AND OTHER TIDBITS

2020

The Early Years in Quito

My professional career followed unforeseen paths that to some extent mirror my family’s peripatetic wanderings. Although, initially, it appeared as if I were to proceed along a predictable direction, perhaps following my father’s electrical engineering footsteps, my inclination towards more scientific pursuits deviated me from that path.

Notwithstanding my academic engineering education my true calling was to be science and, more specifically, physics. Engineering eventually became for me a means to an end but not an objective per se. I could, at times, be quite ingenious in solving engineering challenges, but my curiosity for the truly original and innovative was directed principally towards more fundamental scientific principles and the pursuit of knowledge and understanding of nature. Nevertheless, my most fruitful endeavors were to straddle the fields of engineering and physics.

I believe that I inherited – either genetically or by example (or both) – from my father an ability to solve practical problems, although he was definitely the better engineer whereas I tended to explore farther afield, starting with my early and then persistent interest in astronomy and astrophysics. My initial scientific interests, however, were not restricted to such lofty directions. The behavior of yellow poppy flowers in our garden in Quito arose my curiosity. They were wide open during sunny days and closed in tight little rolls in bad weather and at night. I decided to perform a simple experiment to elucidate whether the poppies responded to changes in air temperature or to ambient light. I covered the plant with a cardboard box when the sun was shining and the flowers were wide open. If light was the driving cause, covering the flowers would elicit their closure. After several tests I came to conclusion that neither temperature nor light were sole causes, but a combination of the two stimuli.

Similarly, as I have described in the joint – Erich’s and mine – autobiographical notes[1], I needed to understand the striking discrepancy between apparent and actual size of planets when viewed through a telescope. I also learned about psycho-acoustics through experimentation with recording and re-recording sound in enclosed environments. This need to comprehend the world and its phenomena was to accompany me for the rest of my life, and has been an effective shield against any inroads by irrational or metaphysical explanations while providing me, repeatedly, with the true exhilaration and pleasure in finding rational and scientifically robust causes for observed phenomena. This rational approach has also led me to more transcendental conclusions that, I found to great personal satisfaction, later have become increasingly part of the accepted scientific discourse. Case in point, is the presently growing acceptance of the possibility of the multiverse about which I thought some 15 years before I came across any mention of this concept. I developed this idea based on my conviction that our view of the universe – both in the realm of the ultra-small as well as the ultra-large – has tended to be hopelessly provincial, i.e., pre-Copernican. As is well known, we tend to place ourselves in the geometric mean of the dimensions of the known universe thus restricting its extent in both realms. Historically, this constriction has been relaxed gradually as knowledge has extended boundaries in both directions. But, I believed and continue to do so that there are no limits in either realm and that the “total universe” is one of infinite hierarchies, although it is quite conceivable that there may be insurmountable barriers for an unbounded discovery of such meta-hierarchies. But, I am jumping ahead. I shall revisit these lofty lucubrations in due course.

My professional career has followed two parallel paths: That of device inventor – the “gadgeteer” – and that of writer and explainer. The two facets often converged and complemented each other. Another aspect worthy of mention is that I frequently succeeded in being perceived by my peers as a pacesetter and expert in whatever area I pursued. This latter tendency was probably enhanced by my – sometimes reckless – self-assuredness, my ability for articulate synthesizing of technical and scientific concepts, and a keen sense of observation. I always relished the challenge of technical problem solving to which I brought the mind of a generalist aware of far flung possibilities.

More than once, however, I started a project with a rather meager knowledge of the fundamentals of the problem at hand, but managed very often to rapidly fill in the gaps of my understanding to the point where I felt to be in a position superior to that of my peers.

But let me return to the main line of this quasi-narrative.

Perhaps the two most original techno-scientific pursuits of my early days in Quito were the construction of an adjustable star chart for latitude zero, and the pioneering measurement of electromagnetic crustal conductivity in the region around Quito.

My family in Paris – the Fourestiers – had sent me, in addition to a nice brass telescope, an adjustable star chart – for the latitude of Paris – that was not too useful in Quito, 15 miles from the Equator. I found in an old astronomy book large fold out charts of the stars of the northern and southern hemispheres. I pasted those two circular charts on the two sides of a cardboard disk (about 24 in. in diameter) with a central shaft mounted on a wooden pedestal that also covered the lower half of each of the sides of the disk. It was thus possible to view the two halves of the hemisphere visible in Quito at any given date and time by rotating the disk. It worked beautifully. I should have patented the device which I eventually abandoned when finally leaving Quito for the U.S. in 1959.

The determination of the electromagnetic soil conductivity was performed as part of my engineering thesis work at the Escuela Politécnica. I have described that work in my autobiographical notes. I believe that the execution of this project was rather ingenious in that I built an electromagnetic field strength meter by reverse engineering an existing commercial instrument which I was able to borrow for a short time, then combining it with the car radio to measure the relative field strength of an existing AM broadcast station as a function of distance in various radial directions in order to arrive at the value of the average electromagnetic soil conductivity in the region around Quito, a parameter required for the design of the national radio broadcast station for Ecuador. This was the subject of my thesis with which I graduated with summa cum laude honors.

During my last years in Quito I actively assisted my father, Erich, in the repair of radios and sound reproduction equipment. It gave me the opportunity to become thoroughly familiar with such equipment and with methods of identifying the causes and remedies of most its failures. Although I found such investigative work quite rewarding, I would not have considered such endeavors as sufficiently fulfilling for a future career.

At DEL Electronics Corp.

Jumping ahead, after my less-than-glorious departure from Columbia University in New York, I gained employment at a small company – DEL Electronics in Mt. Vernon, N.Y. – through the friendship of Victor Landau, my father-in-law, with the president of that firm, Mr. Joseph Delcau, whose wife he had known from old Romania. Thus, my first full time job was obtained through convenient connections.

I started at DEL in June 1960, after returning from a seven-week honeymoon trip to Ecuador and Europe. I was assigned to work on the design of regulated high voltage power supplies under a boisterous Italo-American senior engineer. It was a somewhat less than thrilling job about which I have little or no recollection. After a few weeks on that assignment, however, I became aware of a very different activity that was taking place in an adjacent laboratory area, about which I became increasingly interested and curious.

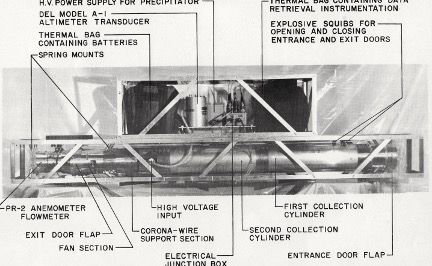

After a few conversations with the leader of that next-door project, Sam Cravitt, who I impressed with my questions and observations, proposed that I join the project as a junior research engineer, since he was in need of an experimentalist at that time. I was thoroughly delighted to abandon the hum-drum electronic circuit design work and engage in applied research and development in – of all things – air sampling at stratospheric altitudes in order to capture microscopic debris particles resulting from atmospheric nuclear test explosions. This project was supported by a contract from the then named U.S. Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) (now Nuclear Regulatory Commission) to gain knowledge about the design of Soviet nuclear weapons. DEL Electronics had managed to obtain that contract because one of the company’s principals, Mr. Di Giovanni (DiGi), had been a researcher at the AEC and had proposed to develop a balloon-borne air sampling system based on electrostatic precipitation of particles, a method that incorporates the use of high voltage whose generation was to be the main business of the company.

I thus became – or rather fell into becoming – an aerosol physicist. I had never even heard of the technical term “aerosol” before starting on that project but became rapidly acquainted with that field in subsequent months, and eventually became a specialist in esoteric areas of that discipline in the years to follow.

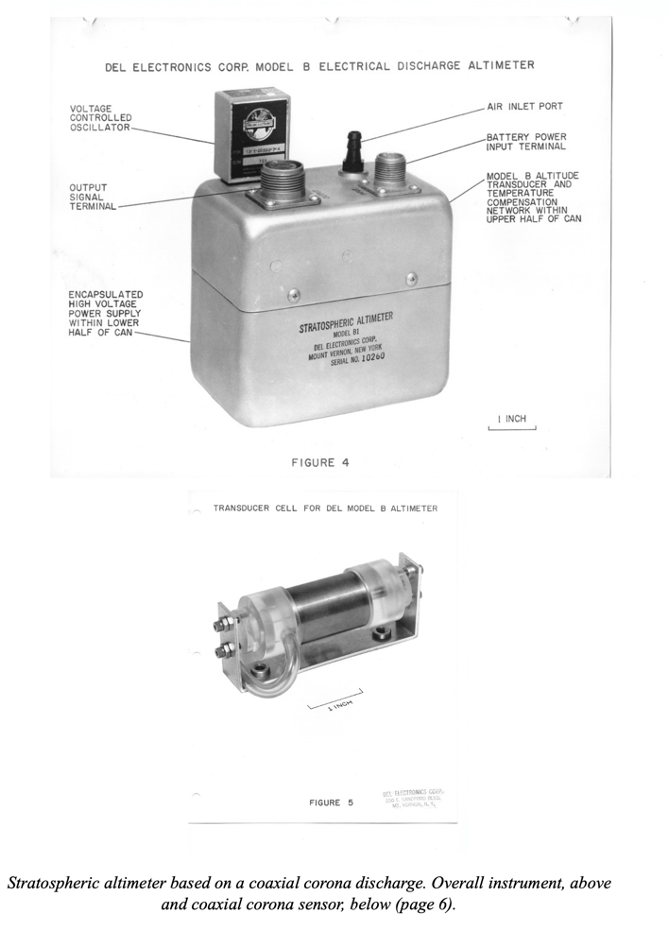

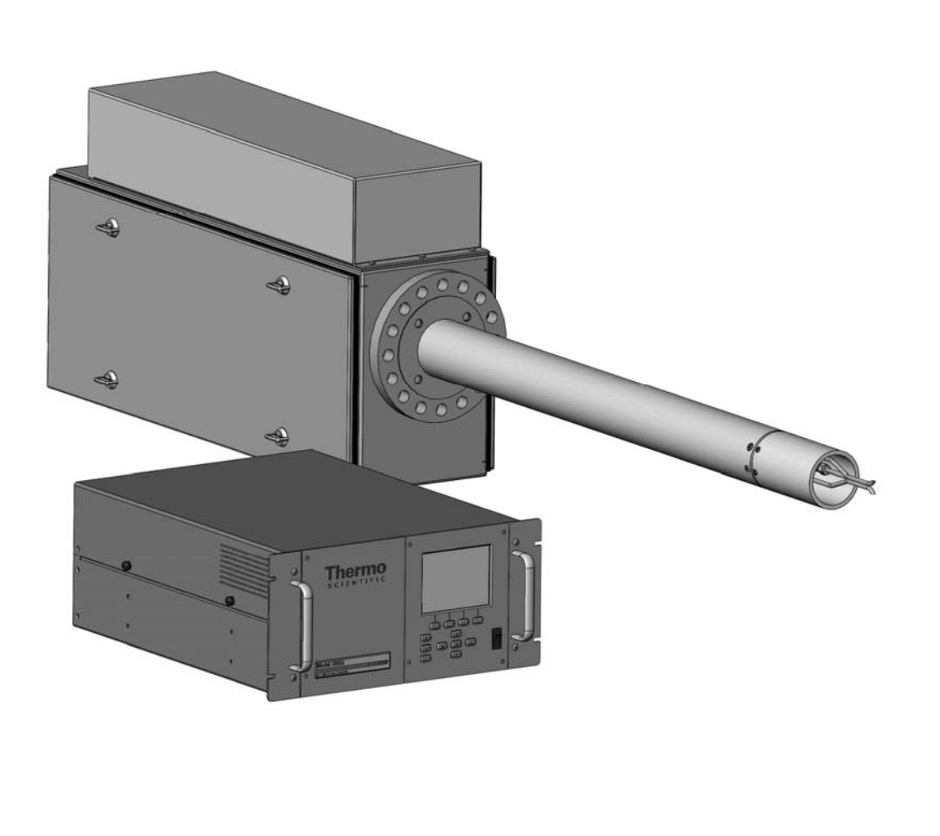

My initial assignments were centered on ascertaining the particle collection characteristics of a coaxial (concentric) electrostatic precipitator consisting, in essence, of an axial fine wire and a metal cylinder surrounding it, applying a high voltage (several thousand volts) between the wire and the cylinder, and running rarefied air – to simulate high altitude conditions – with suspended microscopic particles through the wire-cylinder precipitator (see figure below). The particles were collected on the inside surface of the cylinder because they were being charged electrically by the ionized air molecules generated by the corona discharge surrounding the axial wire.

I needed to find out the collection efficiency of the system as a function of operating conditions (value of high voltage and induced corona current, air flow rate, simulated altitude), size of the particles, and precipitator dimensions. All this, in order to optimize the design and operation of the collection system.

I used membrane filters to collect the particles at the entrance and at the exit of the precipitator. The test particles were of a fluorescent material dissolved in purified water, and aerosolized (the technical term for “nebulized”) by means of a special fine spray generator. After each test run which lasted typically one hour, the filters were washed in distilled water and the fluorescence of this liquid was then measured in a fluorimeter in order to determine the amount of particles collected on these filters. The ratio between the amounts collected upstream and downstream of the precipitator provided a measure of its efficiency for each of the different operating and dimensional conditions that I used.

There was copious data gathering, and while the tests were running, I read assiduously about aerosol physics, and developed equations that would help in evaluating the experimental results that I was obtaining.

All the tests were performed inside a cylindrical Lucite chamber, about one foot in diameter, attached to a large vacuum pump that maintained the low pressure in the precipitator that simulated altitudes ranging from 100,000 to 150,000 feet, the height to which special very large research balloons could ascend.

This work involved many areas with which I had been previously unacquainted – or barely so: generation of aerosols (airborne particles) of variable size, electric charge neutralization of particles by means of bipolar corona discharge, sampling by means of membrane filters, particle impaction phenomena, unipolar electric charging of particles in a coaxial corona discharge in rarefied air (about which no previous work had ever been done), collection of these charged particles by precipitation in rarefied air (also previously largely unknown), reduced pressure corona discharge, rarefied air flow dynamics and measurement, fluorometry, etc., etc. This was largely a virgin field for me (as for almost anyone). I thus developed a unique expertise in certain fringe areas of aerosol physics and gaseous electrical discharges. Eventually, I extended this work to electron microscopy for which I developed special miniature electrostatic precipitators for direct particle collection on electron microscope grids, the little circular substrates on which samples need to be deposited for such microscopy. DEL Electronics acquired a Phillips electron microscope with AEC funding. This permitted us to determine exactly the size of the particles I was generating for the electrostatic precipitator tests.

§

Soon, I had to broaden the scope of the project. Two related challenges arose: one, was to be able to measure accurately (and inexpensively) the altitude of the balloon that was to carry the equipment to stratospheric heights. The other, how to measure the sampling air flow rate driven by a special coaxial fan through the precipitator. Aneroid altimeters (those based on pressure sensing) did not work reliably above about 90,000 feet, and there were no flow meters capable of measuring flows of the order of 100 cubic feet per minute under such rarefied air conditions. I had observed that the required high voltage and the resulting corona current in the precipitator were very much dependent on the air density, i.e., the altitude. I thus proceeded to develop a miniature version of the precipitator – a small wire-cylinder sensor – specifically designed such that the corona current through the device would be related to altitude and could be recorded and transmitted down to a ground station by radio telemetry. The device was eventually flown successfully on several high altitude balloon flights which I will describe further on.

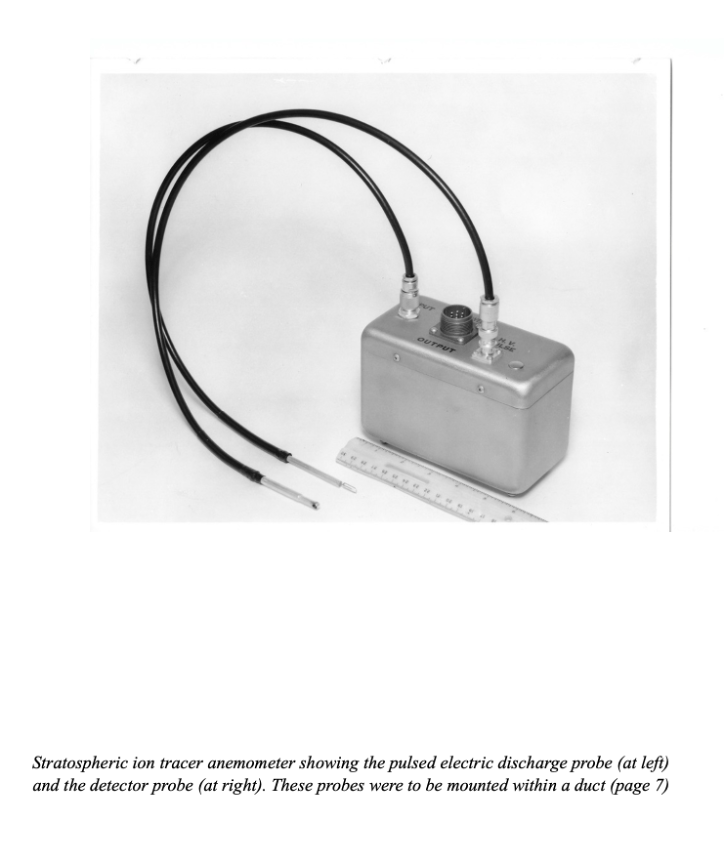

My solution to the second challenge, the measurement of rarified air flow, was to develop an ion tracer anemometer (air velocity sensor). The idea was to produce a brief electric discharge within the air stream to be measured and picking up the resulting ion burst downstream at a fixed distance. The time between discharge and downstream detection provides a measure of the air velocity between the discharge and detection points.

The story of the development of this ion tracer anemometer is an instructive cautionary tale worthy of detailed description.

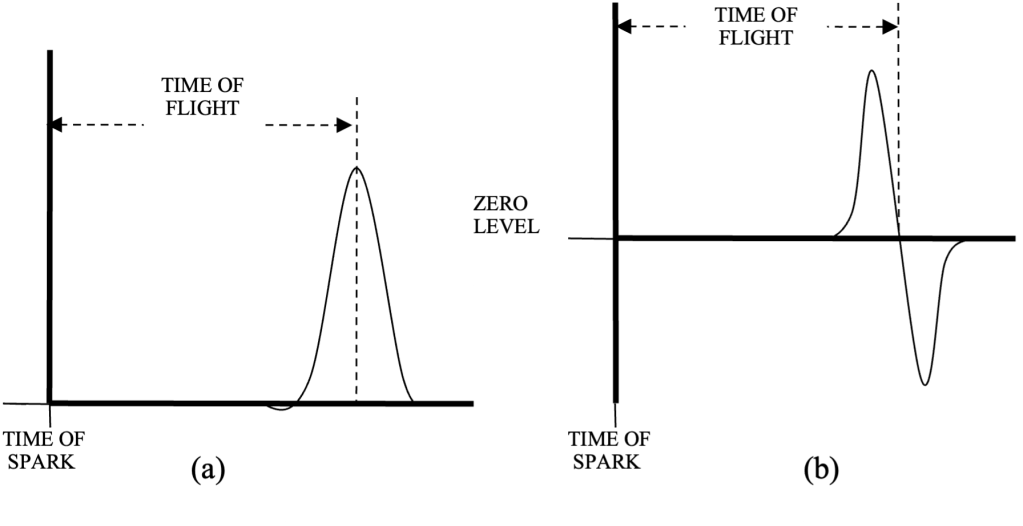

I proceeded to assemble an experimental test system of this device consisting, in essence, of a small spark gap to be inserted in the stream, a pulsed high voltage power supply to be connected to that spark gap, a short length of wire placed a few inches from the spark gap along the direction of air flow and connected to an electronic signal amplifier which, in turn, was connected to an oscilloscope. The idea was that ions injected into the air stream by the electric discharge would then be detected somehow by the wire (which was expected to act as an antenna) and displayed on the oscilloscope screen a short time later (milliseconds after the discharge) due to the air motion. I completed the set up within the simulated altitude test chamber and, Eureka! I was able to see the signal (a Gaussian shaped pulse) whose delay (time-of-flight in technical discourse – see figure below) was, indeed dependent on the air velocity. After a few days of further testing with what was a hastily assembled test system, we contacted the contract monitoring official in Washington to give him the good news about this successful development upon which he decided to pay us an immediate visit to witness a demonstration of this novel rarified air flow sensor.

In preparation of the official’s visit the next day, I instructed my technician to clean up the experimental set up which was a bit of a rat’s nest with twisted wire connections and bits of tape. He did so late in the afternoon on the day preceding the scheduled demonstration. The next morning, prior to the arrival of the contract monitor official, we turned on the system to have it in full readiness. To our surprise and shock, it did not work. No signal could be detected by the usual appearance of the pulse on the oscilloscope screen. Frantically, we checked all connections, the spark generator, the electronic signal amplifier, etc. Everything seemed in perfect working order but no detection signal could be discerned.

The official arrived and I had to spend the next couple of hours trying to explain away our utter failure to demonstrate the – to him now questionable – breakthrough in high altitude flow sensing. I was thoroughly mortified and puzzled, and could not wait to see the disappointed contract monitor out the door to proceed to attack the problem and solve the mystery of the dysfunctional ion tracer anemometer.

I eventually found the answer by not asking myself why the experimental system did not function but by posing the reverse question: Why had it worked before we “cleaned it up”? I needed to go back to basics. I sat down at my desk and pondered about the ion cloud detection process. The signal observed with the original set up was a bell-shaped unipolar pulse, as shown on the left side of the figure below (view a). If the signal were produced by induction by the passing cloud of ions, I reasoned, the signal should appear as a double pulse, one half going up and the other going in the opposite polarity, as depicted on the right side of the figure below (view b). I tested this by rubbing an acrylic rod (thus charging it with ions of one polarity) and waving it past the small detection wire of the ion anemometer and the resulting signal indeed conformed with my prediction. On further thought I concluded that the spark discharge produced a bipolar ion cloud which would fail to induce any net signal as it passed by the detection wire. The observed signal – when the device worked – had to be produced by collection of ions of one polarity by the detection wire. This, in turn could only occur if that wire was at some potential (voltage) with respect to the surrounding metal tube. Using a battery of a few volts in series with the detection wire I tested the system and…Eureka! It worked, giving me the nice signal (view a) that I had obtained originally before we “cleaned up” the experimental set up.

So, Why had the sloppy test set up worked and not the “cleaned up” one? I came to the conclusion that the “imperfect” connections with dissimilar metals (copper, brass, etc.) produced sufficient contact potential to ensure the observed collection of ions of a single polarity. Once all connections were soldered (tinned) those contact potentials disappeared and we were unable to demonstrate the device to the disappointed official.

I derived a crucial lesson from this experience. If an experiment, a device, a system under development works and you don’t know exactly why, do not proceed without elucidating the mechanism, the process that makes it work. Otherwise you can expect unpleasant surprises and unforeseen problems, if not total failure at some stage of the effort.

Eventually, we designed a successful compact instrument which was incorporated in the particle collection system and flown and operated at stratospheric heights tele-metering the information down to the ground. This final version of the ion tracer anemometer operated as a closed loop device wherein each detection pulse triggered the next spark discharge thus producing a continuous sequence of signals whose frequency was directly proportional to the air velocity through the particle collection system.

♣

More and more, Sam Cravitt, the man in charge of this overall project disengaged himself from it as he saw that he could rely on me to carry on with the development work. He got involved with another project related to his prior experience in infrared detection for which he frequently called on me to provide him with support and to act as a sounding board whenever he ran into difficulties. As the high altitude particle collection project progressed I was given additional support by a rather eclectic and varied cast of characters, engineers and physicists hired by DEL Electronics who either worked for or with me. I recall, among others, Andrew Foldes, an affable Hungarian émigré with a degree in mechanical engineering, various laboratory technicians, and Joe Pignataro, an able junior electronics engineer. Two individuals stand out because of their idiosyncratic behavior. One of these was the physicist Klaus Weber, a German import who was, to best describe him, a cross between Casanova and a storm-trooper. He was grating, opinionated, and thoroughly obsessed about his purported exploits as a lover of innumerable women. In keeping with this obsession he attended every performance of Mozart’s Don Giovanni that he possibly could and identified with that character to a ridiculous degree. He was militantly anti-Catholic and during a flight to Minnesota as part of a project field trip he nearly went berserk when witnessing a woman passenger who found it necessary to allay her fear of flying by constantly fondling her rosary beads.

And then there was Bill Harris, a respected senior aerosol specialist, who had been hired to provide his expertise to the stratospheric particle project. He must have been in his early sixties and promptly wanted to impose his opinions on the work I was performing. Very quickly I found that these opinions were of questionable scientific solidity and I resisted him with tooth and nail. It became a very tense situation. His desk was adjacent to mine and on one occasion, as we worked side-by-side, he chose to place his feet on my desk – the soles of his shoes were a mere inches from my face. Finally, I took a deep breath and peremptorily requested that he remove himself from my desk. He did so but only after chastising me with an exhortation about the “American way” which I obviously was ignorant of and needed to learn about. His behavior became more and more belligerent towards me in the days to follow and made me quite uncomfortable to the point that I decided to take my grievance to the company management. I simply said that they had to choose between Bill Harris and me. It was a gamble, since he was a senior researcher, respected in his field and I was still a junior engineer/scientist. Two days later, he was dismissed, and I felt victorious and vindicated. Six months later Bill Harris died of a particularly virulent form of a neurological disorder making me feel quite contrite about my combative attitude towards him and my lack of recognition of any pathology in his behavior. This, I could, of course, attribute to the fact that I had no baseline reference of his “normal” past against which to compare his later peculiarities.

There were the three principals and founders of the company: Joseph Delcau the president (my father-in-law’s friend from Rumania), Hugo Di Giovanni (“DiGi”, the ex-Atomic Energy Commission researcher), and Dr. Raymond Kaufman. The former two were engineers and the latter a physicist. The only one who took any interest in the stratospheric particle work was DiGi. Delcau once made an appearance at the laboratory and his only comment pertained to the color of the wall paint. Dr. Kaufman had, in all appearance, lost any interest in physics and had become the financial officer of the company.

There not being any eating establishments in the vicinity of the DEL, we all brought our lunches to work. I usually had a sandwich prepared by Evelyn. We placed our respective brown bags in a communal refrigerator until consumption time. One day, as usual, I took the bag at lunchtime, ate the egg salad sandwich in it, and sat down to read. Soon after, one of the young electronic engineers approached me and timidly inquired whether I had eaten his egg-salad sandwich. He then informed me that he could not eat the remaining ham sandwich I had brought. His was kosher. He fasted that day until his return home in the evening. I was mortified and thereafter clearly marked my brown bag to preclude further infringements on the dietary constraints of some of my fellow engineers.

On the matter of other engineers at DEL, I discovered, to my surprise, that most of them were remarkably conservative, if not truly reactionary, in their social and political views including wholehearted support of the ongoing U.S. military involvement in Vietnam. I somehow expected that the engineering education would have resulted in a broader outlook and a more intellectual attitude, but that was obviously not the case at least within the cohort that surrounded me. I had frequent verbal jousts with several of these professionals with whom I thoroughly disagreed on the subject of Vietnam about which I had rather strong opinions. Also, surprisingly, there were two electronics engineers who lived in New Jersey and were willing to motor for 2½ hours each way to and from work every day, a full 5 hours on the road 5 times a week!

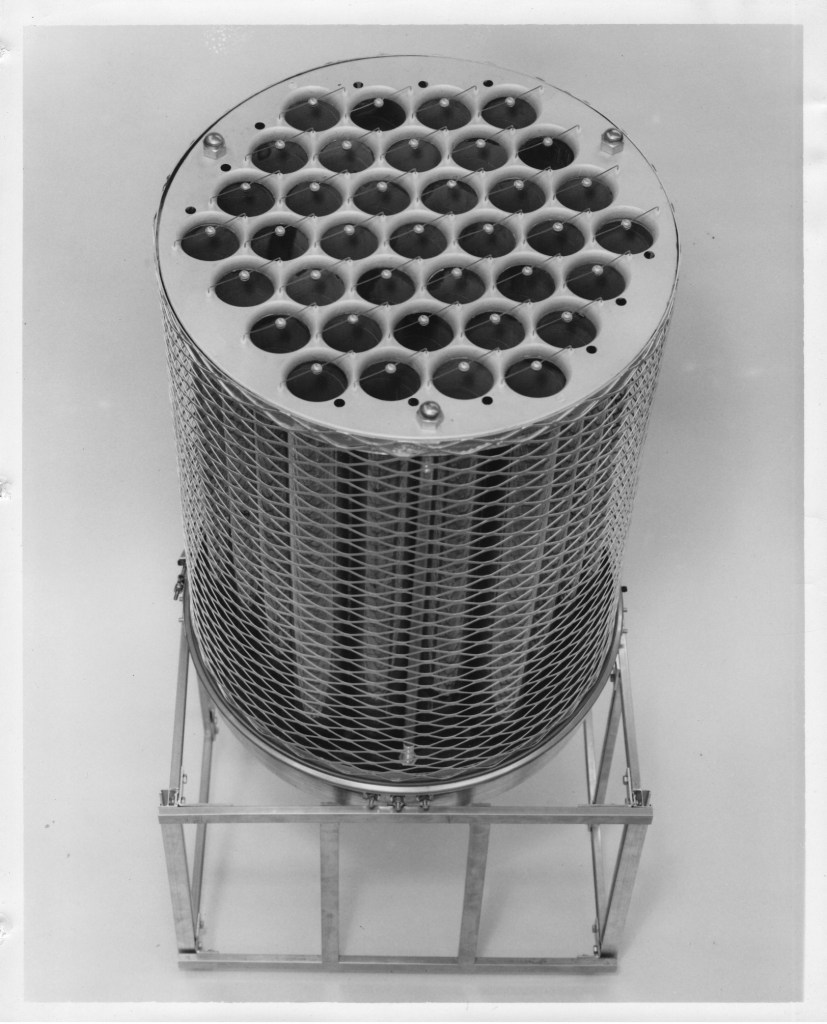

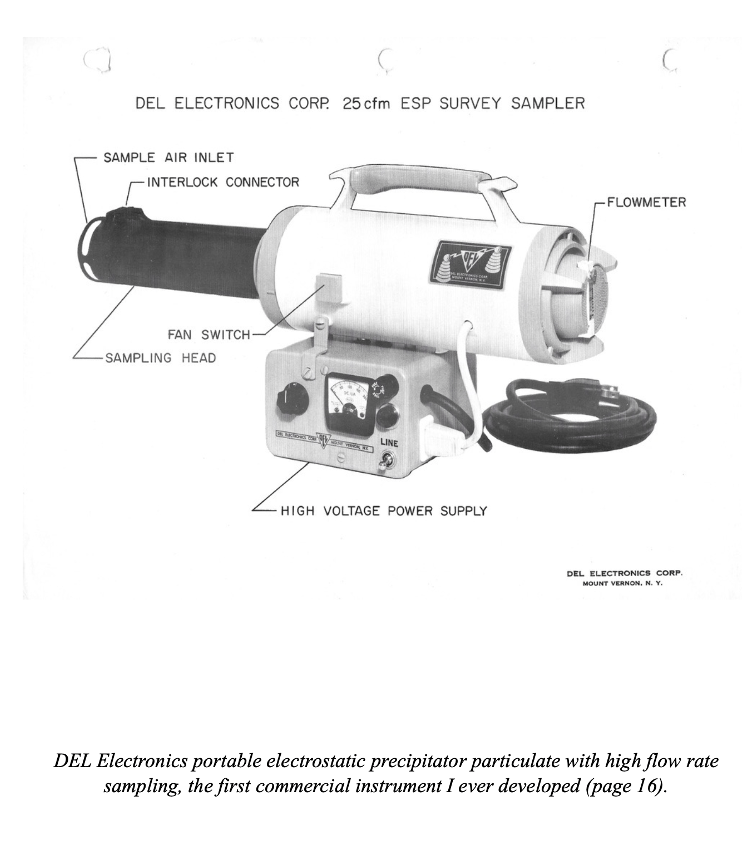

Two years after I started at DEL, in 1962, I was joined by Mort Lippmann. He had, at the time, a Masters degree from Harvard and was bright, imaginative and astute as well as a highly practical researcher with substantial knowledge about aerosols. He had concentrated his interest in the respiratory effects of airborne particulate matter and was to acquire in later years a worldwide renown in that field. We worked very well together – Mort had a good background in chemical engineering and in aerosol sampling which combined well with my experience in electrical gas discharges and physics at large. He stayed at DEL for about two years during which we collaborated in the design and development of a large second generation stratospheric electrostatic precipitator consisting of 37 parallel cylinders and the development of a portable industrial hygiene sampler based on electrostatic precipitation (see descriptions further on). Mort and I became good friends and we continued to be so ever since with the inclusion of our respective families. Evelyn and I attended Mort’s and Janet’s 50th wedding anniversary in November of 2006, 44 years later. After Mort left DEL in 1964 he went to get a PhD in biophysics at New York University where he was to remain for the rest of his professional life. Two years later, when I was considering to leave DEL, Mort arranged for me to be interviewed for a similar biophysics internship at NYU’s Sterling Forrest facility in northern Westchester where he worked. I will revisit this matter later on.

Before Mort left DEL, Sam Cravitt departed and rejoined the company at which he had worked previously, Farrand Optical. His replacement as project director was Dr. Leonard Solon[2] who came from the New York office of the Atomic Energy Commission. He was a radiation physicist, intelligent and of very pleasant demeanor. He was better at theory than practice, but we got along very well as we complemented each other.

♣

The first version of the stratospheric electrostatic precipitator, consisting of one 6-ft long tube (6-in diameter) was designed and fabricated with all its ancillary components (high voltage power supply, control box, etc.). It was transported to Minnesota and I traveled there to participate in its balloon launching. The balloon was fabricated by General Mills, the cereal company. They had a special group involved in these projects for the AEC. Later on that group was taken over by Litton. Now, whenever I happen to pour a bowl of Cherrios cereal I have to think back to that unlikely General Mills connection.

The balloon launching took place from a deserted airport west of Minneapolis. The electrostatic precipitator was suspended with springs within a protective aluminum frame to which the rest of the equipment was attached. This entire package was suspended from the Mylar balloon filled with helium just prior to its release. The balloon was inflated only to a small fraction of its final stratospheric volume. On the ground, it resembled a long, floppy sock. Gradual expansion, as it ascended through the thinning atmosphere, then resulted in its near-spherical shape with a diameter of about 250 feet, once it reached its “float” altitude somewhere between 110,000 and 120,000 feet, about three times higher than the cruising altitude of a typical jet airliner.

The launch procedure required critical timing. The payload was mounted to a flat-bed truck, and upon release of the balloon from the ground, the truck had to move rapidly under the rising balloon and release the payload – by an explosive bolt – at the moment the balloon was directly overhead. If the release occurred before the balloon was vertical, the payload could bounce around the ground or on the truck. If too late, the tethers could rip. Launches were performed usually before sunrise, a time of minimal winds.

The typical sampling flight sequence was as follows. It took about two to three hours for the balloon to reach its “float” altitude, the altitude at which the overall weight of the system (including all components) equals the weight of the displaced air (with due thanks to Archimedes). At lower altitudes, the weight of the displaced air is higher than that of the balloon plus payload and thus the system continues to rise. Once the float altitude is reached, the air sampling operation is initiated by a combination of aneroid switch and timer. The sampling period was programmed to be between 3 and 4 hours, after which the balloon is cut off (by telemetry signal) from the payload by an explosive bolt (squib) and the payload descends by parachute. The descent took typically about 30 minutes.

Depending on the winds aloft, especially at altitudes above 100,000 feet, the system was likely to drift a considerable distance from the launch point to the impact location, in some cases hundreds of miles. The usual procedure was to follow the balloon visually and by telemetry on ground vehicles with the aim of reaching the package at its impact location as soon as possible to prevent tampering by “locals” and contamination of the internal sampling surfaces.

During that first flight in which I participated, we followed the balloon driving furiously in a generally westerly direction along which the prevailing wind carried it. As we crossed from Minnesota into North Dakota we stopped at a small town where we were accosted by the locals who had sighted the small dot in the blue sky and wanted to know whether we were government agents trying to track down this UFO. We had a difficult time convincing them about the true and innocuous nature of the observed “phenomenon”.

It was during this field expedition in pursuit of the balloon that I had my first – and last – exposure to root beer. During one of our stops, we went into a gas station to get a cold drink. The other members of the recovery crew – a highly experienced bunch – invited me to a “root beer”. I acquiesced gladly thinking – as a good greenhorn – that a “beer” is a beer. I took a long swig and…almost chocked on the unexpected and despicable taste of that most American concoction which has as much resemblance to beer as to orange juice. My collaborators were thoroughly mystified by my reaction.

More than one of the stratospheric sampling flights ended in disaster. At least two plunged into either Lake Superior or Michigan and were lost. At least one came crashing down shortly after launch when the balloon developed a massive rip. I witnessed the latter failure when the launch took place from Goodfellow Air Force base in San Angelo, Texas, the site of all later flights in which I participated. The recovery of the severely mangled payload took all day – a Friday. A follow up flight had been scheduled for the next Monday morning. I had the weekend to try to repair the mess. All components were transported to the main hangar of the base and I set myself to work, alone. I was provided with a tool box and no further support.

I managed to effect a fairly acceptable repair of the distorted protective frame of the electrostatic precipitator but, on Sunday, I discovered that the electrically insulating acrylic plate on which the high voltage power supply feeding the electrostatic precipitator was mounted was severely cracked and needed to be replaced. I ran around the entire hangar looking for a piece of insulating plate that I could adapt to my needs. There was absolutely nothing. I was beginning to feel that I would not be able to ready the system for the morning launch. I sat down and visually scanned the large hangar and suddenly my eyes landed on a wooden “No Smoking” sign attached above one of the entrance doors. I found a ladder, a hack saw, and proceeded to cut off half of the sign, an area that approximated the size of the shattered acrylic base. I drilled the appropriate holes and secured the power supply onto the wooden board and the latter to the payload frame. I ran an electrical test and everything seemed to be in working order. The next day we had a successful flight. I did not tell anyone about my act of sabotage of the No Smoking sign. I still smile when imagining the military employee who would first spot the mysterious dismemberment of the sign.

On one of the flights from San Angelo, the balloon was carried eastward at more than 100 miles/hour for most of the flight duration. We, the recovery crew, had to drive at breakneck speed all across Texas to the Louisiana border, and then back. I had the final driving night shift while the rest of the group was snoring away in the car.

It was during one of these field trips to Texas that I had an odd incident related to my native Spanish language ability. One evening after work, the balloon launching personnel and I, a group of eight, or so, decided to drive south towards the border to dine at a genuine Mexican restaurant. My companions were all acquainted with my knowledge of Spanish and decided that I ought to order the food by speaking to the Latino waitress in her own tongue. She was a young woman who, as soon as I started to speak to her in Spanish turned around and quickly walked to the back of the restaurant and proceeded to speak in hushed tones to a gathering of ominous burly mustachioed Mexicans. Shortly after, she disappeared behind a door not to be seen again. In her stead we were approached by one of those Pancho Villa types who, after eyeing us with an air of undisguised suspicion, took our order. Thereafter, for the duration of the meal, we felt an air of unrelieved tension in the establishment and were elated when leaving it. We all concurred that the Mexicans suspected that we were US government agents on a mission to smoke out illegal immigrants and that I was the Spanish-trained Anglo agent of the group. Henceforth I became much more parsimonious about flaunting my Spanish language abilities to Latinos in southwestern U.S.

♣

The laboratory work allowed me essentially free rein to solve many challenging measurement problems. Early on, when I was testing an axial fan designed to drive the air through the initial single tube electrostatic precipitator tube, I devised a method to determine the rotational speed of the fan. It consisted of using a variable frequency audio generator to which I connected one earphone, and placing my other ear on the test chamber within which the fan was running. I was then able to measure the fan speed by tuning the frequency of the audio generator until I heard the synchronous beat in my brain between the fan noise in one ear and the generator’s sound in the other.

One of my more original solutions was that of measuring the volumetric flow rate through the second generation 37-cylinder electrostatic precipitator sampler. This was a large flow rate system (1 m3/s) with a low pressure drop – basically an open flow configuration. No traditional flow meter could be used because of the inherently excessive flow resistance that such measuring device would create at the low air density that corresponded to the high operating altitude – a classic case of the measurement device influencing the measurement. We needed to be able to calibrate the ion tracer anemometer which measured air speed at one specific cross sectional location – not a true measure of the overall volumetric flow rate, but a measurement method that did not influence the process to be measured. My solution was to suspend the entire assembly as a pendulum, and measuring the deflection from the vertical position due to the thrust resulting from the net velocity gain between the larger inlet cross section and the narrower fan exhaust duct. I sensed the deflection by attaching a ferrite rod to the swinging assembly which moved into a coil of a resonant circuit. The degree of de-tuning was a measure of linear displacement. It worked like a charm, and I worked out the equation relating the deflection with respect to the weight of the system, air density and the flow dimensions of the assembly. As far as I know this flow rate measurement method had never been used before. But I was neither very patent-minded nor a promoter of my ideas and the technique remained unprotected and unused by others. I was to face the

effects of that detachment on more than one occasion over the years: I would think of a new approach, implement it and then forget about it only to find out that someone else patented the idea years later.

Another clever idea resulted in a portable electrostatic precipitator sampler for industrial hygiene applications that I developed together with Mort Lippmann. It incorporated a novel way to double the collection area without increasing the dimensions of the device by splitting the collection field as described in my first published paper. In that context I attended the annual conference and show of the American Industrial Hygiene Association in 1964 and because of my – by now recognized – expertise in electrostatic precipitation and the electrical behavior of airborne particles, I was called upon to critique a paper to be presented on that subject by Al Liebermann, a fairly well known technologist in that field. At that time, it was customary that the author and presenter of a paper at the conference would submit the manuscript to a reviewer several days ahead of the conference presentation. The reviewer then had the opportunity to present his critique following the podium presentation of the paper. Liebermann – contrary to the rules — provided me the manuscript late in the evening before his presentation, and I sat in my hotel room until past midnight until I finished the review. The paper was riddled with questionable statements and outright mistakes. In my typical brash manner, I unloaded my acerbic criticism at the allotted time to the shocked audience. It was not considered gentlemanly to express such an unmitigated negative assessment of a colleague’s work. I, however, could not care less. Scientific rigor needed to trump collegiality.

As I mentioned previously, the work at Del often left me some free time to devote to technical reading but also to the pursuit of some rather ‘extracurricular’ scientific activities. For

example, I wanted to find a simple method for timing events and/or measuring frequencies with great accuracy. I had a communications radio receiver at my disposal and used the timing clicks of the National Bureau of Standards WWV radio station to trigger a digital counter. While engaging in that pursuit, I found – by displaying those one-second ticks on an oscilloscope – that these clicks consisted of short sine wave bursts (i.e., a few cycles of 400 Hz) in the audible range, and yet these bursts did not sound like tones but like clicks. This led me to understand that, in order for us to perceive a sine wave as a tone, a certain minimum duration (or number of cycles) is required below which it sounds as a non-tonal click[3]. Another interesting psycho-acoustic phenomenon. These work unrelated pursuits satisfied my latent scientific curiosity without affecting significantly the timely performance

of my expected professional tasks. I was given a lot of freedom to pursue my own interests but I did not abuse that privilege.

♣

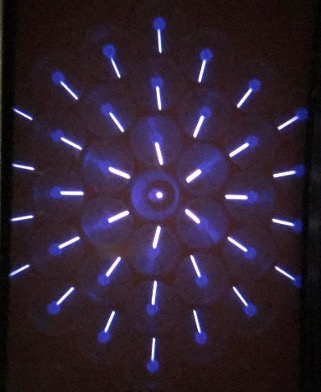

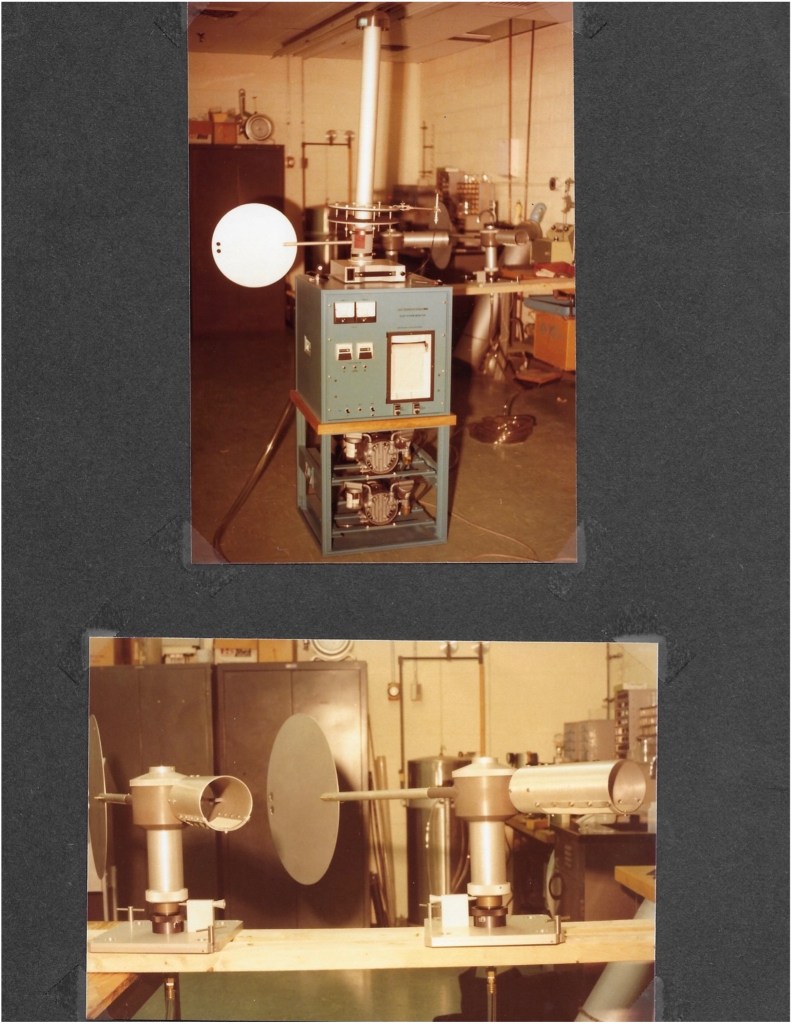

In the course of developing and testing the 37-tube stratospheric sampler, I made a serendipitous discovery of a previously unknown and – to my knowledge – unobserved

gaseous electrical discharge phenomenon. We started testing a single tube of the eventual cluster of 37 (this number arose from the compact hexagonal clustering symmetry of circles it provides, similarly to a cluster of 7 or 19 circles). We determined the corona current and

operating within altitude simulation chamber. View through a porthole.

voltage relationship, particle collection efficiency characteristics, flow resistance, etc. at air densities corresponding to altitudes between 100,000 and 150,000 feet. One of the critical parameters to be determined was the maximum voltage-current point at which the corona discharge remained stable without the possibility of localized spark breakdown which would obliterate the particle precipitation ability of the system. Once that maximum was established as a function of air density we would be able to design the high voltage power supply feeding the precipitator such that it limited the current-voltage to safe levels at any operating altitude. Logically, we expected that the maximum safe corona current of the 37 parallel tubes would be approximately 37 times that of the single tube. However, as soon as we assembled the first full 37-cylinder experimental system I found to my surprise and chagrin that the maximum achievable stable corona current was only about 22 times that of the individually running precipitator tube. That was potentially a serious setback since it would have resulted in a significant degradation of the particle collection efficiency of the overall system and would have forced us to reduce the sampling flow rate, an undesirable compromise.

I decided to try connecting a capacitor across the 37-cylinder precipitator to smooth out any unforeseen and unexplained electrical instabilities. This had a dramatic effect. Depending on the magnitude of the capacitance, the allowed (i.e., stable) precipitator corona current value rose to nearly 100% of the expected level (i.e., 37 times the current of a single tube). I then decided to connect an oscilloscope (with due precautions given the high voltage involved) across the precipitator to ascertain what instabilities there were in the absence of the smoothing capacitor. To my surprise, there was a large, essentially sinusoidal current-voltage component superimposed on the dc level, with a stable frequency of the order of several hundred thousand cycles per second (e.g., 450 kHz). My first reaction was that this oscillatory signal originated from some powerful neighboring radio station whose transmission somehow got into my high voltage wiring. I had a communications receiver available capable of tuning to the observed frequency but, again to my surprise, there was no detectable radio transmission at the observed frequency. The plot thickened. As I was pondering about the mysterious sine-wave signal displayed on the oscilloscope, I made a small adjustment to the control valve with which I changed the air pressure within the altitude chamber inside which the precipitator system was operating. Lo and behold, the frequency of the oscillation depicted on the oscilloscope changed with the air density! I was stunned. This was obviously not an externally generated signal – no radio transmitter in the vicinity – but an internal phenomenon associated with the corona discharge within the electrostatic precipitator. I confirmed that conclusion after replacing the high voltage power supply to eliminate the possibility of an unintended oscillation of that component.

Eventually, after careful review of the relevant literature – where no mention of this phenomenon under the observed conditions could be found – I concluded that the detected signal was due to coherent plasma oscillations of very large transiently formed ions (with molecular weights of several hundred) generated within the ionizing region or corona

(a) 0.02, (b) 0.012, and (c) 0.0046 atmospheres. Horizontal scale: 1 us/cm

sheath surrounding the axial wires. The creation of these large molecular weight ions apparently required the concurrent presence of nitrogen and oxygen at densities below about 1/50 of sea level values – I was unable to elicit such oscillations in corona discharges at sea level conditions. This was probably the reason why these stable oscillations had previously not been reported. Later on I also found that the frequency of the oscillations at a given air density and corona voltage-current point was influenced by the presence of gaseous trace contaminants, and I obtained a patent – my first one – for the sensitive detection of water vapor and other trace gases by this means[4]. Later on, while at GCA, I also found that these coherent oscillations failed to appear altogether when the corona was generated in the presence of a single gas species, e.g., CO2 or N2. This negated its possible use as a water vapor sensor for the first Mars lander. The atmospheric density at the surface of that planet was compatible with this sensing method but the absence of other gases than carbon dioxide precluded its application. Unfortunately I did not have the opportunity to further explore this interesting phenomenon to determine exactly what range of conditions were required to elicit it. I have also speculated on the possibility to perform trace gas detection by spectroscopic analysis of the electromagnetic emission from the visible corona discharge glow surrounding the axial wire. Maybe a future researcher could pick up this idea and explore it further. If I had discovered these ion plasma oscillations while researching within an academic setting they would probably have been made famous as the “Lilienfeld Oscillations”. Alas, I was in an industrial environment and it certainly was remarkable enough that I had the chance to identify a heretofore unknown gaseous electrical discharge phenomenon.

In the course of developing the ion tracer anemometer that I described above, I became acquainted with certain facets of flow dynamics which had been previously unfamiliar to me. The detection pulse shown on the oscilloscope provided clear information as to whether the flow was in the laminar or the turbulent regime. These observations led me read the scientific literature on related topics expanding my overall knowledge of this field.

I had the opportunity to experiment with what is called ion wind, the air motion generated by a corona discharge, for which I developed equations to predict the flow rate produced by such gaseous electrical discharges.

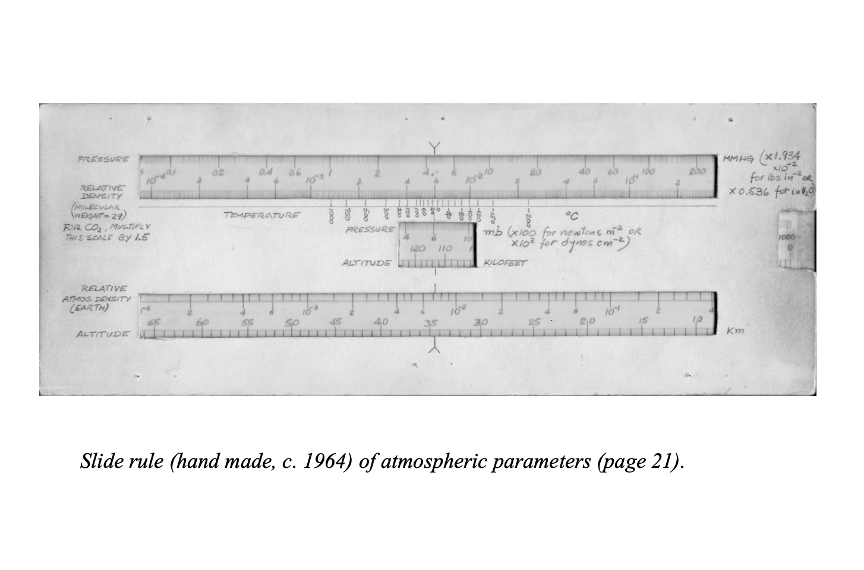

In my few relatively idle moments – when waiting for an experiment to run its course – I designed and made a slide rule to calculate pressure, density, temperature and other parameters as a function of altitude. I still have that manual calculator which I never took beyond that prototype level (see photo of slide rule in Photo Gallery at the end).

♣

Eventually, this whole project reached its conclusion. In 1966, the Atomic Energy Commission decided that stratospheric sampling related research was no longer justified because the test ban treaty between the US and the Soviets had terminated any further nuclear detonations in the atmosphere. Leonard Solon departed DEL and I was left to wind up the work. Eventually, Solon and I wrote an extensive paper about the project that was published in Europe. Since this had been the only activity at DEL related to research and development of airborne particle instrumentation, I was forced to return to my original assignment when I had joined the company six years earlier, namely power supply circuit design and development. This involved working for the chief engineer, a Jim Constable, a capable but notoriously obnoxious individual who treated his engineers as if he were running a fiefdom. I decided to bid my time at DEL while exploring more interesting job opportunities elsewhere.

My friend Dr. Mort Lippmann suggested I follow him to NYU’s Sterling Forrest research facility and that I apply for a PhD program there in biophysics. Although I was not too tempted by that suggestion, I felt obligated to contact Dr. Roy Albert, the head of that department for whom Mort was working at the time and to whom he had spoken about me. When Dr. Albert heard that I played tennis he suggested I bring my racket and sneakers to my visit to that Westchester campus. Thus it became a rather original interview carried out while exchanging fore- and backhands across the court with Dr. Albert. I did not hold back and he lost. Eventually, I received an offer from NYU which I declined. I decided that the biophysics career would take me too far afield from the area of expertise in aerosol instrumentation that I had fallen into over the preceding six years, or so. I was not inclined to be subjected to a plethora of courses in anatomy, physiology, toxicology, etc. that were prerequisites of the NYU degree.

At GCA/Technology Div.

One Sunday morning in late 1966, Evelyn, while perusing the jobs section of the New York Times, pointed out to me an advertisement for an “aerosol physicist” at a company in Bedford, Massachusetts called GCA/Technology Division. I looked on a map and could only find New Bedford on the southern coast of that state. I responded to the ad and they invited me for an interview in early December. Evelyn, Claudio and Armin accompanied me and we drove to Bedford which GCA had informed me was a suburb of Boston. The interview lasted a good part of one day as I was queried by five senior staff members. The next day I visited AVCO, an aerospace company, with which I had also arranged an interview. Both companies offered me a job but the fit with GCA was decidedly better and I accepted.

The starting salary at GCA was significantly higher than my extant pay at DEL – $15,600 vs. $12,500. When I informed Mr. Delcau, the president of DEL of my decision to leave his company he took that as a personal affront but my decision was irrevocable and we parted somewhat less than amicably. We moved to our newly rented home in Lexington on March 18, 1967, a Saturday, and I started work two days later at GCA.

At that time, GCA/Technology Division was a high powered contract research organization of some 250 employees, 90 of which sported PhDs. At first, but only for a very short time, I felt a bit intimidated by all that concentrated brainpower. This group was one of the divisions of GCA Corporation. The other divisions were various laboratory instrument manufacturers that had been acquired by GCA in recent years. GCA/Technology division had been the original core when the overall company – Geophysics Corporation of America – had been founded in the early 60s as a spin-off of the Cambridge Research Laboratories of the US Air Force at Hanscom Field in Lexington. GCA/Technology Division specialized in contract research for various government agencies in the general field of atmospheric and planetary physics and chemistry. The aerosol group into which I was integrated did most of its work under contract from the US Army in research related to the generation and dispersion of chemical agents. My immediate superior was Arnold Doyle, a very engaging and personable individual with whom it was a pleasure to work. Others in the group included David Lull, an explosives specialist and Paul Morgenstern[5], a meteorologist/mathematician.

I gradually interacted more and more with senior staff members from other groups, such as the chemical physicist Abe Berger, the physicists Earl Rosenblum and Jerome Pressman, the department head John Ehrenfeld, George Ohring, a senior planetary meteorologist, Henry Miranda[6], a physicist, Carl Accardo[7] and John Dulchinos[8], both electrical engineers, and several others. I soon discovered that I had been hired to replace an aerosol specialist called Bob Gussman who had left to form a small spin-off company. In later years I was to become well acquainted with my predecessor at GCA, who eventually went on to found BGI with Charles Billings, a respected aerosol physicist (Billings & Gussman, Inc.). Also, Shortly after I joined GCA, Arnold Doyle received a call from Richard (Dick) Dennis, a particle filtration specialist, who had been at GCA previously and had joined Bob Gussman. Dick wanted to return to GCA after that joint venture (with two other people) had split apart. He was thus rehired as a senior aerosol staff member. A few months later Charles Billings also joined the group. The latter contributed little or nothing to the work at hand as he concentrated almost exclusively to the writing of a book on industrial hygiene aerosol measurement methods. He eventually left GCA and proposed that I join him in forming a two man company. I refused (I found Billings to be too mercurial and unpredictable) and he then joined up with Bob Gussman as I mentioned above. That association was to be short-lived as well; Billings left and Gussman took over retaining the name BGI for his company as it is still known today.

I found, to my great relief, that most of the scientists at GCA shared my views about the Vietnam war, as opposed to the professionals at DEL. However, once more, some of the engineers seemed to be rather reactionary, like those at DEL.

♣

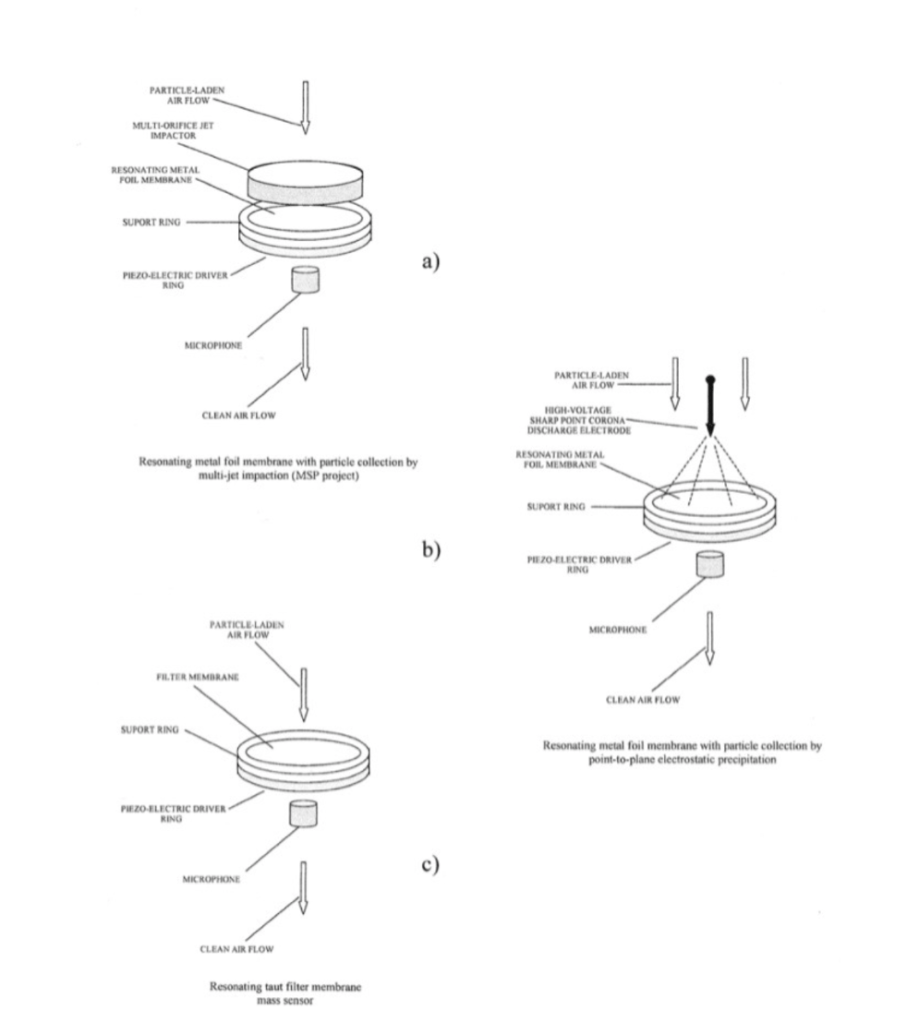

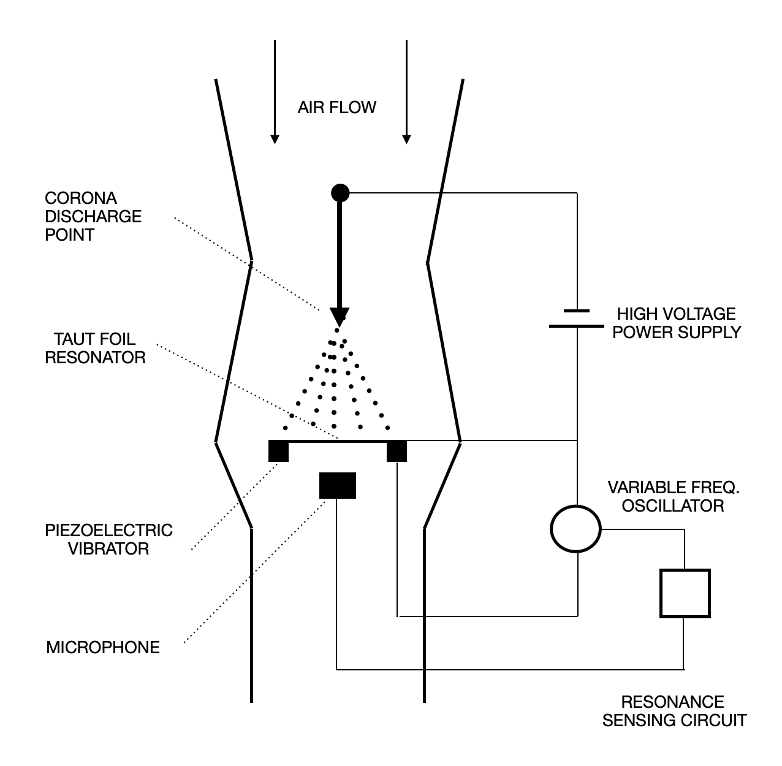

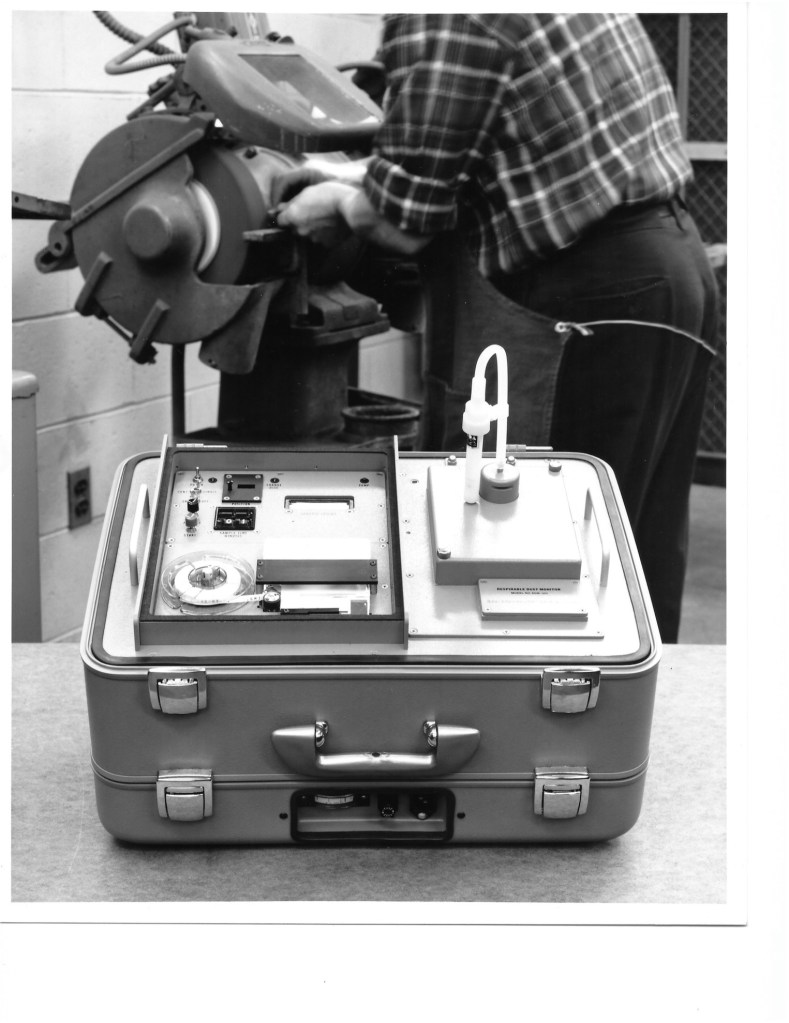

One of the major projects that engaged my attention within a month of joining GCA was to develop a real-time particulate matter mass sensor to be applied to large chamber- simulated chemical agent dispersion tests. Arnold Doyle and I converged on a combination of particle impaction and beta radiation attenuation mass sensing for which we were granted a joint patent[9]. It was to be a successful idea that first culminated in a prototype device used on the aforementioned tests at GCA, and later (as I will describe in some detail) in the first direct reading portable particle mass monitor ever developed, and the first commercially produced instrument at our division of GCA.

The motivation for the overall research program, under the sponsorship of the US Army, was of course rather distasteful to me, at the very least. Its main objectives were to investigate and optimize methods of dispersion of chemical agents, principally for riot control, but probably with more nefarious ultimate purposes. Most of the time we worked with harmless simulant materials, but not too infrequently, tests were performed with the real stuff inside a very large cylindrical cement chamber behind the company’s parking lot. Those tests were conducted by explosive dissemination of the agent substance, at which time an alarm would be sounded to alert everybody of the imminence of the test. The explosion itself was usually heard, in my office in the main building, as a dull thud.

I seldom participated in those tests, as most of the time I worked on the development of measurement, sampling and detection methods in the main laboratory. After each test with the actual agents, the test chamber had to be thoroughly decontaminated with high pressure water or solvent jets. Once, I needed to enter the chamber after one of those tests and somehow touched the internal wall and within seconds started to feel an unbearable itch that extended over all my exposed surfaces. I had to run to a shower station to wash off the irritant. I could only imagine the sensation of any victim of direct exposure to the undiluted agent!

Occasionally there were protest pickets by groups of “beatniks” who advocated the termination of these tests, and the local police had to be called in when they got too disruptive. The real agents tested were CS and VX. My personal extreme itch experience was with the former of these. Every Monday morning a medical team set up shop in an office at GCA and we all had to give a blood sample for analysis in case of accidental exposure.

Among other devices, I designed an automated air sampling system to rapidly and sequentially collect the particles, generated within those chamber tests, on a series of filters for subsequent analysis. In addition to the work for the Army, I got involved in several other projects where aerosol and gas detection expertise was required as well as in areas related to air flow, temperature, pressure, atmospheric visibility and other environmental measurements.

§

I had started at GCA/Technology Div. March 20, 1967. The next year, and especially in early 1969, Nixon’s accession to the presidency was accompanied by a severe cutback in government funds to support research – any research. A rather typical republican approach to government. The immediate result was a drastic elimination of jobs among the senior program managers and scientists of the organization. On a daily basis, there were goodbye parties and emptying offices. It became a thoroughly dispiriting and unsettling environment, and I began to feel somewhat insecure although the Army project on which I was working seemed to be unaffected by the widespread cutbacks affecting other projects. One evening, after I had just returned home from work, I received a phone call from the department head, Arnold Doyle. He wanted to know if he could come and visit me at home a few minutes later. With a thoroughly uneasy feeling I awaited his arrival. I could only imagine that he wanted to inform me in person about my dismissal. A very personal gesture, indeed. He arrived, I led him to our living room and he proceeded to tell me that he just wanted to set my mind at ease, that my job was assured for the time being, that my services were essential to the project, and that I had been doing exceptionally good work. I will never forget this uniquely empathetic gesture by a particularly humane and caring manager, an extreme rarity indeed.

Sometime later, the overall section director, Dr. John Ehrenfeld, threw a party at his home, purportedly to counterbalance the doom surrounding all those good-bye parties, inviting those members of his staff who remained at GCA. Two days later he himself was laid off. He summoned me into his office where he sat red-faced and angry. He proposed that I leave GCA and join him in a new technological venture that he was hatching. I demurred, claiming – legitimately – that I had been at GCA for only a short time and saw no reason to change my job at that point. As I mentioned before, Dr. Charles Billings was to make me a similar proposition a few months later. Dr. Leonard Solon, my erstwhile boss at DEL Electronics, had also wanted me to join him in some hypothetical venture. I seem to have had some appeal to all those technocratic venturers.

Very soon after the beginning of this upheaval, in 1968, I witnessed at GCA a very strange behavioral transformation affecting certain members of the staff who had not been included in the early round of layoffs. Almost overnight some individuals who were up to then inconspicuous, clean cut, all-American looking young men, became odd-looking mountain men with long hair, beards, mustaches and other facial shrubbery. Dr. Rosenblum, the somewhat elderly physicist, with whom I had been working on a contrast photometer development project for the government, left the company, abandoned his family, bought a camper vehicle and disappeared into the boondocks of Northern Canada. A young engineer prepared to live under extreme privation in the wilderness with his wife and toddler-age children by selling all the furniture in his house and sleeping in bags. Neither was ever heard of again. One senior German scientist committed suicide. The social fabric was being disrupted severely as part of the 1968 phenomenon.

Eventually, over the next year or two, the roster of the GCA/Technology Division staff plummeted from its peak of about 250 to merely 65, or so. Arnold Doyle and several of the people working for him departed and formed one of several spin off companies.

Finally, after a major administrative reorganization, a new general manager, Dr. Leonard Seale[10], took command and decided, wisely, to reorient the Division’s activities towards the newly evolving field of air pollution research, a natural field for scientists and engineers previously engaged in high atmosphere studies. As we got deeper into the 1970s, the federal government began to support programs in this emerging field, including industrial hygiene monitoring. I became exceedingly successful in winning competitive research and development projects throughout that period. I will endeavor to describe these activities in what follows.

As part of the reorientation of our division’s objectives, several new scientists with capabilities in the emerging environmental field joined the organization. I became quite friendly with several of them. Most notable among these were Paul Fennelly, Bob Bradway and John Driscoll. Shortly after, Steve Chansky was hired and with whom I worked quite closely as he eventually was placed in charge of marketing the particulate monitoring instruments that I was developing. As to John Driscoll, he left GCA a few years later and when eventually I met him again he had undergone one of those remarkable transformations I had mentioned before. His name had become Jack Driscoll and his appearance and demeanor had evolved from a soft spoken all-American clean cut nice boy to a broadened, boisterous, self important walrus-mustachioed individual. He was by then the president of a small company called HNu specializing in photoionization gas detectors. Sometime, in the 1980s he became interested in acquiring my particulate instrumentation group but he was unwilling to come to terms with GCA on this matter – fortunately, in retrospect.

In the meantime, I was working on the development of an advanced airborne particle counter incorporating a gas laser, a newly introduced device uniquely suited for that purpose. The work was performed under a contract with the Air Force. The instrument was designed to be mounted within a wing pod of a high altitude research aircraft and to be flown at about 65,000 feet. One of the facets of this project required the determination of the operating temperatures of some critical components of the system such as the high voltage power supply of the laser, the laser itself, etc. This was a matter of concern given the low air density to be encountered at altitude and the attendant diminished air cooling of these components. The Air Force decided to issue a secondary contract to the University of Dayton where a group had become specialized in computer modeling of thermal processes. We provided them with all the relevant information to carry out their calculations. Some months later I received in the mail from the U. of Dayton a 2-inch thick stack of computer printouts with tabulations of the predicted temperature rises of various critical system components as functions of operating time and altitude. I looked at a few of these tables which indicated that the components that were expected to heat up the most (e.g., the laser high voltage power supply) would, under the worst conditions, undergo a total temperature rise of about 1 °C in about 100 seconds, after which the temperature would remain essentially constant. I knew immediately – from my own experimental evidence gathered at DEL in the altitude chamber – that this was “garbage” information. I had run tests of similar equipment that showed typical temperature increments of about 50 °C over periods of the order of 2 hours. In my usual brash manner, I communicated my assessment to the head project scientist at Dayton. He was quite horrified by my dismissive characterization of their results but I stood firm and contacted the Air Force telling them, in so many words, that they had wasted their money. Eventually, they checked the results and came to accept my view. It was my first experience with the computer age dictum ‘Garbage in, garbage out’, that summarizes the pitfalls engendered by too much reliance on massive computational power and too little ‘back-of-the-envelope’ pre-calculation, if not actual experimental experience.

Since most of the original researchers who had worked on the Army project of aerosol dispersion characterization had left by early 1969, I was charged with winding up that project and called upon to write the final report. Another wind-up of a major project that was to fall on my shoulders similarly to the stratospheric sampling project for the AEC at DEL.

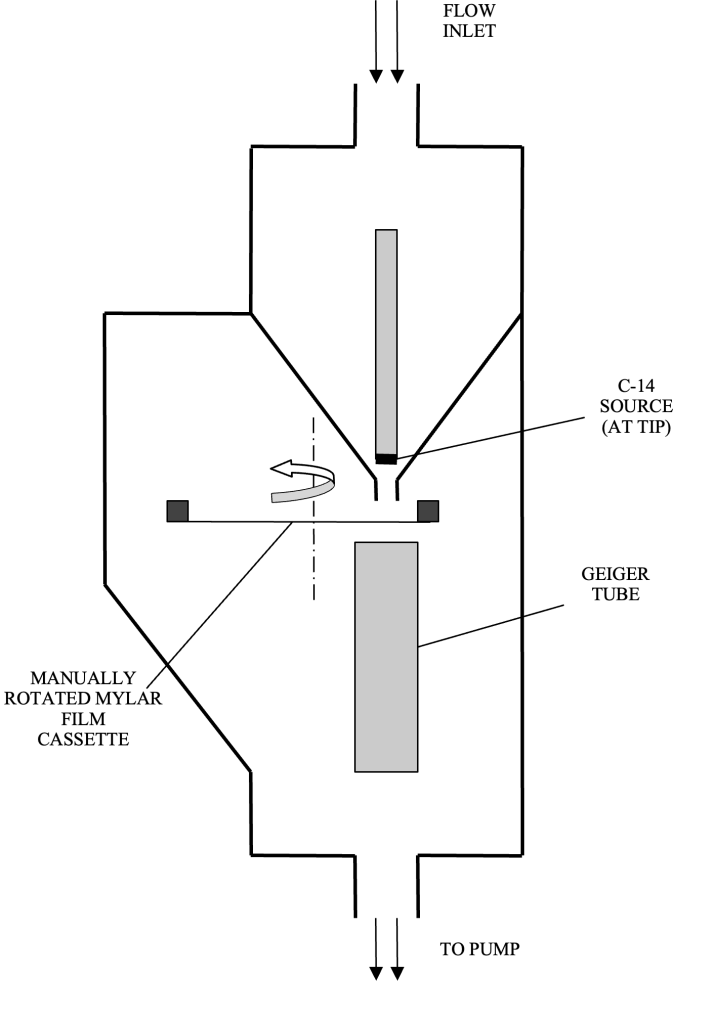

Beta attenuation instrumentation

Early in 1969, the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) issued a request for proposal for a direct reading particulate mass monitor to be used in coal mines. Based on the above mentioned work on combining beta radiation and particle impaction that I had performed within the Army project, I wrote a proposal for the development of such an instrument. This was my first proposal which I authored alone. Previously, I had only contributed to the preparation of proposals written jointly with other scientists. My proposal to NIOSH was successful and GCA received the contract. I was elated, and promptly dove into the design and development of that pioneering instrument, with the support of a most capable electronic design engineer – John Dulchinos – and a mechanical engineer of Dutch extraction whose name I have forgotten – perhaps for good reason. We built a prototype unit to be delivered to the government. Upon its completion, we decided to travel to Pittsburgh for a show-and-tell to two other agencies: the U.S. Bureau of Mines and the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) which were obviously interested in a device to measure coal mine dust. The general manager, Leonard Seale and I arrived in Pittsburgh during an ice storm and proceeded to make the presentation of the new instrument to a gathering of about a dozen government staff. Their reception, however, was as icy as the weather. We became aware that they considered this development as an interagency interference (NIOSH vs. the Bureau and MSHA) and we found ourselves innocently caught in between. On leaving the meeting, I decided to lighten the mood and expressed my disappointment about the weather upon which the principal researcher of MSHA – Murray Jacobson – retorted angrily that he had nothing to do with that. In years to come, however, he was to become quite friendly and tractable.

This portable instrument was to become the first commercial product of GCA/Technology Div. as the model RDM-101. Several hundred – perhaps more than one thousand – of these devices were sold, starting in 1971, but not before I had to learn that particle impaction has its idiosyncrasies that had to be overcome in order to ensure the appropriate performance of the instrument. The impaction surface needed to be coated with a thin layer of a mixture of Vaseline and oil, viscous enough to not flow but fluid enough to wick over the particle surfaces in order to continue presenting an adhesive surface to subsequently impacting particles. That special condition was achieved by mixing some fine dust into the Vaseline/oil mixture to make it into a “non-Newtonian” fluid. This was the early contribution to this project by a newly arrived very bright young physicist, Dr. Douglas Cooper, who was to collaborate with me on several subsequent projects.

The RDM-101 portable mass monitor became the first of several “variations of a theme”. Other related instruments followed such as the RDM-201 which used a small filter in lieu of the impactor, the RDM-301 which incorporated an automatically advancing mylar cassette instead of the manually indexed one of the RDM-101, and a large filter tape version named the APM-1. All of these devices sensed mass by the attenuation of carbon-14 beta rays as sensed by a Geiger-Müller detector tube.

In 1972, it was decided that I should take a trip to several European countries to demonstrate the newly developed RDM-101. Evelyn accompanied me and we traveled to France, Germany, Switzerland, and the UK. The trip almost started with a disaster. We arrived in Paris from the U.S. and took a taxi to my ancestral home in Boulogne-sur-Seine where my step grandfather Louis Fourestier lived with his wife Lucette Descaves.

After the taxi departed we discovered to our horror that we had left the instrument in that car. Fourestier tried, unsuccessfully, contacting various cab companies to trace the missing device. Suddenly, about an hour later, the house bell rang, and our Moroccan taxi

driver was standing at the door with the missing RDM-101 in its carrying case. We gave him a generous tip and breathed a sigh of utter relief. Our thoroughly jet-lag addled mind had nearly derailed the entire trip. So much for North African sly dishonesty!

The rest of my marketing sojourn was decidedly more uneventful. Two instances stand out. I made a presentation at a Swiss research agency in the presence of half a dozen

scientists. I had worked out a practical demonstration procedure producing a cloud of dust by blowing across a blackboard eraser. At that time there were still real blackboards on which one wrote with chalk sticks (sounds prehistoric now). The eraser was usually permeated with chalk particles. I did my chalk blowing in the vicinity of the instrument and got a reading of 4.3 milligrams per cubic meter, and I showed the display to the gathering. I then repeated the chalk blowing and got a reading of…..4.3 again. A third time, and the reading was…..4.3. The assembled group started to look at each other in skeptical and mocking disbelief – this instrument has just one reading: 4.3. My discomfort became palpable but I did not relent. I performed the test a fourth time and to my – and the gathering’s – utter relief the reading was 5.8.

The other idiosyncratic case was my visit to a French nuclear research facility in Provence where Evelyn was constrained to remain in the guard house for several hours – for reasons of security – while I was allowed inside the facility. She was engaged, however, to her surprise, in a long and learned dialogue with one of the guards about Gallo-Roman antiquities in the area. I, on the other hand, experienced the curious hierarchical stratification of the French professional establishment. The scientist who received me at the gate was supposed to introduce me to a more senior administrator. This process consisted of the scientist and I standing in the corridor next to the door to the chief’s office until he deigned to open his door which took at least one half hour.

In general the new instrument was well received in Europe although with a bit of the customary “not-invented-here” diffidence.

In 1975 I wrote a review paper on the use of beta attenuation as applied to the monitoring of airborne particulate mass concentration which I presented at an international aerosol meeting near Bonn, Germany, and which was published in the German journal Staub.

I had by then become the guru of beta radiation attenuation as applied to particulate mass determinations – my second major “guruness”.

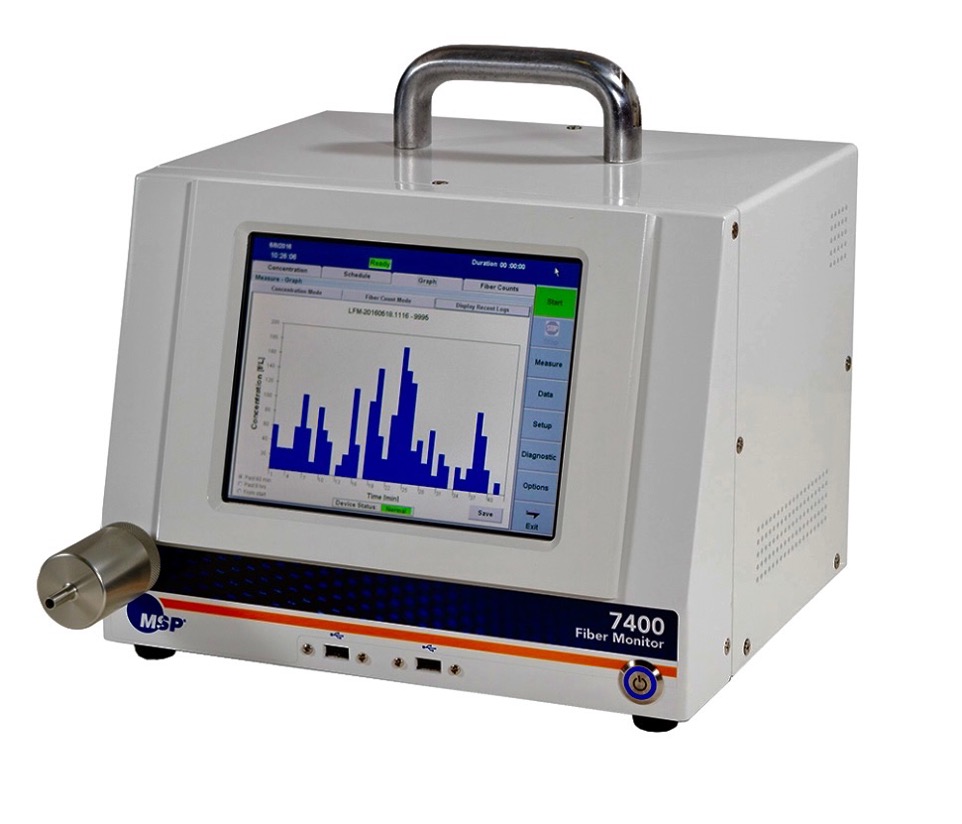

The fiber monitor story

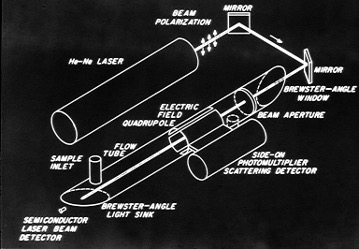

In late 1972, while at GCA, I contributed to the writing of a proposal – one of many – to the Environmental Protection Agency, related to asbestos research. As I was sitting in my office working on that subject, I had one of those inventive sparks. It was triggered by the awareness that the standard method of monitoring airborne asbestos fibers was by collecting an air sample on a filter, and then taking that filter to a laboratory for microscopy analysis which, in essence, consisted of laboriously sizing and counting the fibers visually one by one. The results were delayed, typically, by a week, or more. My invention insight was that these microscopic fibers, typically 5 to 10 micrometers in length, should align and swing their axes when subjected to a time-varying electric field, and if illuminated concurrently with a concentrated light beam – such as from a laser – should exhibit a modulation or fluctuation in their scattering of that light. This would provide a means to detect the presence of fibers in real time. After I had mulled over the idea for a few minutes, I marched into the office of the senior aerosol technologist, Richard Dennis, and described to him the concept that I had hatched. He seemed interested and exhibited at least a glimmer of understanding of my explanation. Dennis was an old timer who was decidedly better at dealing with mechanical systems such as filter bags. More about him in this context later on in this narrative.

I had to establish the feasibility of the method, and I helped Doug Cooper to set up and run the crucial experiment needed to prove whether my idea had any merit. I used a sine-wave generator whose output was boosted with a transformer to create the time-varying voltage across a couple of plates within a glass tube along which we shone a laser beam. The scattering of the laser light was detected by a photo-multiplier tube connected to a phase-sensitive amplifier, a device that measures the amount of detected signal that is synchronous with the time varying electric field. We generated an air stream containing asbestos fibers flowing through the glass test tube. Lo and behold! We immediately detected the expected signal which we observed only in the presence of the fibers and when the varying electric field was activated. Success and elation. After further confirming tests, the company decided that I should write a so-called ‘unsolicited’ proposal to the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), the same government agency that had supported the development of the portable coal mine dust mass monitor. Unsolicited proposals, however, were considered low probability attempts to secure government support. It implied that you knew better than the agency on what its funds should be spent, and even more importantly, the agency in question was unlikely to have budgeted for a project it did not know about beforehand.

Nevertheless I proceeded with the preparation of the proposal and GCA submitted it to NIOSH. For several months we heard nothing but suddenly we were informed that NIOSH had decided to fund the development of the fiber monitor based on the principle I had come up with. That was decidedly a feather in my cap and it seemed that this project would follow smooth sailing. Not so, however. As the final financial negotiations between GCA and the government were underway, we suddenly received notice from NIOSH that the procurement, and thus the project, had been cancelled. What had happened? Eventually, we were informed that a competing company in California had – through a state representative in Congress – issued an injunction to stop the contract with GCA, claiming that that firm had submitted a competing – also unsolicited – proposal for a related instrument development. The apparently frightened cancellation by NIOSH of our project was in the immediate aftermath of the infamous Watergate scandal, and any intimation of impropriety – even if unsupported – elicited a knee-jerk paralysis reaction in a vulnerable industrial safety agency. We were thoroughly disappointed, but were told by NIOSH officials that this situation would force the agency to follow the standard route of publishing a competitive proposal solicitation. After nearly a year that Request for Proposal (RFP) for a real-time fiber monitor was announced (through the Federal Register) and NIOSH went the extra step to call for a bidders meeting in Washington where all organizations interested in submitting a proposal could be instructed about the purpose of the procurement and to ask questions from the government in the presence of all the potential proposers. I attended the meeting but, to my surprise, the objecting California company that had blocked the original contract, was absent. Among those present was Dr. Knollenberg, a highly respected designer of advanced optical particle counters. To my quiet amusement – and that of the NIOSH officials already aware of my technique – he affirmed during the meeting that the real-time selective detection of fibers – in the presence of many particles of other shapes – was physically impossible. Even the most capable among us can be dead wrong.

I prepared a new proposal, incorporating the specific technical requirements that NIOSH had stipulated in its RFP and submitted it. Predictably, we were eventually informed that GCA obtained the contract. Dr. Paul Baron[11]was the NIOSH contract monitor. This time no injunction could be issued by any party as the procurement had followed the competitive route. We started the work immediately (early 1976) and, with crucial contributions of Dr. Paul Elterman, a physicist we hired for the project, we developed a prototype “fiber aerosol monitor” (FAM) which we delivered to NIOSH in 1977. It demonstrated the usefulness of the method but also showed some room for improvement before we could commercialize the instrument. In the prototype the fibers were induced into complete (360º) continuous rotation by the applied electric field. This was accomplished by using two pairs of electrodes at 90º with respect to each other, and

applying two sine-waves to these pairs, 90º out-of-phase. This generated a rotating electric field of constant intensity. Dr. Elterman came up with the approach eventually incorporated in the commercial versions of the FAM. It consisted of applying two different sets of superimposed potentials to the four electrodes, one constant and the other, a sine-wave at 90º. This resulted in an oscillating electric field that induced a similarly oscillating motion to the fibers passing through the sensing tube of the instrument. This approach increased the time during which the fiber-induced scattering signal could be detected.

In 1978 we designed the commercial version of the fiber monitor and called it model

FAM-1. Its most immediate and important application was to monitor asbestos removal operations that around that time were becoming quite frequent as the concern for the negative health effects of asbestos exposure were being identified. Our initial sales of the instrument were enhanced by the interest evinced by research organizations, universities, government agencies both here and abroad. In 1979 the FAM-1 was included in the IR-100 list of most notable industrial developments of the year and I attended a black-tie dinner ceremony at the Technology Museum in Chicago. Leonard Seale the general

manager of GCA/Technology Div. lent me his tuxedo (I did not and never have owned such a garment).