as well as computer processing. It was thus that the first exoplanet was discovered around a main-sequence star, such as the Sun, in 1995 by two Swiss astronomers – who thus obtained the Nobel prize in 2019 – using an indirect method of detection, the radial-velocity method. This method and others now being applied will be discussed further on. As of 7 November 2024, there are 5,787 confirmed exoplanets in 4,320 planetary systems, with 969 systems having more than one planet.

Once such a plethora — largely unexpected — of exoplanets was discovered that statistically suggested that essentially every star in the Milky Way galaxy, at least in our vicinity, hosts a planetary system, the search has been concentrated on Earth-like planets likely to be the abodes of life, whether intelligent or not.

There have been already a number of surprising and unexpected discoveries about exoplanets during the initial decades since the first one was identified in the mid-1990s. Principally, and against all expectations, exoplanetary systems do not resemble our Solar System. Sagan, in the aforementioned book, had presented five computer generated models of likely solar systems that clearly emulate our own planetary system. Prior to the discovery of exoplanets it was assumed that the

processes of formation of any other system would follow that of the Solar System such as rocky, smaller planets would orbit closer to the host star, whereas gas giants would tend to occupy orbits farther out. Also, it was assumed that all planets of other systems would reside in orbits no closer to their suns than Mercury. Exoplanet observations have shown that our system is far from being typical and that there exists an enormous variety of planetary systems. For example, a large number of them contain hot-Jupiter planets in exceedingly tight orbits (e.g., NGTS-10b with a mass of

2.16 times that of Jupiter, with a period of merely 0.7669 days (18.4 hours), as compared to our Jupiter whose period of rotation around the Sun is 4,333 days (11.9 years). Other idiosyncrasies of exoplanets are the frequent presence of super-Earths (rocky planets larger than the Earth), small-Neptunes, etc. Some systems have only rocky planets, some only gaseous ones. For example, the Trappist system consists of an ultra-cool red dwarf star accompanied by 7 rocky planets all of which reside in orbits that would fit inside that of Mercury around the Sun. The Trappist planets range in mass from 0.3 Earths to 1.16 Earths. Such systems were not predicted theoretically and illustrate the complexity and variability of the formation process of solar systems.

It is sad to reflect on the premature passing of Carl Sagan in 1996, at the dawn of the exoplanet era. He would have been both thrilled by the discoveries that followed while also surprised about the unexpected variety of systems with planets of sizes and orbits differing radically from those of our Solar System. Although Sagan had predicted that many stars are accompanied by planets he would also have been surprised by the abundance with which such planets appear, i.e., recent observations suggest that almost every star has one or more planets.

As mentioned above, exoplanets are detected generally by indirect methods, i.e., not directly observational, such optical detection being generally precluded because the amount of reflected light reaching us from those planets is totally swamped by the glare of their host star. Initially, the only successful method was based of the detection of the minute Doppler effect shifting the spectral signature of the star light due to the gravitational tugging associated with a planet orbiting the star. This is the radial velocity method alluded to previously. More recently (since 2004), and using the Kepler space telescope, the transit method of detection has become the preferred one. It consists of detecting the small decrease of the light received from the star as a planet passes between the star and the Earth, i.e., a mini-eclipse. This latter method is obviously limited to those cases where the exoplanet orbits its star in or near a plane containing the star-Earth line of sight. Other techniques of detection, such as gravitational lensing and direct photometric detection, are used only rarely. The transit method provides information about the size of the exoplanet and its orbital period whereas the radial velocity method yields the mass and orbital period. Combining the data from these two methods yields exoplanet density (which distinguishes between rocky and gaseous planets), orbital eccentricity, orbital angle, and related parameters. Spectral analysis of the star light as an exoplanet passes in front of and behind the star can provide information on the presence and composition of an exoplanet’s atmosphere.

Eventually, it is believed that such spectroscopic characterization may yield information on the possible presence of life forms by detecting the presence of oxygen, ozone and methane in more than trace amounts, the signatures of biological modification of the environment.

The discovery of exoplanets has shed new light on two of the parameters of Drake’s equation: fp the fraction of stars with planets, and ne the average number of planets that can potentially support life per star that has planets. It is hoped that detailed spectroscopy of exoplanetary atmospheres may, in the future, yield information on fl the fraction of planets that could support life that actually develop life.

Results, so far, seem to indicate that a sizable fraction of stars are accompanied by planets that are potential abodes of life forms. The consensus is that the principal criterion bearing on the probability of life is that the surface temperature and atmospheric pressure on a planet be compatible with the presence of water in the liquid phase. Temperature is generally derived from the irradiation level received by the planet from its host star. This condition is fulfilled within a range of distances from the star where the temperature is above the freezing point and (well) below the boiling point of water. This distance gap is often referred to as the “Goldilocks” zone. Furthermore, an equilibrium temperature (i.e., the temperature of a planet in the absence of an atmosphere) is computed from the surface temperature of the star, the distance between star and planet, and the planet’s albedo. This latter parameter is usually assumed since it is not easily measured. Equilibrium temperature, however, is not sufficient to determine the actual surface temperature of an exoplanet. It ignores the role of the greenhouse effect, i.e., the trapping of heat due to selective atmospheric spectral absorption. This factor can only be ascertained by detailed determination of the composition and pressure of the exoplanet’s atmosphere or by direct measurement of surface temperature which have been achieved only to a limited degree to date.

The presence of liquid surface water is considered not only essential as a building block for life but it plays an important role in preventing a runaway greenhouse effect as that of the planet Venus. The planetary atmospheres during their early phases contain high levels of carbon dioxide resulting in warming well above the equilibrium temperature. Large oceans such as those on Earth are effective carbon dioxide sinks thus reducing heat trapping in the atmosphere.

The following figure is a simplified diagram of the basic steps that are and will be applied to assess the possibility of the presence of life on an exoplanet. This procedure is based on combining the parameters of the host star with those of its exoplanet, whose properties are determined from the two detection methods mentioned above, i.e., the radial velocity and transit methods. From these two methods it is possible to derive the density of the exoplanet which determines whether it is a rocky or a gaseous one. From the orbital period of the exoplanet and the mass of the star one derives the distance between the two. This distance in combination with the temperature of the star determines whether the planet is in the habitable zone, i.e., wherein surface liquid water may exist. Transit spectroscopy, from which planet atmospheric composition and pressure can be obtained, may then determine whether the exoplanet suggests the presence of life. For example, the presence of a significant fraction of oxygen and of methane could be interpreted as manifestations of life forms that have modified the planet’s atmosphere.

As an example of the potential effect of the greenhouse effect we can cite the case of Venus in our Solar system. The calculated equilibrium temperature at the surface of Venus is 227 K (-51 0F), however the actual temperature is 740 K (873 0F)! Compare that to the Earth for which the equilibrium temperature would be 255 K (0 0F), whereas the actual average surface temperature of the Earth is 288 K (59 0F). Astute readers would question how the equilibrium temperature of Venus could possibly be below that of the Earth! (Venus is after all closer to the Sun than the Earth). The reason for that apparent paradox is that the albedo of Venus is much higher than that of the Earth because of the complete white cloud cover of Venus which reflects much of the incoming solar radiation. The above example cautions against using the Goldilocks criterion to define the habitable region surrounding a star: Venus would have qualified as such were it not for its extreme greenhouse effect. The case of Mars is also illustrative: because of its very tenuous atmosphere, that planet’s surface has an actual temperature that barely differs from its equilibrium value.

It is of historical interest to note that the first scientist to attribute to a greenhouse effect the discrepancy between actual and equilibrium temperatures of the Earth was the French mathematician Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier (1768 – 1830), nearly 200 years ago. Shortly after, the Irish scientist John Tyndall (1820 – 1893), in the mid-1800 was to state: “Without water vapor, the Earth’s surface would be held fast in the iron grip of frost”, a poetic musing about the Earth’s 0 0F equilibrium temperature, i.e., in the absence of an atmosphere, mentioned above. It should be noted that in Tyndall’s time the greenhouse contribution of anthropogenic atmospheric carbon dioxide was small compared to that of water vapor, in contrast to the present situation.

Two pioneers of the greenhouse effect

Summarizing the latest results from exoplanets observations in the context of what concerns this essay, the number of potentially habitable planets, at least within our galactic neighborhood, is significant: of the order of millions. This, at least prima facie, would appear to support Sagan’s sanguine support of a galactic multiplicity of civilizations. I will delve deeper into this conclusion and dissect it carefully in subsequent sections of this writing. A very different perspective will emerge, however.

SETI – The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence

To begin, I need to define what is meant by Extraterrestrial Intelligence. Intelligence, per se, is a complex concept whose definition is by no means straight forward and widely agreed upon. Recent animal behavioral studies have unequivocally debunked the idea that only homo sapiens is blessed with “intelligence”. It has become generally agreed today that many different species of animals exhibit intelligence such as several primates, canids, cetaceans, as well as birds such as corvids and even chickadees. In the context of SETI we have to narrow down the concept of intelligence to that of Technologically Communicating Intelligence (TCI) a level that, on Earth, humanity alone has achieved and only very recently, that is within the last one hundred years, or so. To search for alien intelligence that has not reached the capability of using electromagnetic waves to both detect and transmit information is most probably impractical if not impossible given that actual interstellar travel is likely to remain in the realm of science fiction, perhaps even for hypothetical more advanced civilizations.

SETI was initiated by Frank Drake, the author of the eponymous equation discussed above, in 1960 as Project Ozma. Two methods of communication with candidate extraterrestrial civilizations were thus initiated: passive and active.

Passive communication consists of listening to electromagnetic signals — technosignatures — originating from such civilizations, These signals could either be generated intentionally to possibly establish two-way communication, or be an unintended byproduct of “local” communication or cultural activities by such an alien civilization. In the case of our own planet, this latter case is exemplified by various broadcasting media (radio and TV), radar emissions, etc. It has been pointed out that Earth’s artificial electromagnetic emissions has resulted in an unintended wave front propagating outward into space with a present radius of the order of 100 lightyears, i.e, any advanced alien civilization within about 100 lightyears would, by now, be aware of humanity’s existence, albeit through a rather chaotic leakage of our signals. In general, passive SETI must be considered the only potentially successful approach since it could detect TCI signals generated at great distances from the Earth.

Active SETI consists of beaming out electromagnetic signals in specific directions, preferably towards promising targets, e.g., nearby exoplanets such as Proxima Centauri b, the closest of all exoplanets, at a distance of only 4.24 lightyears from the Earth, which orbits in the habitable zone of the red dwarf star Proxima Centauri. In the improbable case that this exoplanet is inhabited by a TCI civilization, a response signal could arrive back on Earth some 8.5 years after we beam out a signal. The justification for active SETI becomes rather questionable for much larger distances given the requirement for roundtrip communication. I, for one, cannot see the logic behind such quixotic undertakings as that performed in 1974 when a message was sent from the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico towards a globular cluster 25,000 lightyears away followed by several other such transmissions. A globular cluster had been selected as a target on the assumption that such star groupings consist principally of older stars thus raising the probability of the development of more advanced alien civilizations.

Also, clusters present an angularly concentrated target of many stars, enhancing the probability of reaching a potential alien civilization. But, What is to be achieved with such a remote hypothetical correspondent? The earliest response would arrive back at Earth in 50,000 years, hardly a justification for such a transmission.

The renowned astrophysicist Stephen Hawking was emphatically opposed to active SETI for an altogether different reason. He argued that “alerting aliens of our existence is foolhardy”. Hawking cited the sorry precedent of colonial oppression and slavery meted out by Europeans on encountering other peoples they considered inferior.

Passive SETI, on the other hand, is obviously devoid of that danger.

Recently, an open competition has been announced whose aim is to design a digital message to be beamed out, notwithstanding Hawking’s reservation, and not before an international debate on the risks and rewards of contacting advanced civilizations. This is called the Breakthrough Message and it carries a $1 million prize.

Listening to any incoming signal, i.e., passive SETI, makes a lot more sense. It is not limited by distance, except in so far as signal intensity is concerned, requires little energy compared with that required by high powered transmission systems, can be performed over a wider frequency spectrum, and last but not least, requires no lengthy round-trip waiting time such as that of active SETI.

Passive SETI has seen many ups and downs over the years since its first inception in 1960. For some time it seem to be sufficiently funded and viable. In fact a major distributed computer program was implemented as SETI@home with up to 5 million participants worldwide in order to automatically sift through the exceedingly large data flow of signals gathered by several radio-telescopes. But by the first decade of the 21st century, much of the interest in this project appeared to have waned as none of the detected signals could be attributed to an extraterrestrial civilization. SETI@home has been terminated in 2020.

A significant revival of SETI has occurred since January of 2016 when Project Breakthrough Listen was initiated with $100 million funding, over a period of 10 years,

supported by the billionaire Yuri Milner and based at the Astronomy Department at the University of California, Berkeley. The project uses both radio waves and visible light observations. Targets are signals from: a) all stars within 16 lightyears, b) 1000 stars of all spectral types within 160 lightyears, c) 1 million nearby stars, d) exotic stars such as 20 white dwarfs, 20 neutron stars and 20 black holes, and e) center region of at least 100 nearby galaxies. The objective is to generate as much data in one day as previous SETI projects generated in one year. To date (early 2020s) no so-called technosignatures of civilization have been detected.

What is my opinion about SETI in general and Project Breakthrough Listen, in particular? I will have to get ahead of myself to respond to that question since I will be covering several crucial pertinent arguments in what remains of this essay. My view is that SETI will not achieve a meaningful detection of an unequivocal technosignature signal and that Fermi’s question will remain unanswered. But, I still believe that there is sufficient justification for the pursuit of SETI in that, by a null result, it will have sweeping implications as to the likelihood that we are alone, at least within the Milky Way galaxy, if not in our universe at large.

The Rare Earth Hypothesis

As mentioned previously, and as biologists, geologists and other scientists than astronomers have begun to ponder the questions of extraterrestrial life and technological intelligence, questions have been raised about the abundance and even existence of such alien forms. Ernst Mayr (1904 – 2005) was perhaps the first of the more notable scientists to question the assumption of a multiplicity of TCI civilizations while accepting the widespread existence of life itself in its simple and basic forms.

As to intelligent life as we have defined it above, Mayr is quite skeptical. Some of the reasons he adduces for that skepticism will be treated later on when I consider the lessons we can derive from our Earth’s experience.

At the waning of the 20th century and early 21st, several scientific writers have joined Mayr in doubting the multiplicity of worlds inhabited by advanced civilizations. The most influential of these were Peter D. Ward and Donald Brownlee, authors of Rare Earth, Why Complex Life is Uncommon in the Universe, published in 2000. In 2011 John Gribbin published Alone in the Universe, Why Our Planet Is Unique. Both these works come to similar conclusions about the uniqueness of our planet Earth in having produced an advanced civilization.

Ward and Brownlee present the argument in the form of an expanded version of Drake’s equation that incorporates several additional parameters that have come to light since its earlier predecessor. These added factors are:

- fraction of metal rich planets

- stars in galactic habitable zone

- fraction of planets with life where complex metazoans arise

- fraction of planets with a large moon

- fraction of solar systems with Jupiter-sized planets

- fraction of planets with a critically low number of mass extinction events

I should point out that even this added list of factors is not likely to be exhaustive and that new ones are and may be considered in light of recent discoveries. Ward and Brownlee mention two such additional events: the Snowball Earth and the inertial interchange event. The latter is associated with the Cambrian explosion about which we will talk later on. Further, I should mention additional factors likely to be crucial: the fraction of planets with magnetic fields capable to deflect solar high energy radiation, and the fraction of planets that exhibit tectonic dynamics. The combination of all these conditions may be rather unique to Earth. In addition I will address further on relevant factors external to the Earth such as the role played by the Sun’s properties.

I will revisit Ernst Mayr’s views and related subjects when I talk about our Earth’s experience in terms of the development of life and of advanced, i.e., high intelligence life.

Returning to the Rare Earth hypothesis as postulated by Ward and Brownlee, their conclusion is that “it appears that Earth indeed may be extraordinarily rare”.

What Happened On Earth?

I will now address the important subject of the process through which the Earth went in order to culminate with the appearance of humanity and its high intelligence technological capability. It is our only example of such stunning development and we will attempt to dissect the conditions and events leading to this evolutionary achievement. We will have to be careful not to assume that either these events are unique to our planet nor that they commonly occur elsewhere. I will endeavor to remain as objective as possible.

Let us review some basic facts.

Earth was formed about 4.5 billion years ago, essentially as part of the formation process of our Solar System. During the first several hundred million years, the Earth passed through a mostly chaotic period within which its crust solidified, the oceans formed and the surface of the planet was subjected to intense bombardment by mostly smaller bodies that had also formed within the overall Solar system creation. This initial epoch was inimical with the formation and existence of any form of life as we can conceive it. Sometime, 500 to 700 million years after the formation of the Earth, i.e., 3.8 to 4.0 billion years ago, it is believed that the first forms of life appeared. These were very primitive, single cell organisms capable of reproducing and evolving. This fact, generally accepted, is rather remarkable because it implies that life appeared on this planet essentially as soon as the conditions on its surface allowed it to exist. This fact, at face value, has enormous potential implications, it would suggest that given the right conditions life is an inevitable outcome of the formation of a planet. And yet, all

indications suggest that life may have arisen only once, perhaps in one location, because all forms of life that exist and ever existed (based on fossil data) on Earth share a common structure based on the DNA molecule and its chirality. New life forms do not continue to appear on our planet. The extreme complexity of the molecular structure of life on Earth and its processes of replication/reproduction have to be considered when we attempt to predict its abundance in the universe.

The conflicting conclusions, however, which scientists have reached on this matter are exemplified by the following two opinions, cited by Steven Dick in his book Life On Other Worlds:

Alexander Oparin (1894 – 1980), a renowned Soviet biochemist, wrote in 1975: “There is every reason now to see in the origin of life not a ‘happy accident’ but a completely regular phenomenon, an inherent component of the total evolutionary development of our planet. The search for life beyond Earth is thus only part of the more general question which confronts science, of the origin of life in the universe”.

Ernst Mayr, on the other hand, in 1982 affirmed: “A full realization of the near impossibility of an origin of life brings home the point how improbable this event was. This is why so many biologists believe that the origin of life was a unique event. The chances that this improbable phenomenon could have occurred several times is exceedingly small no matter how many millions of planets in the universe.”

Later on I will mention the idea of panspermia, advocated several times throughout history, the transposition of life’s origin to an extraterrestrial source, i.e., the hypothesis that life arrived on Earth during its formative phases.

Abiogenesis is the natural process by which life has arisen from non-living matter. Although the occurrence of abiogenesis is uncontroversial, its actual mechanisms are, so far, unknown. We know that the prevailing conditions on Earth under which life arose were radically different than those at present. Life on our planet is based on the special chemical properties of water and carbon. If we want to determine whether life is widespread in our galaxy and the universe at large, it is imperative to discover life outside our planet, whether fossilized such as, possibly, on Mars or presently alive elsewhere in the Solar system such as on one of the large satellites of Jupiter or Saturn. Should such searches be unsuccessful, we will have to rely on future observations of telltale signs of life on nearby exoplanets, i.e., non-equilibrium atmospheric components associated with the presence of life, as mentioned previously.

Are there any entirely different forms of life in our universe, i.e., not based on water and carbon? Is it a form of “carbon chauvinism”, in the words of Carl Sagan, to believe in the uniqueness of our life’s structure. My view is that Sagan expresses a pseudoscientific “politically correct” attitude symptomatic of the mentality of the 1970s. He mentions conceivable life based on other elements than carbon, such as silicon, germanium, etc. To counter such ideas it is worth mentioning that since 1937, a veritable interstellar chemical laboratory has been discovered, overwhelmingly constituted by carbon compounds that may have been vital in the formation of life on Earth. Starting with CH, since then, some 200 different such molecules have been identified. Included in these interstellar molecules are polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and fullerene. In 2012 glycolaldehyde, a sugar molecule was found; it is the basis for RNA in living organisms. These discoveries, by means of absorption spectroscopy, raise the possibility that life on our planet originated from an early “rain” of some of these carbon compounds that may have provided the chemical building blocks for abiogenesis. Summarizing, no other atom in our universe exists that can form the complex molecules required for self-replicating and evolving forms that are the basis of life. The enormous variety of life forms on Earth is the direct result of the unique chemistry of carbon-based molecules. No complex molecules based on such other elements as silicon or germanium that could be precursors of life have ever been found in outer space.

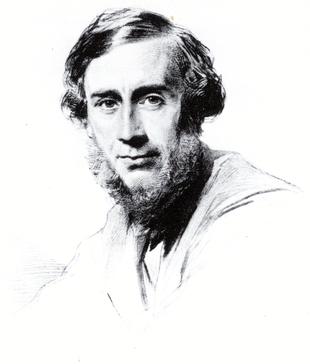

Ernst Mayr. Source: Goodreads, https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/19162.Ernst_W_Mayr.

In 1952, Stanley Miller and Harold Urey, at the University of Chicago, conducted an experiment attempting to simulate the conditions believed to be prevalent in the early Earth’s atmosphere. They used water, methane, ammonia and hydrogen, subjecting this mixture, in a sealed container, to repeated electrical discharges simulating atmospheric lightning discharges. This experiment produced several amino acids characteristic of living organisms suggesting that similar processes could have spawned early life forms. Subsequent experiments of this type, however, have not been able to generate the additional steps required to actually generate life. After nearly 70 years scientists have not succeeded in creating living matter as it appeared on our planet. I, for one, conclude that this failure is indicative of the improbability of abiogenesis and the creation of cellular life. The latest effort to elucidate the sequence of steps leading from a chemical world to a biological world in the primitive environment of the Earth is to be performed within the Planet Simulator announced in 2018 by researchers at McMaster University on behalf of the Origins Institute.

According to the researchers, preliminary tests did create proteins, not living matter but of definite significance on the path to true cellular life.

The alternative explanation for the appearance of life forms on Earth is panspermia, introduced above. It is the hypothesis that life exists throughout the universe, distributed by space dust, meteoroids, asteroids, comets, etc. Life on earth, following this hypothesis, was started by this process of seeding from space. This idea may have originated as far back as Anaxagoras in Ancient Greece and later picked up by Kelvin, von Helmholtz and Arrhenius. More recently this hypothesis has been advocated by the astronomers Fred Hoyle and Chandra Wickramasinghe. Panspermia is often criticized because it does not answer the question of the origin of life but merely transfers it to another celestial source.

Be it as it may, life appeared on Earth in the form of unicellular organisms as soon as it could and for a very long time afterwards continued in that primitive form. In fact, for about 1.8 billion years after that first appearance, life consisted only of simple prokaryotes, i.e., cells without an organized nucleus. A major advance occurred at the end of that initial period: the appearance of more complex life forms, the eukaryotes, the oxygenation of the atmosphere and photosynthesis. This was followed, another billion and a half years later by life in increasingly complex forms culminating about 550 million years ago with the altogether remarkable so-called Cambrian Explosion that

marked the sudden appearance of primitive animals from which all subsequent animals probably descend, followed by land plants some 75 million years later.

The figure below depicts a summary time line of the development of life on Earth showing the principal events that led to the very recent appearance of mankind. What I would like to emphasize in this context is that it took some 4 billion years for evolution to produce our technological level of intelligence. This represents almost

one third of the entire existence of our universe and this was required on what, in all appearances, is a most life-friendly planet.

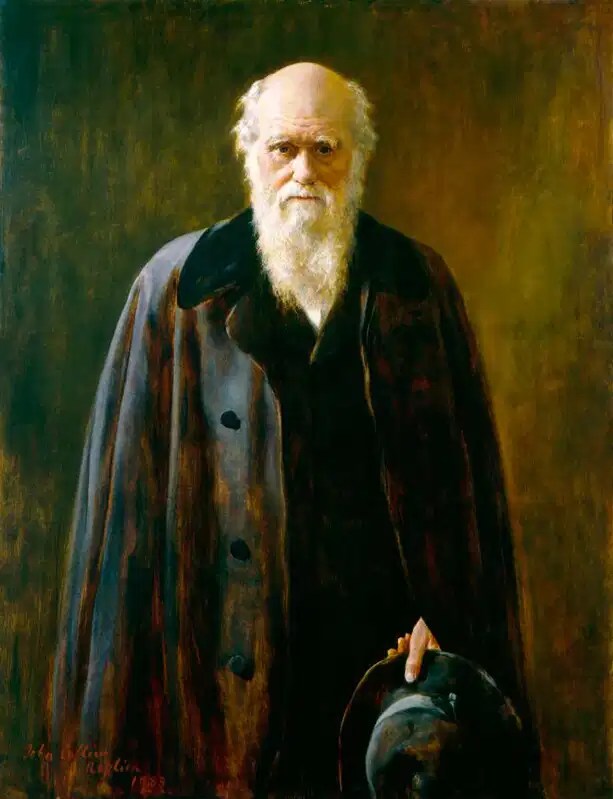

On the subject of evolution, I would like to refer to a statement by the renowned British evolutionary biologist, Richard Dawkins (born 1941) in his book Science in the Soul, Selected Writings of a Passionate Rationalist: “It is widely believed on statistical grounds that life has arisen many times all around the universe. However varied in detail alien forms of life may be, there will probably be certain principles that are fundamental to all life, everywhere. I suggest that prominent among these will be the principles of Darwinism. Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection is more than a local theory to account for the existence and form of life on Earth. It is probably the only theory that can adequately account for the phenomena that we associate with life”. I fully and emphatically agree with that postulate. Darwinian evolution is the only mechanism by which life can advance form simple unicellular forms to any complex forms. Certainly homo sapiens could never have appeared by fiat, and if advanced technological intelligence exists elsewhere in our universe, it will have been the product of Darwinian evolution as it was with our own species.

The Dinosaur’s Demise And The Monkey’s Journey

I will now treat the likelihood of humanity’s appearance on our planet in the context of life’s development as outlined above.

First of all, we have to look at the role of contingent events that occurred throughout those nearly 4 billion years of life on Earth. Perhaps the very first one to be considered is the compositional transformation of our atmosphere from a reducing type to one dominated by nitrogen and, crucially, oxygen. The appearance of this latter molecule in more than trace amounts was the result of of the inception of photosynthesis which, in turn, allowed the efficient use of solar energy by living organisms, eventually triggering the radical redirection of the Cambrian Explosion that completely reshaped life’s history on Earth spawning animals and subsequently plants that were to dominate ever since.

Several major upheavals followed during those momentous half billion years that have preceded us. Salient among those events were at least 5 major extinctions that reset the course of life’s development. We do not know the causes for these extinctions, except for the last one which, most probably, was produced by an asteroid impact. We do not know precisely the ultimate effect on life’s course on this planet by those earlier extinctions but it is probably safe to assume that our present biota would have been fundamentally different had those 4 initial extinctions not ensued, or occurred at different times in the past.

Be it as it may, it is generally accepted by the scientific community that the demise of the dinosaurs was caused mainly by the Chicxulub asteroid impact on the Yucatán coast 66 million years ago. How did this event affect life’s sequence leading to the appearance of Homo sapiens?

It is now believed that mammals appeared as far back as 200 million years not long after the first dinosaurs appeared. For some 130 million years mammals lived and barely evolved in the shadow of the dominant dinosaurs. It is believed that during that long interval mammals did not evolve beyond shrew-like animals having to hide, perhaps limited to nocturnal and underground life, from the formidable reptiles that surrounded them. Within less than a million years of the disappearance of the dinosaurs, however, the evolutionary process of the mammalian class virtually exploded. All the mammal groups we are familiar with developed during this period, whales, tigers, and…mankind. It does not require much imagination to reach the ineluctable conclusion that the demise of the dinosaurs opened the door to the evolutionary process that culminated in the appearance of our own species. If the dinosaurs would have continued their dominant existence, hominids, i.e., the precursors of homo sapiens, would never have appeared and consequently neither their technologically advanced descendants. Thus, we owe our existence to the tremendously destructive impact on the Earth of a 10-mile asteroid, 66 million years ago; our appearance was contingent on the chance collision between two celestial bodies.

The improbability that evolution would culminate in Homo sapiens should be understood in the context of the nature of evolution itself. A final crowning such as that of our species is far from foreordained. The path of evolution is characterized by multiple branchings governed by chance. After all, gene mutation is a random process that is followed by natural selection which is not a directed process but one aimed at improved adaptation to the environment. For about 4 billion years that process of natural selection did not choose to produce advanced technological intelligence. Here again, Ernst Mayr’s words on that subject in 1994: “Adaptations are favored by selection, such as eyes or bioluminescence, originate in evolution scores of times independently. High intelligence has originated only once, in human beings. I can think of only two possible reasons for this rarity. One is that high intelligence is not at all favored by natural selection, contrary to what we would expect. In fact, all the other kinds of living organisms get along fine without high intelligence. The other possible

reason for the rarity of intelligence is that it is extraordinarily difficult to acquire. Some grade of intelligence is found only among warm-blooded animals (birds and mammals), not surprisingly so because brains have extremely high energy requirements, But it is still a very big step from ‘some intelligence to ‘high intelligence’ “.

I will now cite a sequence of events that once more illustrates the improbability of mankind’s appearance even on our life-affirming planet.

To start out with let us look at Earth’s surface over the last 200 million years. The sectional world map above shows the sequence of continental drift driven changes until the present. We start with Pangaea, the super continent from which all present continents derive. About 130 million years ago, North America and Asia together broke off and South America and Africa formed another separate block. Sometime later, approximately 100 million years ago, South America and Africa began to separate creating the South Atlantic Ocean. At the time of the Cretaceous-Palogene boundary (previously known as the K-T boundary) marking the Chicxulub asteroid impact 66 million years ago, the separation between S. America and Africa had been completed and the South Atlantic Ocean widening was proceeding. Hence, until about 100 million years ago, the biota in what is now Africa and S. America were essentially the same, except for regional differences. Both of these future continents would have been populated by dinosaurs and those primitive “oppressed” mammals. In fact, very similar dinosaur fossils have been unearthed on the two sides of that S. Atlantic divide. So, we can safely state that had the split between S. America and Africa not occurred, evolution would have proceeded along similar paths on both continents. However, once that separation occurred, evolution followed very different paths on both continents. In the animal kingdom that concerns us here, on the African side of the Atlantic, very diverse species appeared. It is believed that primates came from Eurasia into Africa where they spawned a variety of species such as monkeys and, later, the great apes. Eventually Homo sapiens evolved from one of many branches of apes. In the meantime, what happened in South America? Having started with similar forms of life as in Eurasia and Africa, and once the dinosaurs disappeared, primates did not develop in that former continent, thus we have no indigenous South American monkeys, apes and Homo sapiens. But, wait a moment. There must be a mistake here. After all, there are lots of monkeys in South and Central America, scientists call them New World monkeys! Clarification follows.

Until the early 21st century, the origin of these New World monkeys was a bit of a mystery. No precursors of these monkeys had been found in the Americas. So, Where did they suddenly appear from? To the rescue comes Alan de Queiroz in 2014 with his book The Monkey’s Voyage: How Improbable Journeys Shaped The History Of Life, and here follows the unlikely story of the origin of New World monkeys.

It seems that about 45 million years ago a group of monkeys had taken residence on a large leafy tree on the Atlantic shore of West Africa. A violent storm uprooted the tree which fell into the water with its contingent of monkeys. The wind then drove the floating tree away from the coast and deep into the Atlantic. This ocean was not as wide at that time as it is now, thanks to continuing continental drift. Eventually, the little host of monkeys, presumably hungry and bedraggled, made land fall on the coast of what is now Brazil. They dispersed from there across the continent and their descendants evolved into the numerous species of monkeys throughout Central and South America that are familiar to us today.

The descendants of that motley group of African monkeys, however, never developed into apes and hominids as their cousins did in Africa. It is from this fact that I want to build the case for the improbability of mankind’s appearance. The same “prime material” of early shrew-like mammals eventually evolved into Homo on one side of the Atlantic divide whereas on the other, monkeys had to be “imported”. We can only deduce from this striking dichotomy that our appearance was anything but inevitable and that even under the most favorable of environments that our planet offers to the development of life, advanced technological intelligence is a totally improbable outcome. I believe that there are many more examples that support this conclusion, among them the multiplicity of evolutionary dead ends of the numerous hominid branches that preceded us in the last several million years.

Mostly Pretentious Science Fiction

At this point I would like to introduce some hypothetical scenarios proposed by various thinkers, writers and even astrophysicists of note on the subject of alien advanced intelligent life.

One of the more cited of these ideas was developed by the Soviet astrophysicist, Nicolai Kardashev in the 1960s. He not only assumed the reality of the existence of extraterrestrial civilizations but created a classification of these civilizations by the degree of their sophistication. He suggested three levels of advancement: Type I, similar to our own present level, Type II, capable of harnessing the entire energy of their own star, and Type III, a civilization capable of utilizing the energy output of an entire galaxy. Presumably, a Type III has taken over its galaxy obliterating competition from any other aliens in their galaxy.

Equally famous has become the hypothetical scheme postulated by the rather well known physicist Freeman Dyson who, as early as 1959 speculated that the more advanced of these alien civilizations could have rearranged their planetary system in a spherical shell surrounding its host star to optimize the collection of energy from that sun. As a result, such artificial planetary configuration shielding its star would emit preferentially in the infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum and could thus be identified. This planetary arrangement was to become known as a Dyson Sphere.

Others advocated interstellar manned travel at speeds approaching that of light in order to find alien civilizations and thus communicate with them. Fortunately, sanity seemed to prevail on that front embodied by authoritative contributors to the discussion such as the 1952 Physics Nobel Prize winner, Edward Purcell, who stated dismissively: “All this stuff about traveling around the universe in space suits – except for local exploration…. – belongs back where it came from, on the cereal box.”

At this time (2021), the fastest human spacecraft to date has been capable of traveling at 165,000 mph (265,000 km/h) with which we would require a mere 17,300 years to reach the closest exoplanet, Proxima Centauri b. A major technological breakthrough (at this time unforeseen) would be required to shorten this travel time significantly if a human crew is to undertake even such a minimal journey.

Further, in this context, we have to watch out for the crackpots such as the believers in alien UFOs, abductions, and past visitations such as those imagined by the likes of Erich von Däniken. Starting in the 1950s, numerous sightings of flying saucers, now morphed into Unidentified Flying Objects – UFOs – have been claimed to be of extraterrestrial origin proving that there are advanced aliens “out there” that are taking an interest in us. By far, however, most of these sightings have been identified as caused by anything but visiting aliens. It is most likely that all those observation were and are either caused by natural phenomena or by a host of instrumentation glitches.

I had my own full blown UFO-sighting “experience” when I was about 20 years old. I have included this happening in my autobiography. I will summarize it here. I was

walking on a street in Quito, Ecuador, where I lived at the time (mid-1950s), and I saw a man looking intently at the blue sky. He described to me sighting a flying saucer going a great speed and flashing light in various colors. After a short while I saw what had attracted his attention: it was the planet Venus which I knew could be seen during a clear day, for a few weeks, about every two years. When I tried to enlighten the observer he dismissed me contemptuously. Then, word had gotten around town and there were hundreds of people gathered on the main square and when I tried again to convince another gentleman that this was Venus he dismissed it walking away from me. This incident did little to convince me about the existence of alien UFOs but it certainly taught me a lesson about human gullibility. The idea that after traveling untold trillions of miles through space aliens would be buzzing around the Earth startling a few hapless believers in the countryside stretches my credulity. Recently (April 2020), some UFO videos were declassified by the Pentagon on which Katie Mack, an astrophysicist, commented: “I don’t think it’s completely impossible that hyper-advanced aliens could come to visit us on Earth – being careful for some reason to first evade every sky-monitoring system we have, and leaving no observable trace other than the confusion of a handful of Navy pilots”.

The Anthropic Principle

It is, in my opinion, a pretentious and tautological “principle” that, essentially states either that our universe is as it is because otherwise we would not be here to observe it, or that the very presence of intelligent life constrains our universe to be as it is. At its core, the anthropic principle is based on the assumption that the fundamental physical constants of the universe in which we live must be “fine tuned” to permit us to exist.

These constants – such as the fine structure constant, the charge of the electron, the rest mass of the proton, the speed of light, the gravitational constant, etc. – are such that they are compatible with our existence. The counter-argument, as expressed by Steven Jay Gould, states that the reverse is true, i.e., that evolution has shaped our life to adapt to the conditions existing in the universe.

The anthropic principle has been invoked to both support the uniqueness of humans on earth and the multiplicity of advanced intelligent civilizations throughout our universe.

This debate, in my view, belongs to the realm of philosophy rather than physics, and I will not dwell on this principle any further. Ultimately, if we did not exist we could not ponder about the possibility of our existence.

A Galactic View

I will now attempt to look at the habitability and the likelihood of the existence of advanced technologically communicating civilizations within our Milky Way galaxy.

It appears that certain regions of our galaxy may not be compatible with life and that our particular neighborhood may be rather more friendly to life.

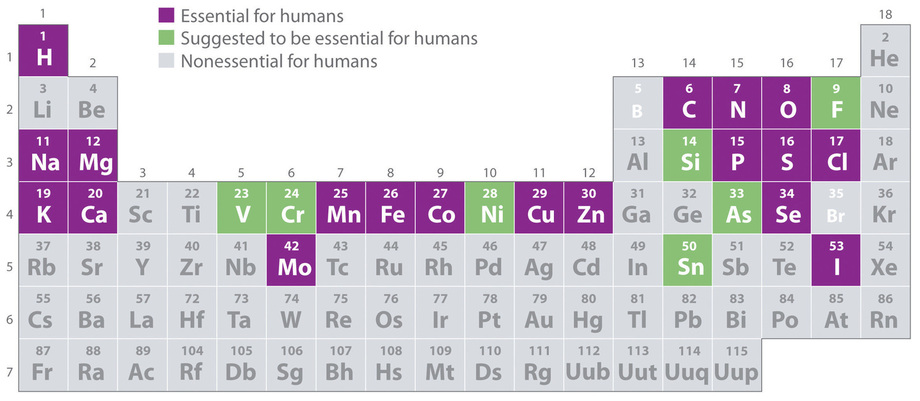

In general, not only within our galaxy but throughout our universe, we have to consider what is called metallicity. Stars, their accompanying planets and their moons are characterized by that parameter. It is a measure of the presence and proportion of elements heavier than the primordial hydrogen and helium. Metallicity is an astrophysicist’s misnomer since it has nothing to do with metals but with all the elements of the periodic table beyond the primordial ones which were the initial building blocks of our universe formed shortly after the Big Bang.

Metallicity is an important parameter on which life as we know it depends quite crucially. Elements such as carbon, oxygen, magnesium, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, iron, etc. are essential ingredients of life. Nucleosynthesis, the process by which these elements are created, occurs as stars near the end of their existence. The heavier elements are actually produced when a star explodes as a supernova. It is surprising to reflect on the fact that human beings are the product of the violent demise that characterizes the final phases of larger mass stars. Our bodies are star dust.

The periodic table shown below has been modified to highlight those elements that are either essential to human life or are thought to be so. The remaining elements are not deemed to be required for our chemical make up.

So, high metallicity is what characterizes more recently formed stars and their planetary

systems. Our Solar System is believed to be a third generation system in that at least two generations of stars preceded it since the Big Bang, each preceding stellar generation

contributed to the build up of the metallicity required for our existence.

Now, within our Milky Way galaxy there are regions where the stars – and presumably their cohort of planets – exhibit higher metallicity thus being more compatible with life as we know it. More general, however, is the concept of galactic habitable zone which is the region of a galaxy in which life is more likely to develop. The criteria contributing to the habitability of planets within a galaxy are rather complex and their discussion is beyond the scope of this essay. These criteria include — but are not limited to — metallicity, separation from supernova prone regions, presence of elements required to form rocky planets as well as magnetic cores, presence of sufficient radioisotopes of long half-lives to ensure extended internal planetary heating, and active tectonic dynamics believed to be required for the development of life. Considering all factors thought to contribute to galactic habitability, the Sun and its planets are advantageously placed within the galaxy, outside a spiral arm and orbiting the galactic center in what is called the corotation circle where the stars move at the same speed as the spiral arms. All these factors need to be considered as further elements of the Rare Earth version of the Drake equation, i.e., these are further qualifiers that constrain the probability of advanced intelligence within our galaxy.

It is interesting to reflect on the location of our Solar System within the Milky Way galaxy. We are about mid-way between the center of the galaxy and its periphery, approximately 26,000 light years from the center, as shown in the subsequent computer generated image of the galaxy, as viewed perpendicularly from its plane. This virtual image also shows the location of the principal arms of the spiral shape of our galaxy. The central region of the Milky Way galaxy including the highly dense bar, within a radius of about 10,000 light years, consists predominantly of older stars. These stars are expected to be of lower metallicity and therefore less likely to harbor life. The spiral arms are principally of younger age and are thus considered to be potentially habitable. As mentioned before, our Solar System is located near a spiral arm, the Orion arm, and rotates once around the galactic center every 250 million years.

Another factor that needs to be considered in the context of galactic habitability is the role played by the type of star around which planets revolve. In the case of our Solar System, the Sun is classified as a G dwarf, with a surface temperature of almost 6,000K. Several stellar characteristics appear to be critical to the habitability of any exoplanet orbiting within the Goldilocks zone wherein surface liquid water can exist. Among these properties we can mention:

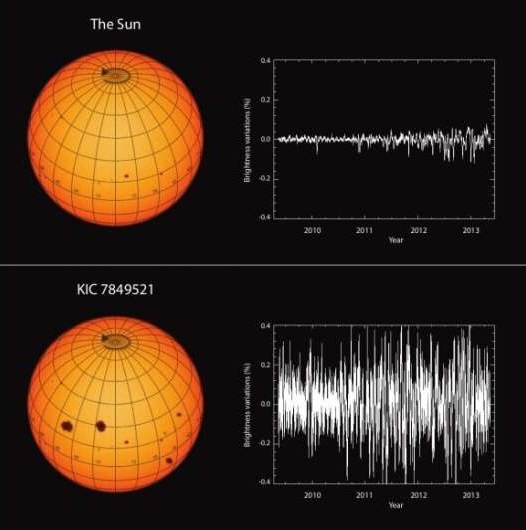

- a magnetically quiet star may well be critically important to the development of life, and the Sun appears to uniquely satisfy that criterion. Magnetic activity of a star correlates with brightness variations. The figure further on compares the Sun’s brightness fluctuations with those of a similar and more typical type of star (KIC7849521) over a period about 4 years. The Sun’s luminosity is remarkably quiescent which would foster life in all its forms.

- Stars more massive than 1.5 times that of the Sun age too rapidly to allow for the evolution of advanced life. After all, our Sun formed 4.5 billion years ago which was about the time required for the appearance of mankind. More massive stars burn hotter and end their normal life violently as a supernova in a much shorter time. For example, a star with an initial mass 3 times that of the Sun has a life expectancy of only 200 million years as compared to that of of the Sun of about 10 billion years.

- On the other hand, the vast majority of stars in the Milky Way galaxy are older, type M red dwarfs which are much smaller and colder than our Sun. As a consequence, their habitable zone is much closer to the star which, in turn, results in several effects that are unfriendly to life: 1) their planets tend to be tidally locked which means they always face the same hemisphere towards their star, similar to our Mercury, and would tend to lack axial tilt, and 2) these closer planets receive a more intensive particle radiational bombardment tending to strip their atmospheres and impede life. Furthermore, M-type stars, because of their greater age, tend to exhibit lower metallicity.