At the outset I must confess that this is a fraught subject and I don’t want to pretend that I am in the position to proclaim a solid opinion nor a solution to a very convoluted problem. Nevertheless I intend to structure a view notwithstanding the limitations of my own knowledge of all the facts bearing on this complex matter, to which I would like to add that I doubt that there are people who could claim such all encompassing understanding of one of the most critical and consequential problems of our time.

Historical Background

I have addressed some aspects of Christian antisemitism, its origins, trajectory and culmination in my essay #30 of the Aleatory Cogitations, entitled “German Antisemitism and the Holocaust”. I want to concentrate and expand on this subject in what follows, especially in the context of the convoluted situation that we are facing today (2025).

For a thorough compendium of the two-millennia relationship between Christians and Jews the reader is referred to a Wikipedia entry entitled “Antisemitism in Christianity”.

The impetus for revisiting this fraught history has been a series of dialogs that I have had, recently, with my good and learned friend MIT Prof. Stephen VanEvera, Professor of Political Science, Emeritus, who has coined the concept of “Holocaust Before the Holocaust” to characterize the long history of persecutions, expulsions and mass killings that European Christianity has inflicted on the Jews. In other words, it is imperative to recognize that the horrendous German Holocaust of Jews of the 20th century was preceded by a relentless series of Christian incited “holocausts” maybe starting with the First Crusade (1096 AD), if not earlier.

Perhaps the original source of the denigration of Jews can be traced back to Matthew 27:24–25: So when Pilate saw that he could do nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took some water and washed his hands before the crowd, saying, “I am innocent of this man’s blood; see to it yourselves.” Then the people as a whole answered, “His blood be on us and on our children!” (my emphasis). That accusation of deicide was to be the curse that provided the principal motivation and justification for the repeated outrages by Christians against the Jewish people throughout the centuries.

The origins of the antisemitism leading to the repeated massacres and other outrages of Jews, especially during the Middle Ages, can be further traced back to the pronouncements of the early Church fathers within the realm of the Roman Empire. In chronological order, the following are several of the most outspoken of these early slanderers of Jews, some of which are revered today as saints: Tertullian (155 – 240), Cyprian (210 – 258), Ephrem the Syrian (c. 306 – 373), Jerome (c. 342 – 420), John Chrysostom (347 – 407) and Agustin of Hippo (354 – 430).

Even earlier, it is worth mentioning the rantings of Melito de Sardis (c. 100 – c. 180), venerated in both the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. As his Wikipedia entry informs us, he was not satisfied with dismissing Judaism as misguided, and compared Jewish practice to a first draft that, in the wake of Christianity, ought to be “destroyed” or “dissolved”. He closes with the fervid accusation: you smashed the Lord to the ground, you were razed to the ground. And you lie dead, while he rose from the dead.

The history of the massacres of Jews, following the first major one in 1096, is a painful litany of repeated outrages that will not be addressed herein. But, as I pointed out in my #30 essay, referred to above, the outrageous accusation of deicide, in addition to other falsehoods, such as blood libels, poisoning of wells, witchcraft, abduction of Christian children and more recently, world domination, conspiracies, treason, etc. fomented and promoted never ending fountainheads for antisemitism.

The repeated refusal of the majority of Jewish communities to their forced conversion to Christianity provided further fodder for the hatred they engendered. As I cited in the aforementioned essay, that resistance against abandoning the Jewish religion motivated Martin Luther’s rantings against the Jews and the writing of his notorious antisemitic tract On the Jews and Their Lies.

The question has been raised whether this rather calamitous perspective of Jewish history, in the Christian realm, constitutes a “lachrymose” view, i.e., a negatively biased one that assumes that the Jewish people were being decimated relentlessly through the ages, without due consideration of periods of peace and even boom.

My view is that, notwithstanding such occasional periods, such as life for the early Jews in Hispania and the rest of southern Europe had been relatively tolerable during the 5th and 6th centuries, under early Visigothic rule. This was due, in large measure, to the difficulty the Church had in establishing itself in its western frontier, and for several centuries the Jews enjoyed a degree of peace their brethren to the east did not. However, once the Visigoths under Recared adopted Catholicism in 587, the Jews in Spain were vilified and relentlessly pressured to convert to Christianity, such as under Sisebut, king of the Visigoths from 612 to 621, who mandated that every Jew who would refuse for over a year to have himself or his children and servants baptized would be banished from the country and deprived of his possessions.

The Jews of Spain were utterly embittered and alienated by Catholic rule at the time of the Muslim invasion of 711. The Moors were perceived as a liberating force and welcomed by Jews eager to help them to administer the country. In many conquered towns, the Muslims left the garrison in the hands of the Jews before they proceeded further north, which initiated the Golden Age of Spanish Jews. That period, however was punctuated by fluctuating acceptance of Jews, depending on the whims of local rulers and Church authorities. During the Reconquista, the gradual reclaiming of the Spanish territory by the Christians, the fate of the Jewish communities in Spain oscillated between full acceptance and oppression, compounded by persecution by the fanatical Almohad moslems.

The defining turning point for the Jews in Spain came in about 1250. Their fate became increasing precarious as Christian antisemitism grew. In 1328, 5,000 Jews were killed in Navarra following the preaching of a mendicant friar. In 1355, a mob in Toledo murdered 1200 Jews; in 1360, all the Jews living in the city of Nájera were killed; in June of 1391 a mob incited by Ferrand Martínez, the archdeacon of Sevilla, attacked the Judería of that city from all sides and killed 4000 Jews; the rest submitted to baptism as the only means of escaping death.

These massacres of Jews in Spain, starting in the 1300s, spread to the entire Iberian peninsula culminating with the establishment of the Inquisition in 1478 and, finally with the Edict of Expulsion in 1492. The interested reader will find an interminable compendium of outrages against the Jews in Spain in a Wikipedia entry entitled “History of the Jews in Spain” from which some of the above details have been obtained.

The history of the Jews in Spain is rather symptomatic of what ensued over the centuries in other western European countries. Expulsions, persecutions and massacres elsewhere often preceded those that I described in Spain. Most of these outrages were carried out by mobs that were, in turn, incited by religious intolerance. For example, in England the absence of Jews after their expulsion of 1290 included the belief that England was therefore unique because there were no Jews, and that, consequently, the English had superseded them as God’s chosen people.

The expulsion of Jews in England was preceded by a series of massacres of which the most notorious was that in York in 1190. Here is the Wikipedia description of that terrible incident:

A significant loss of life occurred at York on the night of 16 March (Shabbat HaGadol, the Shabbat before Passover) and 17 March 1190. As crusaders prepared to leave on the Third Crusade, religious fervor resulted in several incidents of anti-Jewish violence. Josce of York, the leader of the Jews in York, asked the warden of York Castle to receive them with their wives and children, and they were accepted into Clifford’s Tower. However, the tower was besieged by the mob of crusaders, demanding that the Jews convert to Christianity and be baptized. Trapped in the castle, the Jews were advised by their religious leader, Rabbi Yomtov of Joigny, to kill themselves rather than convert; Josce began by slaying his wife Anna and his two children, and then was killed by Yomtov. The father of each family killed his wife and children, before Yomtov and Josce set fire to the wooden keep, killing themselves. The handful of Jews who did not kill themselves died in the fire, or were murdered by rioters. Around 150 people are thought to have been killed in the incident.

In this context, it is essential to consider the effects of forced conversion and expulsion on communities, especially highly bound ones, such as the Jewish ones in the Middle Ages. Forced conversion was equivalent to breaking with all ties to ancestral rituals and beliefs. Expulsion meant ostracism and uprooting that was nearly equated with a death sentence. These were suffered by the Jews of that time as wantonly cruel acts and their impact ought not be judged through modern eyes. These outrages have to be considered as decidedly complementary and nearly equivalent to massacres.

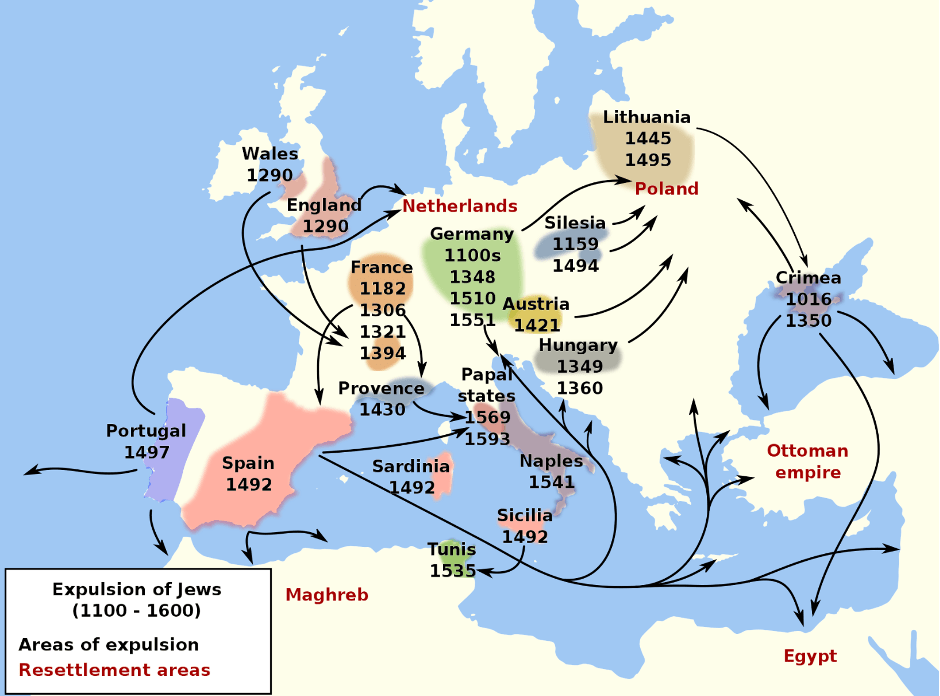

Again, to counter the “lachrymose” characterization, alluded to above, the pattern of the relentless Christian induced expulsions of Jewish communities is best illustrated by the Wikipedia map below. The depicted expulsions covering the period of 1100 – 1600, however, were preceded by several others such as in 415 from Alexandria ordered by Cyril, from Minorca in 418, in 612 from Spain, as mentioned above, and from Galilee in 629 by order of the Byzantine authorities.

It is illustrative that the antisemitic mind set resulted in expulsions of Jews in even the most unlikely time and place: in the U.S. in 1862. It was ordered by General Ulises Grant under General Order No. 11, to be implemented in Tennessee, Mississippi and Kentucky.

The antisemitic mentality permeating the entirety of Christian Europe through the ages can be illustrated by two apparently disparate examples. A painting at the cathedral of Sandomierz in Poland depicts ritual murders allegedly committed in that town by Jews on Christian children. The inscription above the painting reads filius apothecary ab infidelibus judaeis sandomiriensibus occisus (son of an apothecary, by infidel Sandomierz Jews killed). In addition, St Paul’s Church in the same town contains a different series of paintings including one in the chancel, depicting the torment of Jerzy Krassowski who was allegedly strangled by the Jews.

The other example of Catholic antisemitism is, of course, well known: the Spanish Inquisition which lasted well over 300 years. It is noteworthy that the last crypto-Jew or marrano indicted by that notorious institution was Manuel Santiago Vivar in Córdoba, as recently as 1818. The last to be accused for being a heretic for teaching deism, Cayetano Ripoll, was garroted in Valencia in 1826. The Inquisition was definitively abolished in 1834 by Royal Decree.

The insidiousness of antisemitism can even be identified in the arts. Modest Mussorgsky’s musical depiction of two Polish Jews, the rich Samuel Goldenberg and the poor Schmuyle, in his Pictures at an Exhibition masterpiece is more than a veiled allusion to Jewish greed and thirst for power. Shakespeare’s well known play The Merchant of Venice is of course a notorious case: Shylock, the Jewish merchant of that work is the epitome of the merciless usurer.

Ghettoes

After the Jews’s gradual and reluctant readmission to Europe after the 16th century, they were frequently confined to the so-called ghettoes, walled in restricted quarters with mostly poor living conditions.

The term, derived from the Italian gettare, which refers to the casting of metal, was first used in Venice in 1516, when authorities required Jews to move to the island of Carregio (the Ghetto Nuovo, new ghetto), across from an area where an old copper foundry was located (the Ghetto Vecchio, old ghetto). The ghetto in Venice was enclosed by a wall and gates that were locked at night. Jews had to observe a curfew, and were required to wear yellow hats and badges to distinguish themselves, a practice that the Nazis would later adapt in the 20th century. While the 1516 law creating the ghetto limited Jews’ freedom of mobility, to some degree it was less severe than policies elsewhere in Europe. Inside the confines of the ghetto, Jews had the autonomy to govern themselves and to sustain their own social, religious and educational institutions.

Though the term “ghetto” was first used in Venice, this was not the first instance of Jews being forced into segregated quarters. Compulsory segregation of Jews was common in medieval Europe, and these Jewish areas were later referred to as ghettos. The Lateran Councils of 1179 and 1215 advocated for the segregation of Jews. A ghetto-like community existed in 1262 in Prague, and by the 1400s became more common in other European cities from which they had not been expelled. In 1460 the Judengasse (“Jews’ Alley”) in Frankfurt was established.

In 1555, Pope Paul IV issued the “Cum nimis absurdum” proclamation, which required the Jews of Rome to live in separate quarters and also severely restricted their rights, including what businesses they could engage in. The purpose of this edict was to encourage conversion to Catholicism, an act that would serve as a ticket out of the ghetto. The ghetto made a clear distinction to the wider society between those who were “accepted” and those who were not. Though anti-Semitism was alive and well in the centuries that preceded this papal order, until 1555 the Jews of Rome had enjoyed freedom of movement. Under the new papal order, they were relocated to a crowded and unsanitary area that regularly was flooded by the Tiber River. While the ghetto was a place of squalor, the rest of the city was being built up with magnificent churches. This contrast allowed the authorities to highlight the differences between Jews and Christians, making it seem as though the destitute living conditions of the ghetto were the natural consequences of denying the divinity of Christ.

Though the ghetto was designed to segregate Jews, who were seen as a threat to Catholicism, it did not stop Jews and Christians from maintaining social and economic interactions; indeed Christians were allowed to enter the Roman ghetto during the day.

As we will discuss in what follows, in late 18th century, as part of a broader effort to spread liberty and equality, Napoleon sought to liberate the Jews from the ghettos of Italy. In one instance, in Padua, the French emperor even declared that the street where the Jews lived be renamed in order to remove the word “ghetto.” Nevertheless, the Jewish ghetto in Rome was hard to eliminate. Even though the gates were taken down in 1848 (due to protests by Roman citizens allied with Jews), the ghetto did not officially cease to exist until 1870, when Italy was unified and became a modern state. This period of Jewish emancipation— beginning in the late 18th century, continuing through the early 20th century — led to the dismantling of ghettos across Europe.

In the 1930s, Nazi Germany reintroduced ghettos in the areas under its control, adding the notorious laws that would restrict Jews’ basic human rights and laying the groundwork for future deportations and the horrors of the Holocaust.

The French Revolution and its Aftermath

The following section is quoted with some amendments from: “The Jews and the French Revolution” by Milo Lévy-Bruhl, 27 May, 2021

Before the Revolution, French Judaism was actually French Judaisms: there were at least two. The first, and numerically most significant, centered on the Jewish communities of the east, in Alsace and Lorraine, where three-quarters of the 40,000 lived. They were known as ‘German Jews.’ The other major Jewish settlement was in the south—a few thousand families living in and around Bordeaux and Bayonne—and its members were known as ‘Portuguese Jews.’ There were also Jews in Paris, largely former members of the two aforementioned communities, though their numbers were no more than a few hundred. Finally, there were Jews in Avignon and the Comtat Venaissin; but these areas were under the control of the Papal States until 1791, and Jews living there were not under French jurisdiction, but under the Vatican’s. These Jews, therefore, were known as ‘the Pope’s Jews.’

After the great expulsions of the 14th C., Jews returned to France following the military conquests of ancien régime France, or after the expulsion of the French and Portuguese that followed them. On arrival, they obtained lettres-patents which made them legal inhabitants of France, though not full citizens. They formally possessed almost no civil rights. Though their position in France was uniformly one of extreme precariousness, the different Jewish communities in pre-revolutionary France were characterized by markedly different levels of freedom and integration into the surrounding society. At one end of the spectrum, the Jews of Bayonne were almost perfectly integrated into the social fabric of the local bourgeoisie. At the other, the Jews of Alsace did not even enjoy freedom of movement within the region, and were still subject to frequent harassment and general persecution. As we will see, what to do about this vast difference in circumstance and station was a vexing question for French revolutionaries, but the fact remains: among the Jews — at least in the South of France — real social integration preceded any demand for political integration.

Political integration for French Jews had already been discussed well before the Revolution. The condition and the reformation of European Jewry often found itself at the heart of discussions during the Enlightenment, and at the heart of these discussions, often as not, was the figure of Moses Mendelssohn. A central figure in the German Enlightenment, French revolutionaries considered Mendelssohn’s life a topic of significant importance—important enough to warrant a 1787 biography, On Moses Mendelssohn and the Political Reform of the Jews, authored by Mirabeau, a revolutionary figure of some importance.

That same year, the Royal Society of Sciences in Metz chose the following prompt for its famous competition: “Is there a way to make the Jews more useful and happier in France?” Among the various different answers set forth in response, one of the most remarkable is that of the Abbé Grégoire, who pleaded for the physical, moral, and political regeneration of the Jews.

Then, in 1789, in the space of just a few months, the Estates-General proclaimed itself the National Constituent Assembly, the Bastille was stormed, the aristocracy was abolished, the clergy’s property was expropriated, and the Declaration of the Rights of Man was adopted.

The Assembly had declared human rights apply to all—but what of the rights of a citizen? What of the men to whom rights had long been denied? What of Protestants, actors, and executioners? What of Jews? It was in this manner that, for the first time in France, the question of citizenship for Jews was posed. It divided the chamber immediately.

Among the defenders of Jewish rights were, as previously mentioned, the Count of Clermont-Tonnerre, and of course the Abbé Grégoire. The former’s speech on the topic is a classic discourse on the subject of French Jews. A justly famous sentence sums up the Count’s position: “All must be denied to Jews as a nation; all must be given to Jews as individuals.” His logic is simple: The Jews had to abandon completely their own laws for the laws of France. Their religious freedom would be guaranteed within the limits of national law. In exchange, they would be granted the full rights of a French citizen.

Contrary to what one might think, despite the strength of Clermont-Tonnerre’s argument, the partisans of Jewish emancipation failed to achieve their goals. On December 24th, at the close of the debates on Jewish rights, the Assembly decreed that “…the non-Catholics will be able to be electors, and will be eligible, to the degree that they are able, for all civil and military employment, as any citizen is . . . all the above applies without prejudging anything regarding the Jews, on whose status the National Assembly reserves the right to pronounce itself at any time.” Everything remained to be done.

When, a few weeks after the vote of December 24th, the ‘Portuguese Jews’ came before the Assembly to file a petition, the revolutionaries took it as an opportunity: In January of 1790, they were granted citizenship.

As for the ‘German Jews?’ It took nearly two years of debate and cunctation before, in September of 1791, just a few days before its dissolution, the National Assembly recognized citizenship for all French Jews. But there was an implicit quid pro quo in the deal: In order to secure citizenship, ‘German Jews’ had to forgive any debts owed to them by French Catholics. Why? To prove their regeneration—which, for them, was not exactly miraculous.

As to Italy’s political fragmentation at the time, this debate was appropriately diffuse. As early as 1778, Leopold II made provisions for the Grand Duchy of Tuscany, and these provisions allowed Jews to participate in local political life there. In Mantua and Trieste, the Habsburgs and their 1782 Edicts of Tolerance, allowed Jews to practice manual trades and access universities. Meanwhile, in the Duchy of Savoy, the Republic of Venice, and the Papal States, anti-Enlightenment positions influenced a restrictive policy toward Jews marked by the stiffening of anti-Jewish legislation, and the reinforcement of ghettoization. The Napoleonic Campaign of 1796 was to change everything for Italian Jews.

Following it, the ghettos were opened, and a period of unprecedented Christian-Jewish fraternization commenced. But the jubilation of Italian Jews was short-lived. From 1799 onward, counter-revolutionary violence manifested a distinct anti-Semitic streak, marked by horrific massacres, most notably in Siena. The debate on emancipation came to an abrupt halt. It wouldn’t resume until 1807, with Napoleon’s summoning of the Jews to the Grand Sanhedrin, the Supreme Court of the Jewish people in Biblical and Talmudic times, but which had been disbanded centuries earlier due to persecution.

The Grand Sanhedrin was convened by Napoleon, and brought together representatives of rabbis and other Jewish notables from across his empire. This gave the decisions made there a European dimension and, for the Jews of Germany and Italy, gave Napoleon a heroic dimension. He was glorified as ‘the new Moses,’ who had brought equality to his conquered lands. In France, however Napoleon’s desire to organize Judaism also led to important legal regressions. In 1808, the Jews of Alsace were subjected to an unusually onerous decree—nicknamed, aptly enough, “the infamous decree”—which required them to obtain a special government dispensation in order to practice commerce, and forbade them, and them alone, from the possibility of avoiding conscription in the army. It also canceled a large part of debts owed to them by Christians. Many small Jewish moneylenders were reduced to penury with a pen stroke.

Oddly enough, it was the Restoration monarchy that decided not to renew this ‘infamous decree’ in 1818. The last vestiges of discrimination against French Jews disappeared under the July Monarchy, when the government of Louis-Philippe decided to take responsibility for the salaries of rabbis, as it had for other religions. It marked the beginning of what historians regard as the Golden Age of French Judaism.

The end of this Golden Age came with the anti-Semitic rumblings of the late 19th C, a time during which the memory of the revolution loomed large in the minds of both the Jews and their rivals. It was when Drumont’s La France juive was published—a book which begins, famously, with the assertion, “The only group the Revolution has protected is the Jews.” Meanwhile, for a majority of French ‘Israelites,’ as they were known, the response to this anti-Semitism was to glorify the heritage of the Revolution that had conferred them their rights. This was the case, for example, in the Jewish response to the Dreyfus Affair, when Jews hoped Revolutionary Ideals would prevail, and put an end to Dreyfus’ exile in a penal colony. For many Jewish intellectuals — and for community leaders as well — the official recognition of Dreyfus’ innocence was proof of the endurance and ultimate durability of revolutionary emancipation.

The 19th and 20th Centuries

Let me proceed with a bit of history in what concerns the origins of the state of Israel. As discussed above, European Jewry had emerged in the late 18th century from a long period of suppression and confinement. Although being encouraged by the monarchical powers of that time to join in Europe’s gentile society, this integration was hampered by long-engrained prejudices and Christian religious antisemitism. It forced many Jews during the 19th century to convert to either Protestantism or Catholicism in order to secure an entry into the society at large. I can cite several examples of those who followed that path: Heine, the notable German poet, Mendelssohn, Mahler, and Offenbach, famous German and French composers, Disraeli, British prime minister, Marx, German philosopher, and many other famous Jews.

Typical example of the quandary facing the Jews in the 19th centuries is the case of the brilliant German poet, writer and literary critic Heinrich Heine. On 28 June 1825, he was baptized a Lutheran Christian in Heilingenstadt. The Prussian government had been gradually restoring discrimination against Jews. In 1822 it introduced a law excluding Jews from academic posts and Heine had ambitions for a university career. As Heine said in self-justification, his conversion was to be “the ticket of admission into European culture”. In any event, his conversion, which was reluctant, never brought him any benefits in his career. A quarter of a century later, Heine declared: “I make no secret of my Judaism, to which I have not returned, because I never left it.”

In spite of these conversions and the notable accomplishments of these Jews and of those who did not convert, a gradual recrudescence of antisemitism occurred towards the waining years of the 19th century fostered, especially in France, by the Catholic church and its adherents, culminating with the notorious Dreyfus Affair.

This dispiriting development inspired a Zionist movement among the leaders of the Jewish intelligentsia of that time. The conclusion among these thinkers was that there was no viable place in Europe for the Jewish people and that a land of their own, elsewhere, had to be found. The obvious choice was the ancestral land of the Jews, Israel.

In 1896, Theodor Herzl, a Jewish journalist living in Austria-Hungary, published the foundational text of political Zionism, Der Judenstaat (“The Jews’ State” or “The State of the Jews”), in which he asserted that the only solution to the “Jewish Question” in Europe, including the growing anti-semitism, was the establishment of a state for the Jews. A year later, Herzl founded the Zionist Organization, which at its first congress called for the establishment of “a home for the Jewish people in Palestine secured under public law”. Proposed measures to attain that goal included the promotion of Jewish settlements there, the organization of Jews in the diaspora, the strengthening of Jewish feeling and consciousness, and preparatory steps to attain necessary governmental grants.

It is worth mentioning the Uganda Scheme, a proposal, near the turn of the century, by British colonial secretary Joseph Chamberlain (not to be confused with Neville Chamberlain, British prime minister at the start of WWII) to create a Jewish homeland in British East Africa. It was presented at the Sixth World Zionist Congress in Basel in 1903 by Theodor Herzl, who saw it as a temporary refuge for Jews to escape the rising antisemitism in Europe. The proposal faced opposition from both within the Zionist movement and from the British Colony.

The objective of creating a Jewish haven in Palestine received a resounding support by the Balfour Declaration, a 1917 statement from British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to Lord Rothschild, a Jewish British leader, supporting the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine. This letter, which later became a key political foundation for the state of Israel, also stated that nothing should be done to prejudice the civil and religious rights of Palestine’s existing non-Jewish communities. The declaration was a significant political victory for Zionism, and had a lasting and contentious impact on the Middle East.

There is one more all encompassing aspect to the antisemitism permeating the interbellum period. It is the identification of Jews with communism. It goes back to the Russian Revolution that toppled the Tsars at the end of WWI. The Germans, very soon after, and encouraged by the so-called White Russians who had fled from Russia to Germany, attributed the Russian Revolution to an alleged Jewish Bolshevism, an anti-communist conspiracy theory. It purported that that revolt was a plot to destroy Western civilization and, eventually, served the Nazis as an ideological justification for the invasion of the USSR and the Holocaust.

That canard then also fed the ideology of the German American Bund in the U.S. It provided the basis for the antisemitism of the American State Department and the politics embraced by high level functionaries, such as Breckenridge Long, of barring Jews from accessing the U.S. during WWII.

I am suggesting that the rejections for immigration to the U.S. suffered by my family, especially at the embassy in Madrid in 1941, were elicited by that spurious identification of Jewishness with a purported Communist allegiance.

My father, Erich, had a distinct so-called Jewish physiognomy. He was somewhat swarthy, dark eyes, and had an aquiline nose. I can well surmise the American embassy functionary, with whom Erich had to deal, reacting with a distorted identification of a highly educated German Jewish fugitive from the Nazis, with that of a Communist, and possibly even a Bolshevik agent. So, we as Jews, had to face a multiple jeopardy: Nazi persecution based on racism and “Judeo-Bolshevism” (as recently cited by Jochen Hellbeck in “World Enemy No1”) and American anti Communist-driven antisemitism.

After the end of WWI German accusations against Jews blaming them for the defeat of Germany during that war started to surface. Very soon, in the 1920s, with the rise of the Nazi movement, anti-Jewish propaganda saw a dramatic escalation culminating with Hitler’s brazen Machtergreifung (seizure of power) in early 1933.

What followed needs not to be analyzed herein: the Holocaust of six million Jews.

This outcome had not even been predicted by the founders of Zionism. Once the horrific magnitude of this genocide had become public knowledge, after the end of WWII, the implementation of the Balfour Declaration became imperative and received wide support among the nations of the recently created United Nations organization.

The Creation of Israel and its Aftermath

The Palestine Mandate was a British administrative government of the region of Palestine from 1923 to 1948, following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the end of World War I. Established by the League of Nations, it was tasked with preparing the area for self-governance, with a key, controversial requirement to facilitate the creation of a Jewish national home alongside safeguarding the rights of the existing Arab majority. This mandate period was characterized by rising tensions and conflict between the two communities, which eventually led to the United Nations recommending the mandate’s termination, the partition of Palestine and the subsequent establishment of the State of Israel.

On 29 November 1947, the United Nations General Assembly voted 33 to 13, with 10 abstentions and 1 absent, in favor of a modified Partition Plan. The map representing this Plan is shown in the next page.

The Jewish community in Palestine accepted the Partition, although reluctantly, whereas the Arab states rejected it roundly.

At midnight on 14 May 1948, the British Mandate expired, and Britain disengaged its forces. Earlier in the evening, the Jewish People’s Council had gathered at the Tel Aviv Museum (today known as Independence Hall), and approved a proclamation, declaring “the establishment of a Jewish state in Eretz Israel, to be known as the “State of Israel”. The 1948 Arab–Israeli War then began immediately with the invasion of, or intervention in, Palestine by the Arab States on 15 May 1948.

Armies of Egypt, Transjordan, Syria, and expeditionary forces from Iraq entered Palestine, taking control of the Arab areas and attacking Israeli forces and settlements. A 10-months of fighting took place mostly on the territory of the British Mandate and in the Sinai Peninsula and southern Lebanon.

By the end of the war, the State of Israel controlled all of the area that the UN had proposed for a Jewish state, as well as almost 60% of the area proposed for an Arab state, including Jaffa, Lydda and Ramle area, Upper Galilee, some parts of the Negev, the west coast as far as Gaza City, and a wide strip along the Tel Aviv–Jerusalem road. Israel also took control of West Jerusalem, which was meant to be part of an international zone for Jerusalem and its environs. Transjordan took control of East Jerusalem and what became known as the West Bank, annexing it the following year. The territory known today as the Gaza Strip was occupied by Egypt.

Expulsions of Palestinians, which had begun previously, continued during the Arab-Israeli war. Hundreds of Palestinians were killed in multiple massacres, such as occurred in the expulsions from Lydda and Ramle. These events are known today as the Nakba (Arabic for “the catastrophe”) and were the beginning of the Palestinian refugee problem. A similar number of Jews moved to Israel during the three years following the war, including 260,000 who migrated, fled, or were expelled from the surrounding Arab states.

It is worth pondering the course of history if the Arabs had accepted the Partition of Palestine. I can venture at least two possible outcomes: a) a two-state peaceful coexistence after some mutually agreed upon boundary adjustments between the two states, and b) an initial fraught coexistence followed by repeated military confrontations which would, in the end, have culminated with an Israeli takeover of the entire territory.

What actually transpired since the 1948 founding of Israel is essentially equivalent to that second alternative. After a series of wars with its Arab neighbors, especially the Six Day War (June 1967) which was fought between Israel and Arab neighbors Egypt, Jordan, and Syria to which Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Algeria, and others also contributed troops and arms to the Arab forces. Following the war, the territory held by Israel expanded significantly: The West Bank (including East Jerusalem) from Jordan, Golan Heights from Syria, Sinai and Gaza from Egypt. Israel agreed on the return of the Sinai peninsula to Egypt which was completed in 1982.

The Wikipedia map below shows the present boundaries of Israel, including the areas that, in principle, were left in Arab hands but which, de facto, are under Israeli control, namely the West Bank and the Gaza strip.

It must be recognized as remarkable the fact that Israel has been able to prevail in all its wars against the combined forces from several Arab states.

Throughout its history, however, Israel has treated those Arabs living within its boundaries as second class citizens. This situation led to increasing frictions between the Arab and Jewish populations, resulting in the so-called intifadas, uprisings by Palestinian Arabs — in both the Gaza Strip as well as the West Bank — against Israel. It culminated with the war that began on 7 October 2023, when Hamas and other Palestinian militant groups launched a savage surprise\ attack on Israel, in which 1,195 Israelis and foreign nationals, including 815 civilians, were killed and 251 were taken hostage. A massive reprisal against Hamas by Israeli forces ensued resulting in tens of thousands of dead and wounded Palestinians in the Gaza Strip, and the devastation of that territory. As of this writing (October 2025), there is a cease fire in effect.

In addition to the Gaza war, there have been increasing encroachments and attacks by Israeli settlers on lives and property of Palestinians of the West Bank which had been established, together with the Gaza Strip, as Palestinian territory (see map above).

Concurrently, Israel has been engaged in military confrontations with Iran and its militant supporters, in addition to Hamas, such as Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthi’s in Yemen.

All of the above cited events have taken place under a right wing fundamentalist Israeli government headed up by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

The international community, with the exception of the United States, most recently under the second Trump administration, has vigorously condemned Israel’s handling of the Gaza War and, to some extent, isolated that country in its interactions with that community.

Israel had been created as a secular nation with a quasi-egalitarian society, as a Jewish state. Under David Ben-Gurion, its first Prime Minister and primary national founder of Israel, a socialist regime established principally centered around the kibbutzim, collective farms or settlements owned by its members. The very character of this nation, however, has undergone a gradual and insidious change. At its foundation it included a small fraction of Jewish fundamentalists called the Haredim, ultra-Orthodox Jews who follow a strict interpretation of Jewish law and tradition, characterized by their distinctive dress and a commitment to living separate from modern secular society to devote themselves to prayer and study. Originating in 19th-century Europe as a reaction to modernization, their community prioritizes Torah learning and traditional values, with many living in communities isolated from the outside world.

There were about 40,000 Haredim in Israel at its foundation. That number now exceeds 1.5 million, a significant fraction of the total Jewish population of Israel. They enjoy special status, among which they have been exempt from military service. This was originally implemented by Ben-Gurion most probably under the assumption that a small minority of such ultra-orthodox cohort would have no major political or societal effect on the life of Israel. That assessment proved to be illusory. Furthermore, this development was accompanied by a concomitant growth of a right wing political fraction with intense chauvinistic and messianic undertones, bent on recreating a purportedly divinely ordained biblical Eretz Israel which, in its latest incarnation consists of the present State of Israel, which includes the modern-day country, the West Bank, Gaza, and the Golan Heights. The implication of this extremist view is that this entire territory should be the exclusive abode of the Jewish people and it appears to be the implicit objective of the current, theocratically infused, Israeli administration.

The preceding summary of Israel’s history as a Jewish state raises the inevitable question as to its validity. Can a state be based on a two tier system within which there is a form of “apartheid” wherein there is a dominant population defined by ethno-religious roots versus another with lesser rights? The negation of this premise has now become the stimulus for antisemitic and generalized anti-Israel pronouncements. I would like to submit that Israel does not stand alone in such societal, political and religious segregation. Here are three examples of Muslim nations that proclaim such dichotomy: Iran whose official denomination is the “Islamic Republic of Iran”, Saudi Arabia which defines itself as a “Sovereign Arab Islamic state”, and the “Islamic Republic of Pakistan”, all major nations where Muslims enjoy major privileges and rights.

I do not want to imply my endorsement of that type of discrimination, neither in the Muslim world nor in Israel. About the latter country, however, the history, in my view, is more complicated. The State of Israel was created to a large extent as a special case, a worldwide attempt at a redress and compensation for the horrific suffering of the Jewish people at the hands of the Nazis, and to provide a safe haven to that people after centuries of persecution. It was under the latter rubric that for many years I fully endorsed its right to exist although recognizing the disruption and hardships exerted on the Arab population.

And then, after all, we should remember that at the founding of Israel in 1948 the Arab world rejected the two-state solution that the United Nations had approved causing the start of hostilities and the so-called Nakba. It is ironic that the implementation of that international decision is now considered by the Arab world as a sine qua non solution to the Palestinian problem, at the same time as it is being rejected by the current right-wing Israeli administration bent, as mentioned above, at the takeover of the entire Palestinian territory.

The start of the Gaza War, provoked by the brutal attack on Israel on 7 October 2023, when Hamas and other Palestinian militant groups launched a surprise attack on Israel, in which 1,195 Israelis and foreign nationals, including 815 civilians, were killed and 251 were taken hostage followed, in turn, by the retaliatory war inflicted by Israel on both the terrorists and the Palestinian civilian population has created an enormous degree of human suffering on the latter. It is estimated that well over 60,000 people (including Hamas fighters) have perished in the Gaza Strip since the start of the hostilities. This disregard for human life has been compounded by the thorough destruction of properties and infrastructure of all the urban centers within the Gaza strip. Furthermore, the Arab population of the West Bank has been subjected to wanton harassment and persecution by the Jewish settlers who gradually and systematically and for many years have encroached on that territory.

This degree of collateral harm to the civilian population of Gaza cannot be justified, in my opinion and in that of a majority of people around the world, including many in the Jewish community. It is becoming a stain on the state of Israel which is providing fodder to the proliferation and escalation of worldwide antisemitic sentiment. Israel is, through its own extreme brutality, degrading itself having abandoned one of the most salient characters of Judaism, namely its humanitarian approach to the human experience. The present Israeli government has been taken over by a theocratic chauvinism that parallels that of several Muslim countries such as Iran and Afghanistan. Obviously, the support of that regime and its actions by the Trump administration only compounds its degradation. In this latter context, the apparent opposition to antisemitic demonstrations on university campuses is a thoroughly self-serving and hypocritical smokescreen by the Trump cabal to blackmail and coerce those institutions to adhere to the ideological constraints imposed by that kakistocracy. This phony opposition to antisemitism should not be welcome by the Jewish community.

It will take many years of a sane and secular Israeli regime to undo de staggering damage that the present cast of Israeli extremists is causing on the international standing of Israel by providing justification for the general vilification of Jews, undermining the laudable efforts of the segment of gentile society opposed to antisemitism, and not the least, dividing the Jewish community.

Last but not least, as a secular non-practicing Jew by descent from uncountable generations of Ashkenazi Jews, I am distraught at the actions, intentions and creed of the State of Israel in its present extremist theocratic, intolerant and chauvinist incarnation. I dissociate myself from that government and its followers and fervently hope for its demise and, for Israel at large, to a return to humanitarian and humane sanity.

The following addendum was added post facto.

Judaism is not another religion

What I instinctively knew has surfaced as a blindingly clear epiphany: Judaism is not just another religion like Christianity is. This is best understood through the following statement of fact: You can be a secular Jew but you cannot be a secular Christian. Or, similarly and more emphatically: You can be an atheist Jew but you cannot be an atheist Christian.

I believe that the above differentiation contributed to the proliferation, persistence and metamorphosis of antisemitism. The fluctuations between religious and racial antisemitism throughout the ages can, to a significant degree, be attributed to Christian confusion engendered by that distinction.

We Jews belong to an outlier cohort: an ethno-religious entity united by descent from a hundred or more generations of Jews who shared, for most of that time, a mostly common religion.