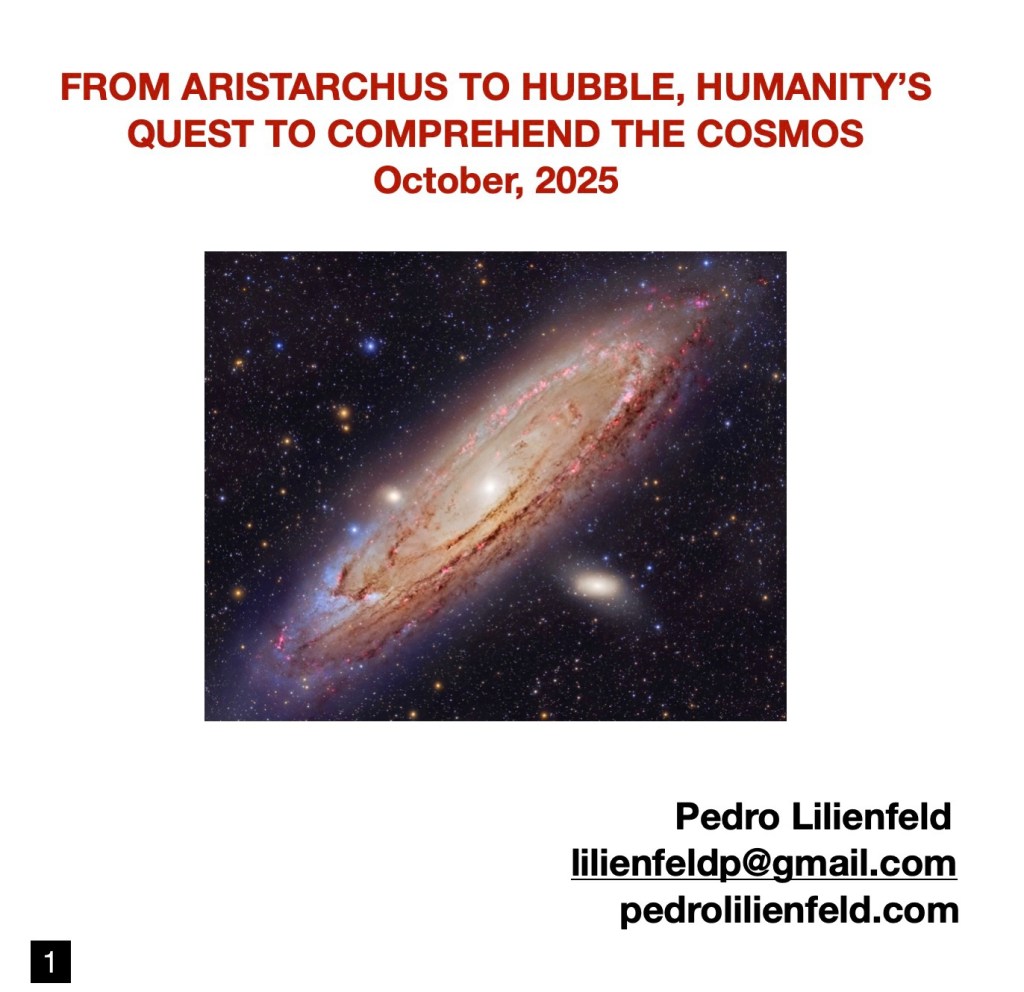

Humanity’s Quest to Comprehend the Cosmos

Introduction

This is a written complement to a set of slides presented at a class with the above title given in October of 2025 within the framework of the Lexington Community Education. These slides follow this writing (or click here to view them immediately).

The contents of this class are to be considered an attempt at summarizing a vast subject bracketed by the breakthroughs of the Hellenistic Greek insights between about 300 BCE and 100 BCE, and the Hubble/Lemaître discovery in the 1920s.

It should be emphasized that the advancements of astronomy during that over two millennia period were anything like a monotonic progression. They often followed a meandering as well as sometimes petrified path, obstructed by long-held beliefs and prejudices. In this context it is worth considering the perspicacity that the author Arthur Koestler evinces in his idiosyncratic 1959 treatise The Sleepwalkers whose title reflects that convoluted path.

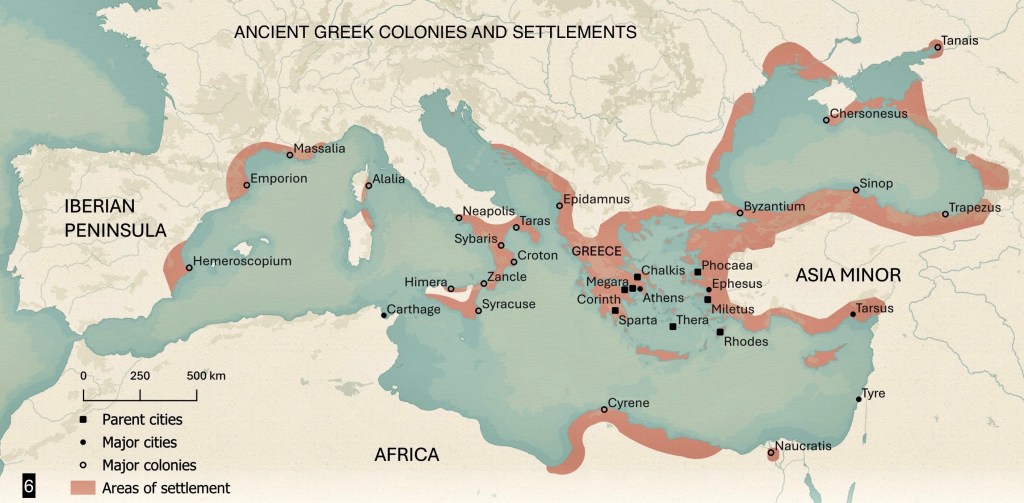

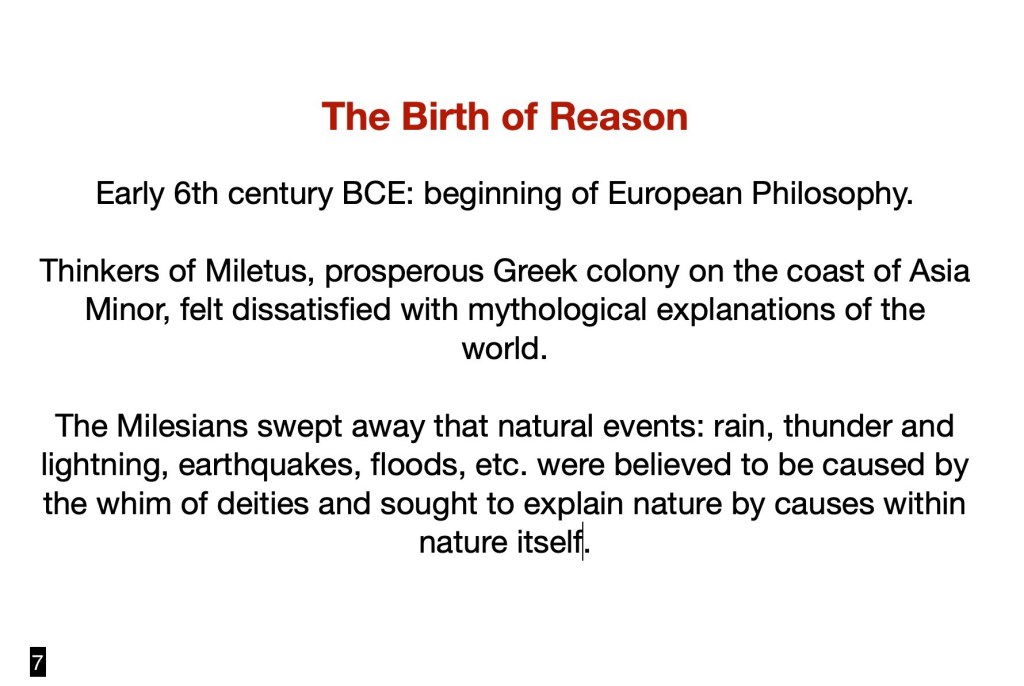

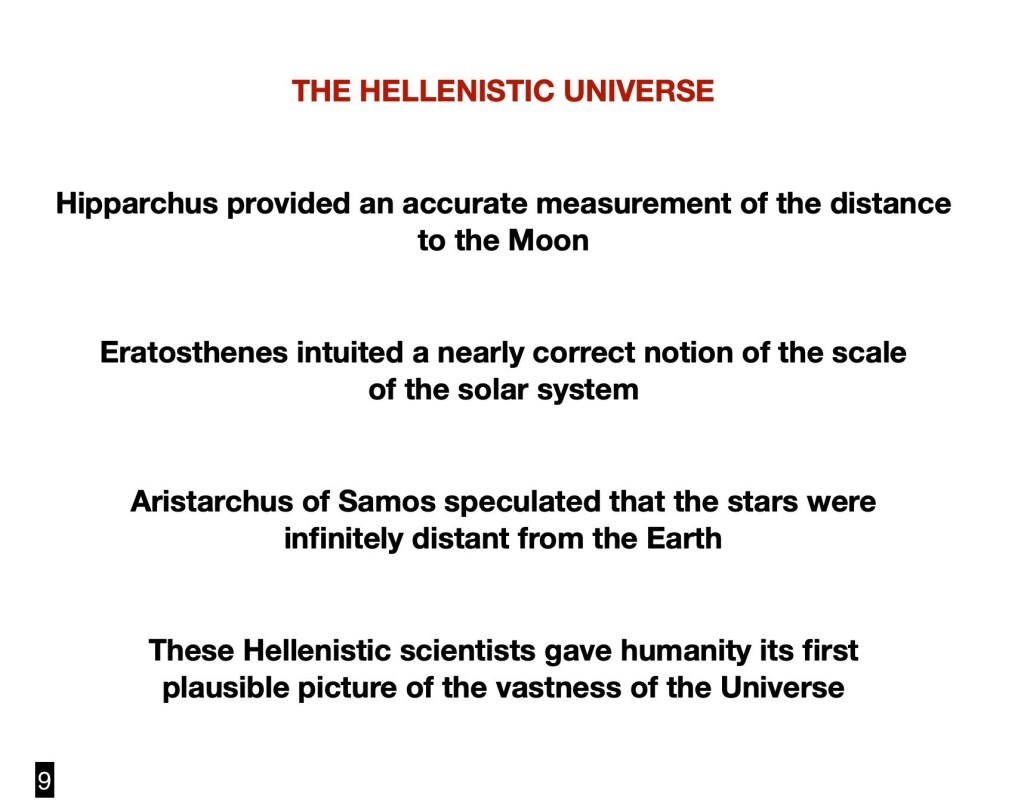

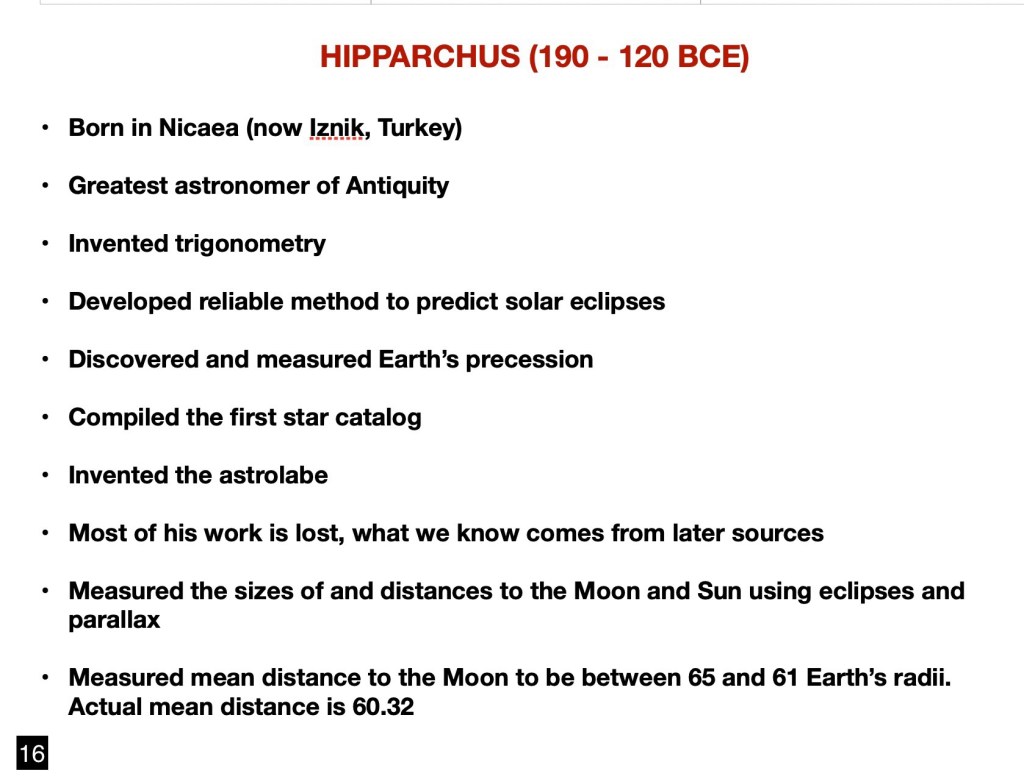

Antiquity

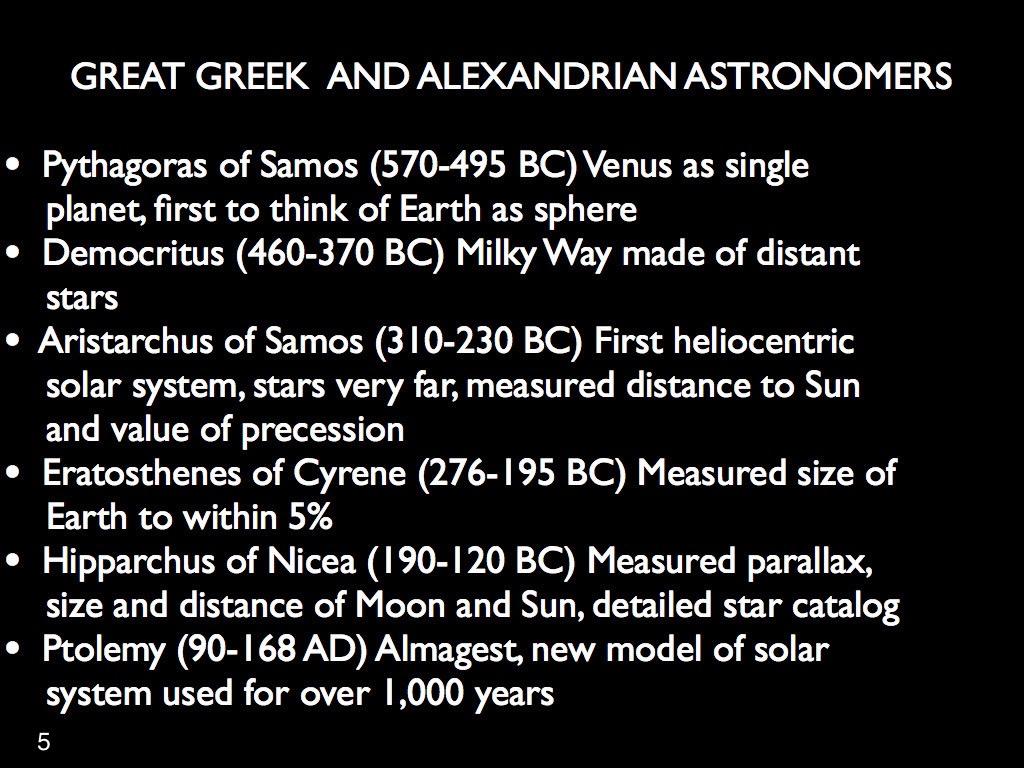

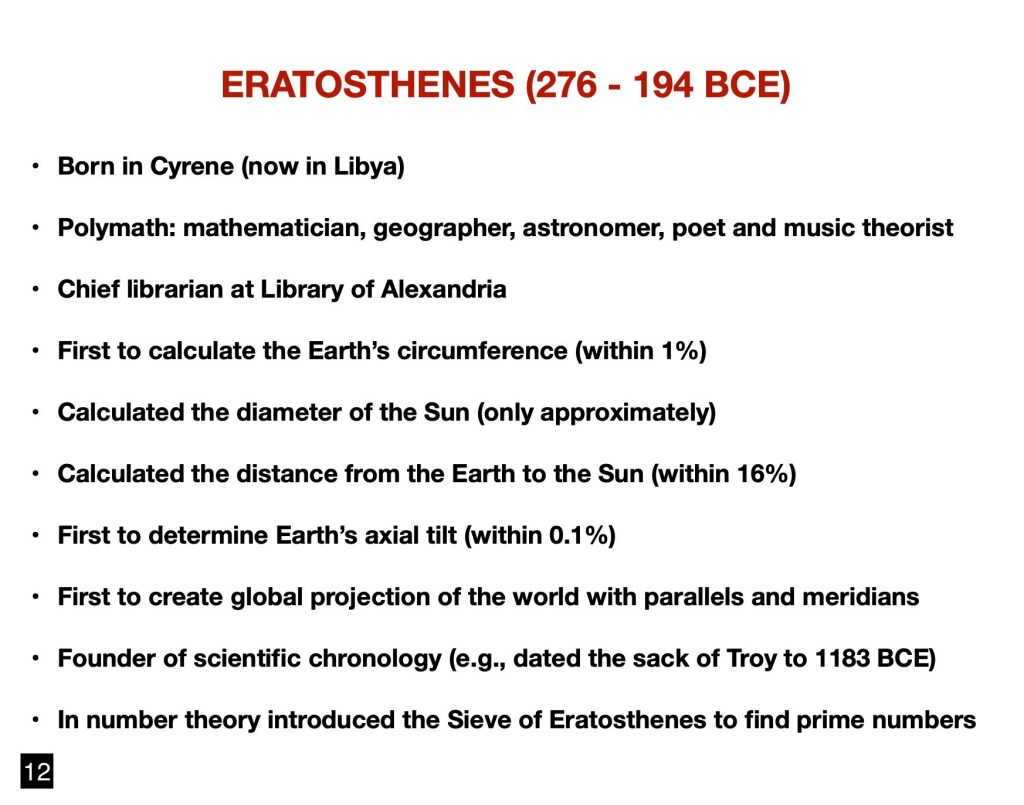

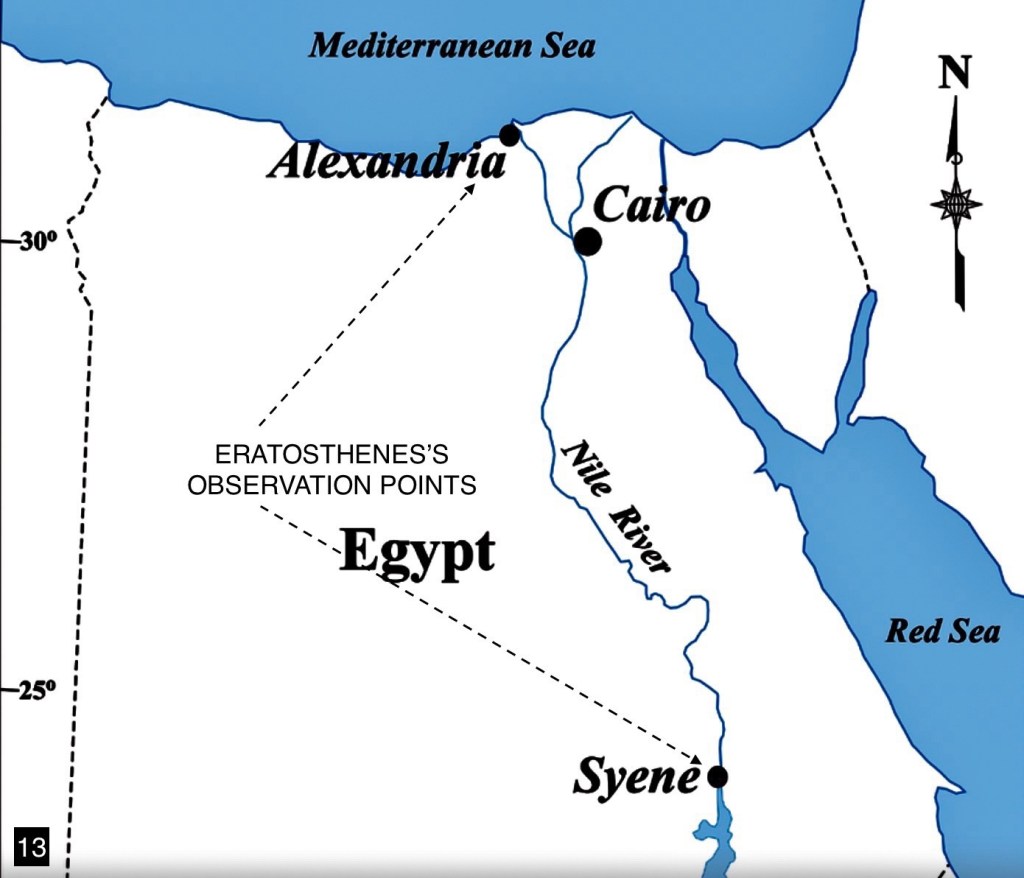

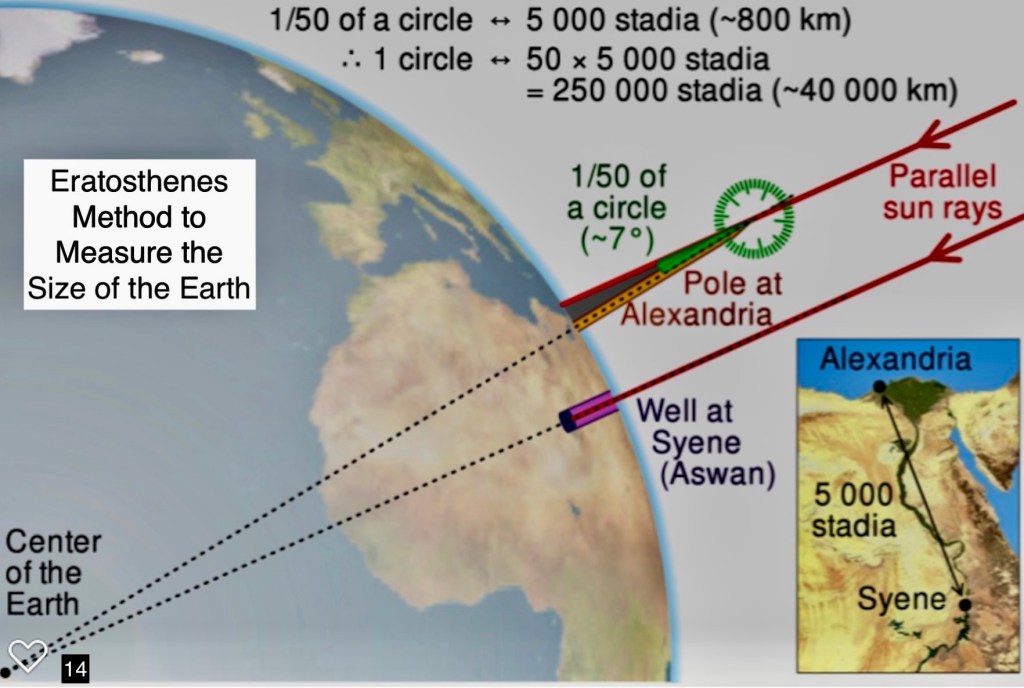

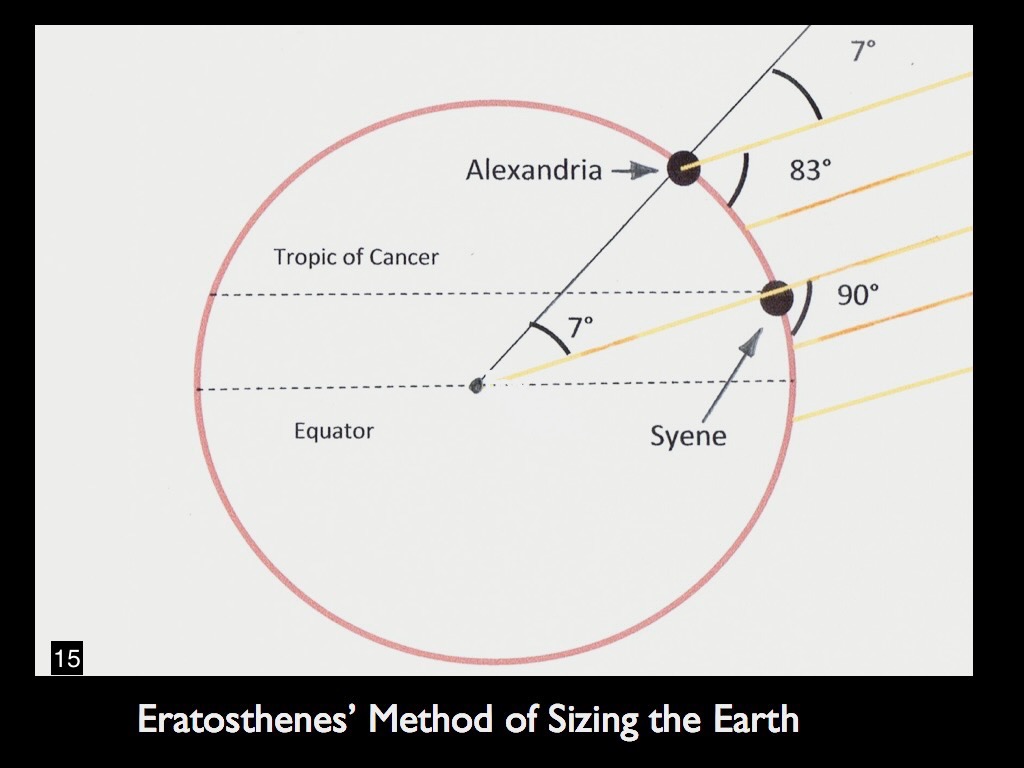

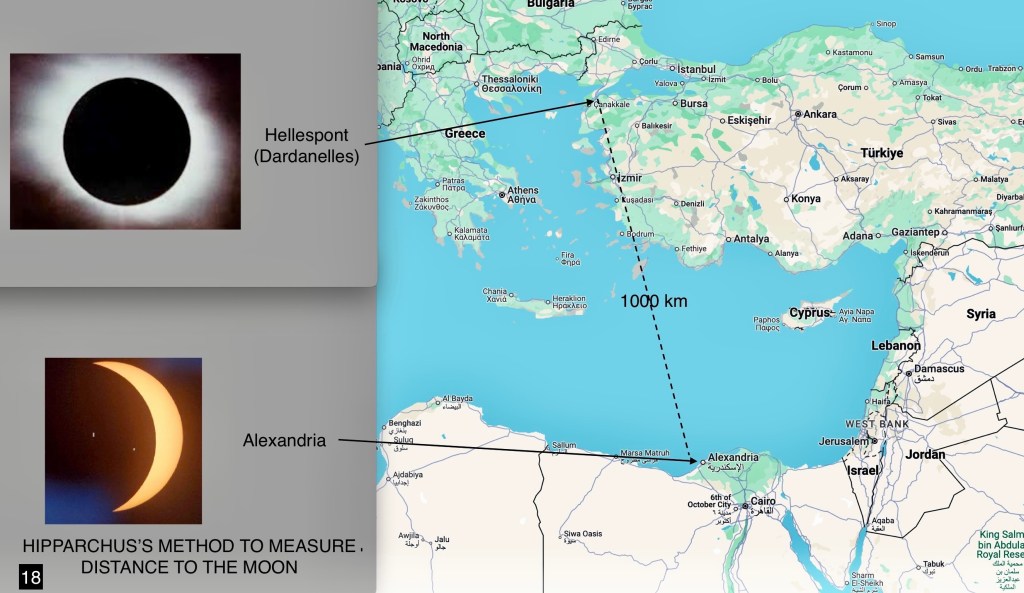

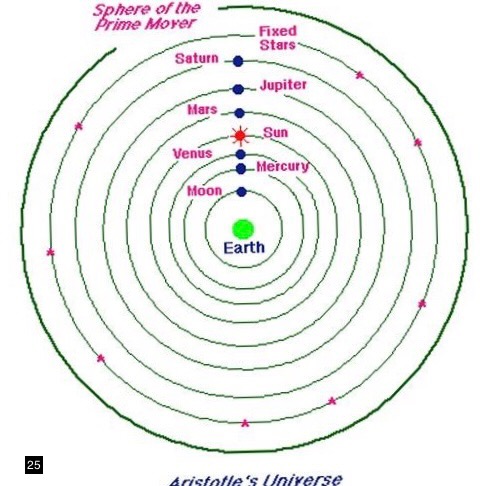

I have chosen to begin this summary with the very first truly scientific treatment of astronomy which was achieved in the Hellenistic world. I am referring to the achievements of what I call The Three Musketeers of Ancient Greek astronomy: Aristarchus of Samos, Eratosthenes of Cyrene and Hipparchus of Nicaea. Their contributions were to be foundational to future developments. To summarize, limiting their accomplishments to the most salient: 1. Aristarchus formulated the first heliocentric solar system, preceding Copernicus by over 1,800 years; 2. Eratosthenes measured the size of the Earth within about 1% of its true size; and 3. Hipparchus determined the size of the Moon and the Sun as well as the distance to the Moon within a few percent, using the method of parallax which is still applied at present to measure the distances within our Milky Way galaxy. Thereafter, however, further progress can be viewed as having derailed. Aristarchus’s heliocentrism was disregarded as the authoritative Aristotle predicated a rigid and dogmatic geocentrism which was to persist for the next millennium and a half in the western world, principally because it was embraced by the Catholic church.

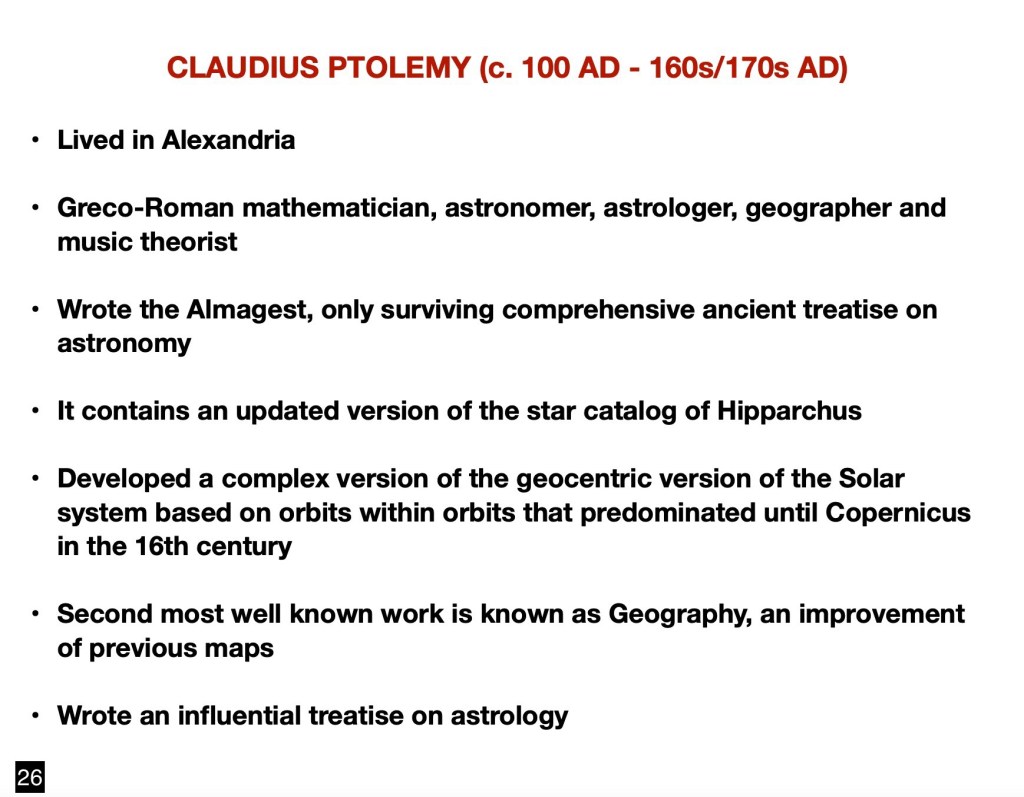

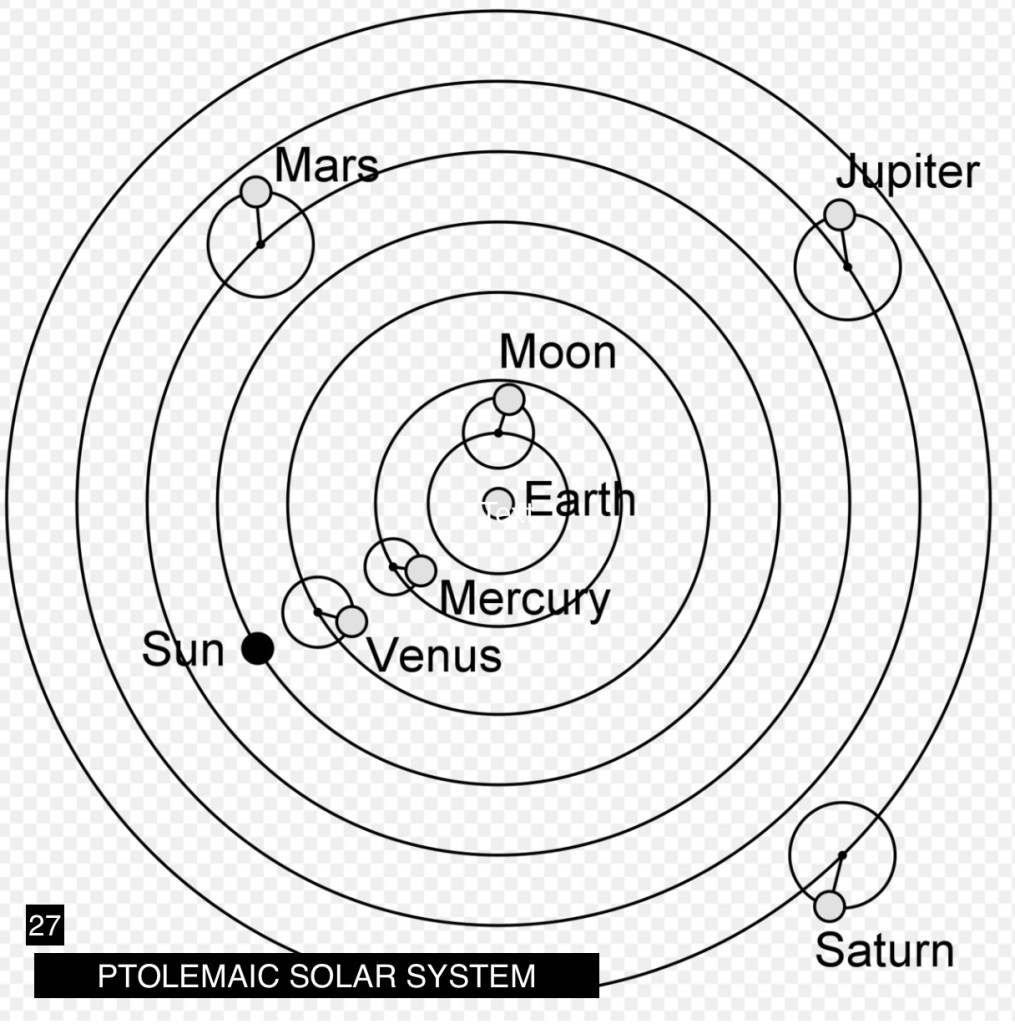

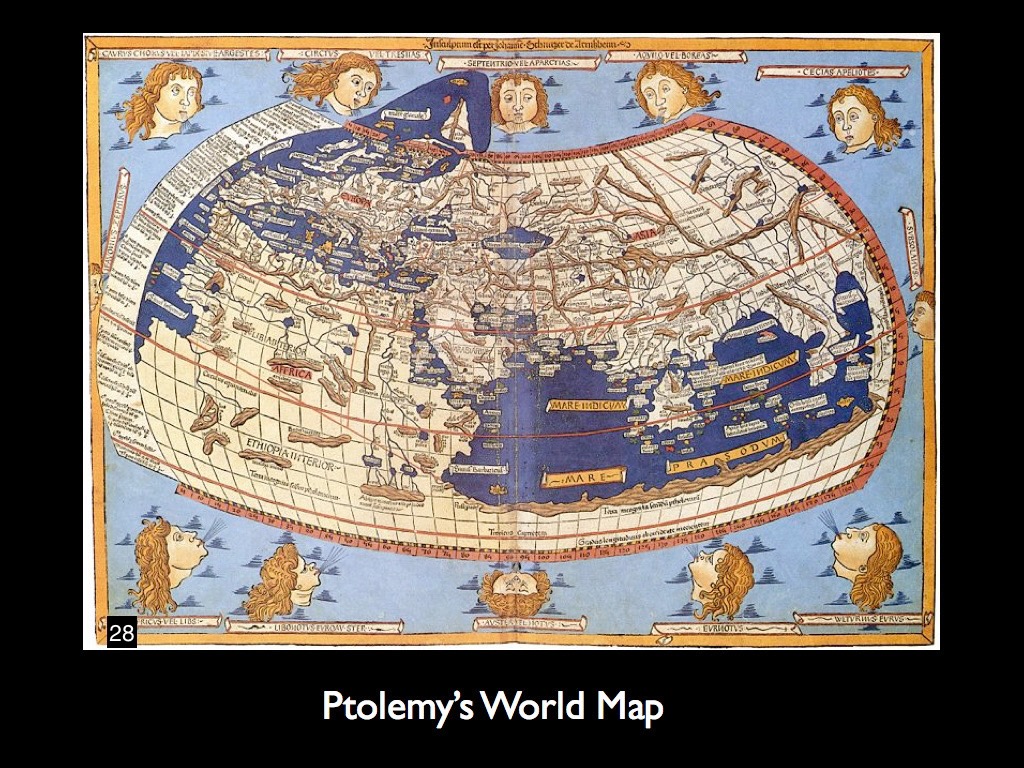

Problems arose, however, when astronomers in the Greco-Roman world found that the motions of some of the planets disagreed with the Aristotelian model of concentric circles centered on the Earth. This was especially obvious in the case of Mars which appeared to regularly reverse course. Thus, in order to preserve the sacrosanct centrality of the Earth, Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century devised what can only characterized as a contrived modification of the simple geocentric Aristotelian model. It consisted of the addition of secondary planetary orbits, called epicycles, such that each planet and the Moon moved in composite orbits within orbits. This was, in retrospect, a convoluted solution unrelated to reality.

This Ptolemaic system, however, predominated with minor variations for the next millennium. This is a classical example of what the eminent 20th century physicist Steven Weinberg identified as a view of “what ought to be” rather than “what is”: clinging to geocentrism rather than accepting the reality of heliocentrism. The idea of “dethroning” the Earth from an illusory privileged place in the cosmos was to be anathema until the 16th century, and even then it remained a heresy within the Catholic realm until the early 19th century.

The Middle Ages

With the collapse of the Roman empire in the 5th century we see the period of social instability of the early Middle Ages that precluded any productive pursuit of astronomy and the sciences at large. The first reawakening occurred in the Middle East during what is now known as the Islamic Golden Age, from the 9th to the 12th centuries. A salient contribution of the Moslem savants of that period was to act as preservers and conduits of the Greek Hellenistic knowledge, refining and complementing that body, questioning some of Aristoteles’s and Ptolemaic ideas and preparing for the advent of the Western Renaissance intellectual opening.

Beginning in the 10th century, a tradition criticizing Ptolemy developed within Islamic astronomy, which climaxed with Ibn al-Haytham’s

Al-Shukūk ‘alā Baṭalamiyūs (“Doubts Concerning Ptolemy”). Several Islamic astronomers questioned the Earth’s apparent immobility, and centrality within the universe. Some accepted that the Earth rotates around its axis, such as Abu Sa’id al-Sijzi (d. c. 1020). According to al-Biruni, al-Sijzi invented an astrolabe based on a belief held by some of his contemporaries “that the motion we see is due to the Earth’s movement and not to that of the sky.” That others besides al-Sijzi held this view is further confirmed by a reference from an Arabic work in the 13th century which states: According to the geometers [or engineers] (muhandisīn), the Earth is in constant circular motion, and what appears to be the motion of the heavens is actually due to the motion of the earth and not the stars.

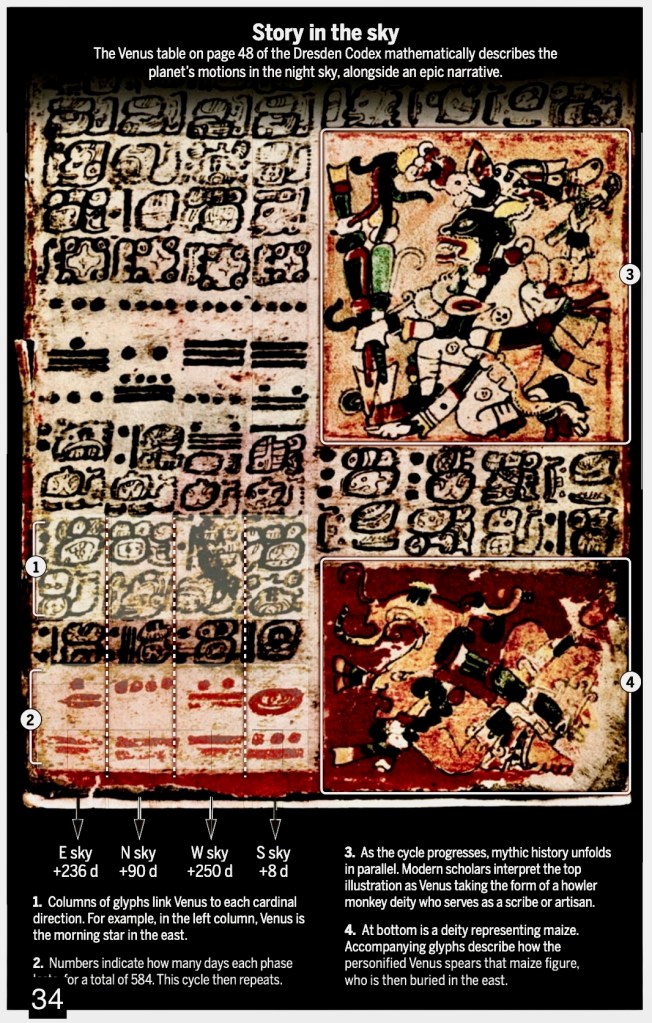

Outside of the Western realm it is worth mentioning the status of astronomy within such civilizations as those of China, India and Maya. Observations of the Cosmos in all of them was motivated principally by two objectives: tracking the calendar mainly for agricultural purposes, and the identification and predictions of omens and the preparation of horoscopes. Astrology was the common denominator driving the pursuit of

those astronomical observations, and in that context the above mentioned civilizations mirrored those of the ancient Babylonians.

The Maya observational skills of star locations merit special mention: their precision exceeded that of the early 16th century European, the time of the obliteration of that Central American culture at the hands of the Spanish conquerors.

Renaissance

With the waning of the Islamic Golden Age we have reached a pivotal point in this narrative: the dawning of the European Renaissance. This rebirth, in my view, was principally embodied by Nicolas de Cusa, a German polymath and Catholic bishop (he became a cardinal in1448), who was the first proponent of Renaissance Humanism. His works cover a wide range of subjects but in what pertains to astronomy, he affirmed that the Earth is a star like other stars, is not the centre of the universe, is not at rest, nor are its poles fixed, the celestial bodies are not strictly spherical, nor are their orbits circular, and also wrote about the possibility of the plurality of worlds. These ideas would probably have been labelled as heretical a century later but, apparently, were not considered as such in mid-15th century. My view is that the expansion of the influence of the Inquisition and the advent of the Reformation subsequently hardened the attitude of the Vatican which became thoroughly intolerant of such heterodox ideas.

The next momentous step was achieved by Nicolaus Copernicus. It was the first crucial inroad destined to displace and replace the Aristotelian geocentric universe that had reigned in various incarnations for hundreds of years. A Polish polyglot and polymath, Copernicus obtained a doctorate in canon law and was a mathematician, astronomer, physician, classics scholar, translator, governor, diplomat, and economist. A doctorate in Canon Law, or Juris Canonici Doctor (J.C.D.), is the highest degree in the study of the Catholic Church’s legal system.

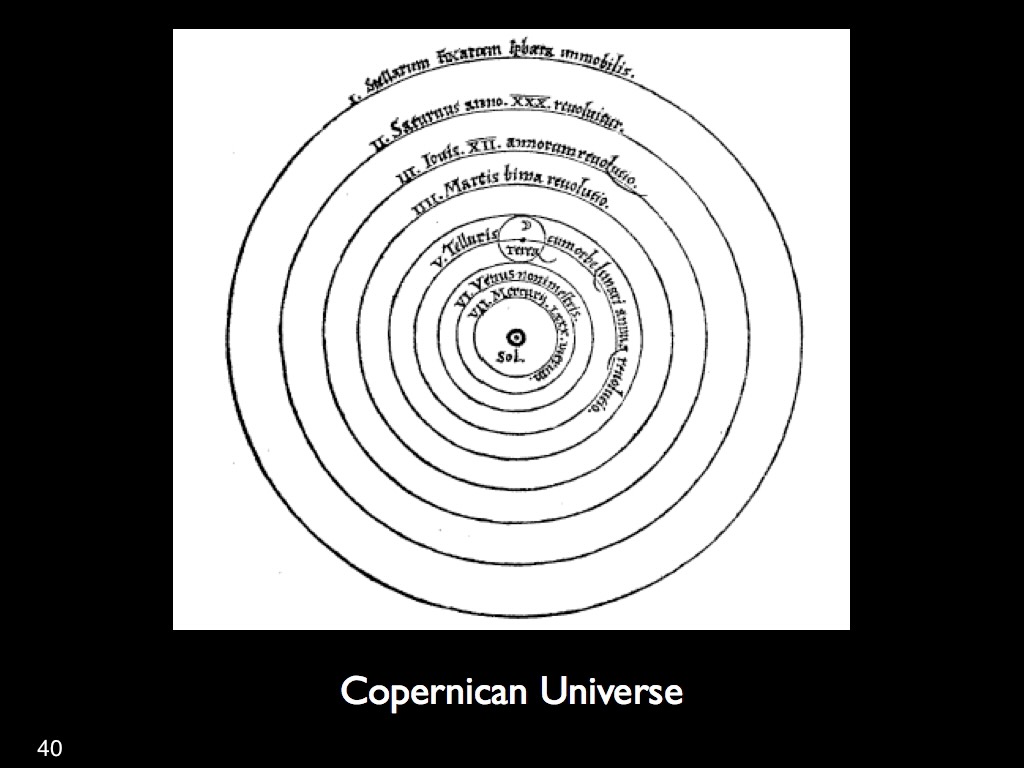

In what concerns us, Copernicus concentrated on astronomical observations after about the year 1500, at the age of 27, with an emphasis on planetary motions. He initiated his analysis of the logical contradictions in the two “official” systems of astronomy, Aristotle’s theory of homocentric spheres, and Ptolemy’s mechanism of eccentrics and epicycles, the surmounting and discarding of which would be the first step toward the creation of Copernicus’s own heliocentric doctrine of the structure of the universe. Some time before 1514, Copernicus wrote an initial outline of his heliocentric theory, known only from later transcripts, by the title commonly referred to as the Commentariolus.

It was not until just before his death in 1543 that his momentous book De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres) was published. It has been speculated that he wanted to forestall any negative and potentially dangerous Church reaction to his “deviant” theory. Interestingly, two of the most famous Protestant names of the time, Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon, rejected Copernicus’s system, although it was embraced in some Protestant realms such as Germany by Johannes Kepler and in England by Thomas Digges.

One of the subjects that Copernicus could have studied was astrology, since it was considered an important part of a medical education. Unlike most other prominent Renaissance astronomers, however, and to his credit, he appears never to have practiced nor expressed any interest in astrology. Although we must admire the originality and mathematical thoroughness evinced by Copernicus in formulating his heliocentric theory, it must be kept in mind that he persisted in maintaining two erroneous “ought to be” aspects: the circularity of all planetary orbits, and the nearby concentricity of the sphere of “fixed stars”. The latter having been already rejected 18 centuries earlier by Aristarchus who speculated that the stars are suns at an infinitely greater distance than the Sun and its planets.

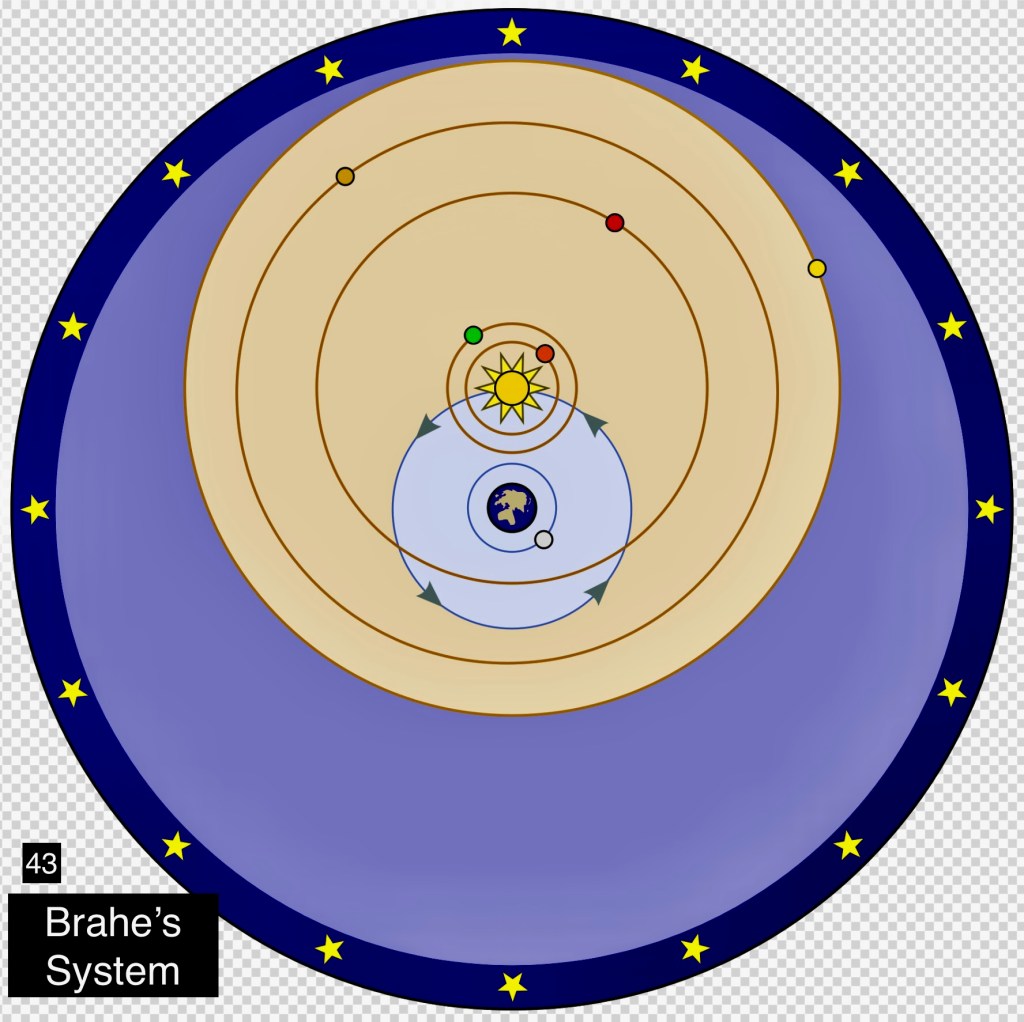

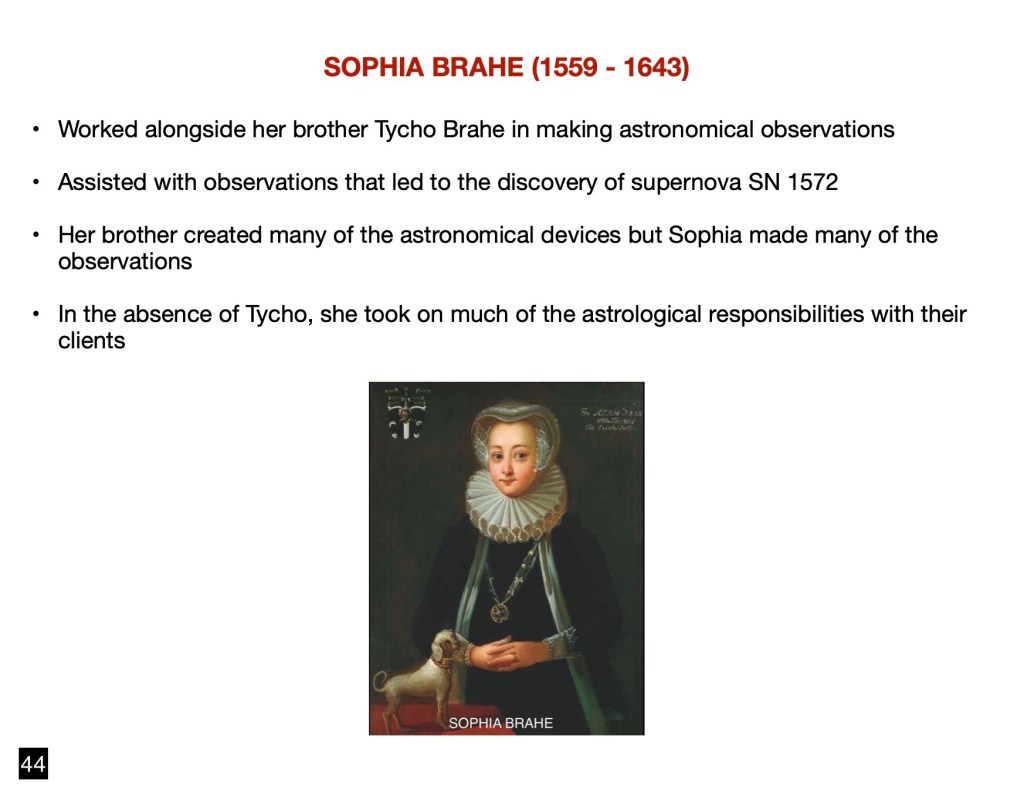

In the aftermath of the publication of Copernicus’s book, a gradual resistance to the acceptance of his heliocentric system arose. The dethroning of the Earth from its centrality was opposed by the established institutions, especially but not only by the Catholic Church. Towards the end of the 16th century a notable Danish astronomer, Tycho Brahe, expounded a new version of the solar system that attempted to solve the inconsistencies and complications of the ptolemaic system while preserving the centrality of the Earth. Brahe’s solution consisted of the planets, except the Earth, orbiting the Sun and the Sun orbiting the Earth. Tycho Brahe, however, made solid contributions to observational astronomy. He built the most advanced instruments and performed the most precise pre-telescopic positional measurements to date, providing invaluable data for the crucial subsequent advances by his student, Johannes Kepler which we will treat further on. We must acknowledge crucial contributions to Tycho Brahe’s observations by his sister Sophia Brahe leading to the discovery of supernova SN 1572. In his absence, she took on much of the astrological responsibilities with their clients. The preparation of horoscopes provided vital income to astronomers until the waning of the 17th century. We must mention at this point a tragic figure in the history of astronomy: Giordano Bruno, ordained a priest in 1572 at age 24.

Italian philosopher, poet, alchemist, astrologer, cosmological theorist, Bruno is known for his cosmological theories, which included the embrace of the Copernican model. He practiced Hermeticism and gave a mystical stance to exploring the universe. He proposed that the stars were distant suns surrounded by their own planets (now called exoplanets), and he raised the possibility that these planets might foster life of their own, a cosmological position known as cosmic pluralism. He also insisted that the universe is infinite and could have no centre. These advanced ideas and his theological views such as denial of several core Catholic doctrines, including eternal damnation, the Trinity, the deity of Christ, the virginity of Mary, transubstantiation and Bruno’s embrace of pantheism led the Inquisition to find him guilty of heresy, and he was burned at the stake in Rome’s Campo de’ Fiori in 1600.

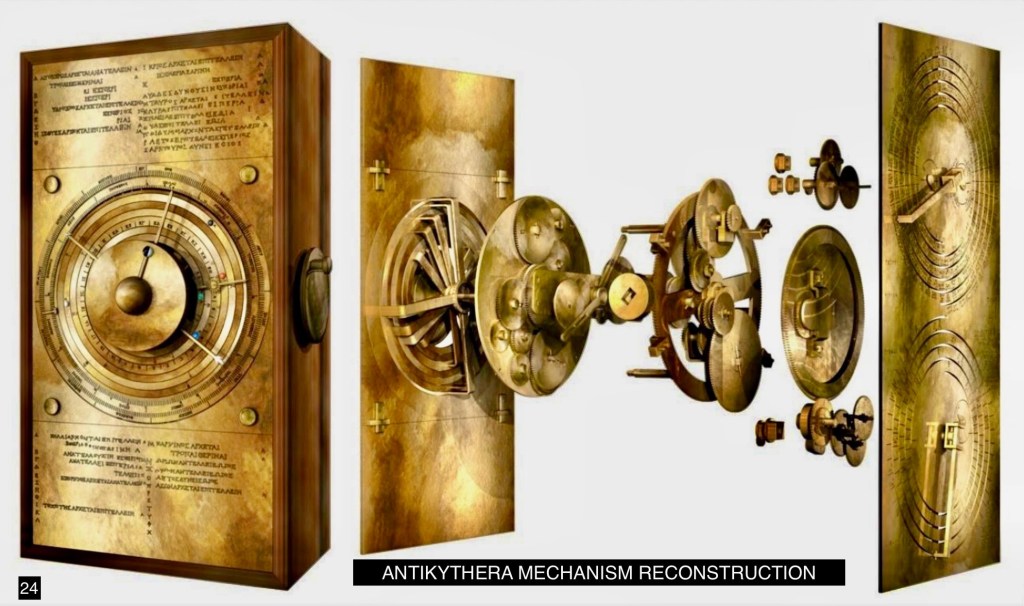

The Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment

We have now reached a decisive juncture in the advancement of astronomy: Galileo Galilei and his breakthroughs.

Galileo was born in the city of Pisa, then part of the Duchy of Florence. He has been called the father of observational astronomy, modern classical physics, the scientific method, and modern science, in general. Within this essay we will concentrate on Galileo’s astronomical achievements leaving aside his significant contributions in various fields of physics and engineering. Galileo’s involvement with Astronomy may have started with observation and discussion of Kepler’s Supernova in 1604. Since this new star displayed no detectable diurnal parallax, Galileo concluded that it was a distant star, and, therefore, disproved the Aristotelian belief in the immutability of the heavens.

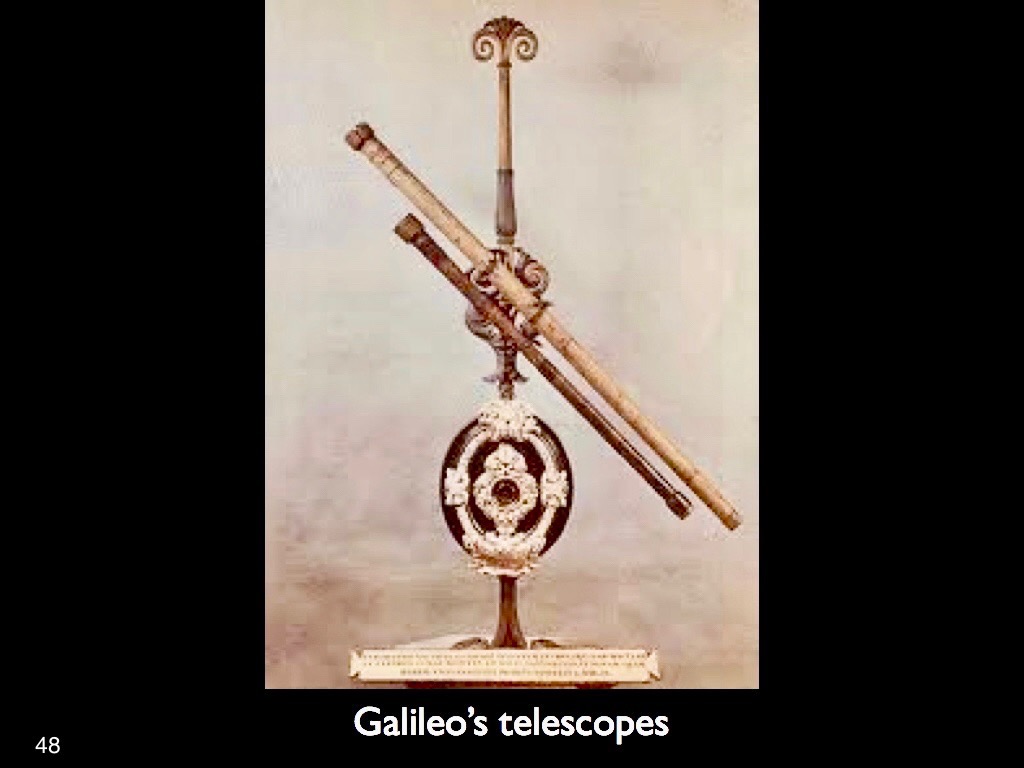

Most probably, based only on descriptions of the first practical telescope which Hans Lippershey had invented in the Netherlands in 1608, Galileo, in the following year, made a telescope with about 3× magnification and subsequently, constructed improved versions with up to about 30× magnification. He published his initial telescopic astronomical observations in March 1610 in a brief treatise entitled Sidereus Nuncius (Starry Messenger). On November 1609, Galileo made his first observations of the Moon and discerned for the first time the presence of mountains and craters on our satellite. Between January 7 and 13 he observed the planet Jupiter and discovered its four largest moons which, subsequently, have been named the Galilean moons.

Galileo’s observations of the moons of Jupiter caused widespread controversy since a planet with smaller planets orbiting it did not conform to the principles of Aristotelian cosmology, which held that all heavenly bodies should only circle the Earth. This provided further support to the Copernican heliocentric system.

As cited in Wikipedia, “Galileo saw a practical use for his discovery. Determining the east–west position of ships at sea required their clocks to be synchronized with clocks at the prime meridian. Solving this longitude problem had great importance to safe navigation and large prizes were established by Spain and later Holland for its solution. Since eclipses of Jupiter’s moons he discovered were relatively frequent and their times could be predicted with great accuracy, they could be used to set shipboard clocks and Galileo applied for the prizes. Observing the moons from a ship proved too difficult, but the method was used for land surveys, including the remapping of France”. As we will see, long term observation of the eclipses of the satellites of Jupiter led to an unexpected discovery by Ole Rømer, later in the 17th century: the finite velocity of light and its magnitude,.

Starting in September 1610, Galileo observed the planet Venus and found that it went through phases similar to those of the Moon. This further confirmed the heliocentric model of the Solar System of Nicolaus Copernicus.

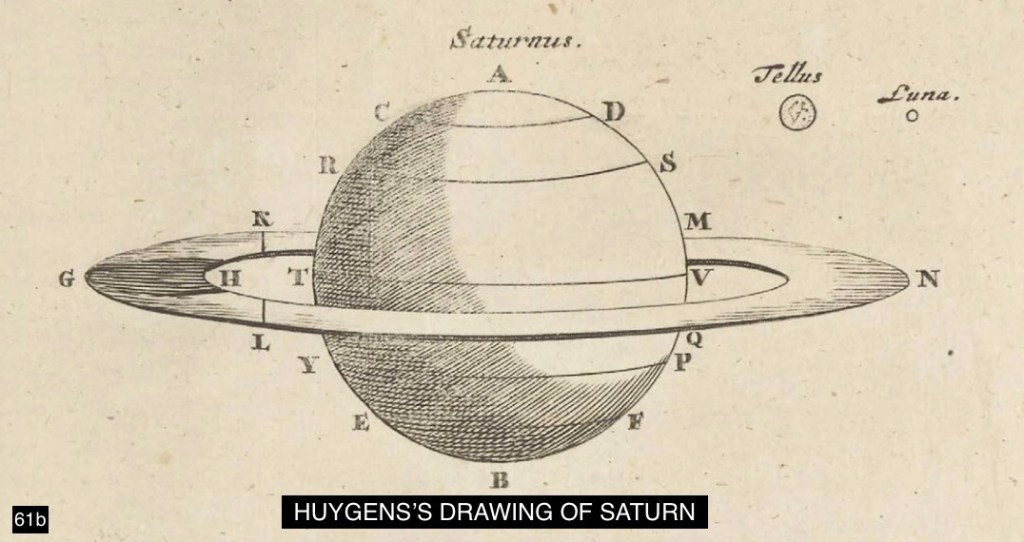

Also, in 1610, Galileo observed the planet Saturn, and at first mistook its rings for planets, thinking it was a three-bodied system. When he observed the planet later, Saturn’s rings were directly oriented to Earth, causing him to think that two of the bodies had disappeared. The rings reappeared when he observed the planet in 1616, further confusing him. He also thought that the rings were appendices of the planet and depicted them as handles.

He also observed the Milky Way and, correctly, identified it for the first time as an assembly of numerous stars. In addition, Galileo observed solar spots, blemishes that contradicted the perfection of the cosmos. Galileo’s embracing of heliocentrism, however, was to put him eventually in the crosshairs of the Inquisition. He had been charged by Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, who had become Pope Urban VIII in 1623, to write a book comparing the two systems, the geocentric and the heliocentric. Barberini was a friend and admirer of Galileo. Galileo’s resulting book, Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, was published in 1632, with formal authorization from the Inquisition and papal permission. This authorization, however, was given on the assumption that Galileo would not treat preferentially either of the two systems. Whether intentionally or not, Galileo appeared to side with heliocentrism. He was commanded to appear before an Inquisitor and made to recant any approval of Copernicanism under threat of torture after which he was condemned to imprisonment which was commuted to permanent house arrest. His Dialogue book, was banned by the Church. It is worth noting that on 31 October 1992, Pope John Paul II finally, after more than three centuries, acknowledged that the Inquisition had erred in condemning Galileo for asserting that the Earth revolves around the Sun. John Paul said that the theologians who condemned Galileo “did not recognize the formal distinction between the Bible and its interpretation”. The pioneering use of the telescope by Galileo thereafter transformed astronomy and opened veritable observational floodgates that are continued to this date.

I had mentioned the name Johannes Kepler in his role of assistant to Tycho Brahe, the great Danish astronomer, during the waning years of the 16th century. We will now consider the remarkable contributions to astronomy by Kepler which, in combination with those of Galileo, were to set an entirely new course for that science. Kepler was an an avowed heliocentrist, in protestant Germany, thus shielded from Roman Catholic persecution. He had been in communication with Galileo and shared ideas with the Italian astronomer. Johannes Kepler was a German astronomer, mathematician, natural philosopher, astrologer, key figure in the 17th century Scientific Revolution. Kepler Kepler incorporated religious arguments and reasoning into his work, motivated by the conviction and belief that God had created the world according to an intelligible plan that is accessible through the natural light of reason. For many years he attempted to find a geometric foundation to the orbits of the planets, based on nested

3-dimensional polyhedra based on the concept that the Creator structured the solar system accordingly. This relying on divine cosmic architecture was Kepler’s adherence to medieval logic. He eventually abandoned that belief in a godly design after many years of futile efforts.

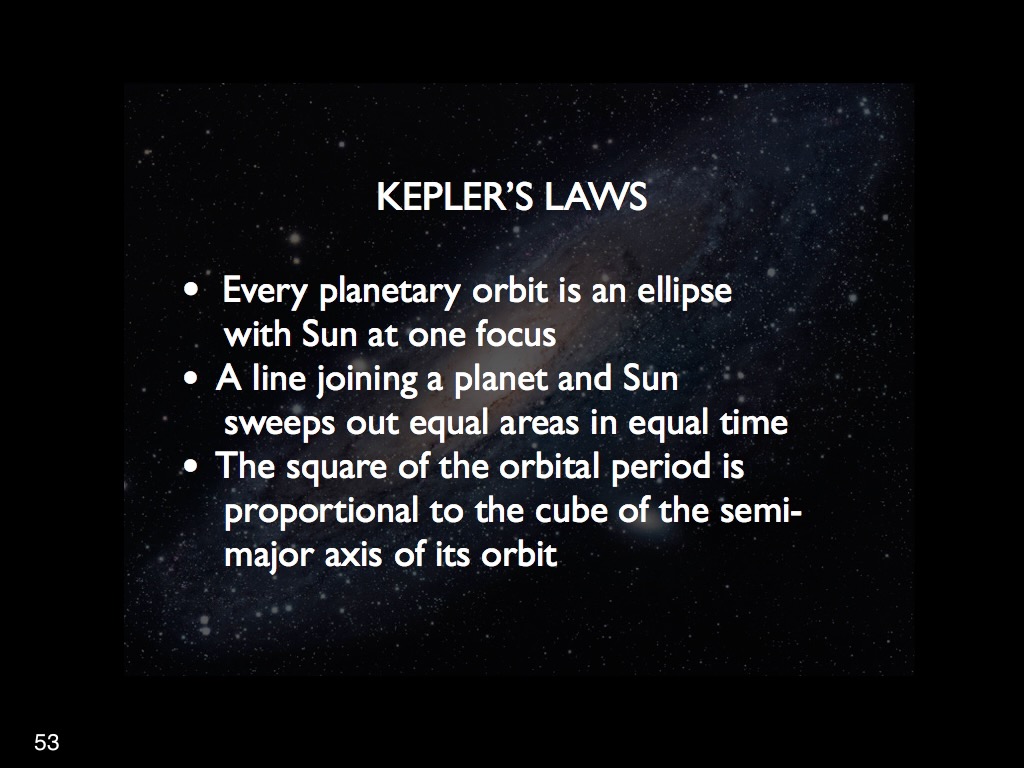

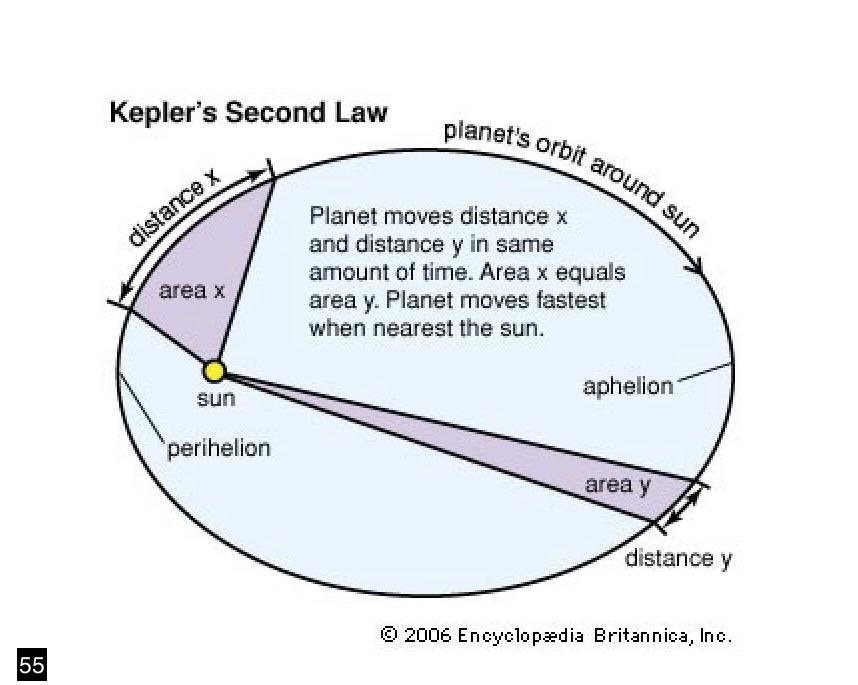

Kepler observed the SN 1604 supernova and concluded that it was located in the sphere of fixed stars and not within the solar system because of the lack of observed parallax, thus undermining the Aristotelian doctrine of the immutability of the cosmos. Kepler is best known for his three laws of planetary motion which provided the foundation for Newton’s Theory of Universal Gravitation. These three laws were as follows: The orbit of a planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the two foci. A line segment joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time. The square of a planet’s orbital period is proportional to the cube of the length of the semi-major axis of its orbit.

The elliptical orbits of planets were indicated by calculations of the orbit of Mars. From this, Kepler inferred that the other planets of the Solar System, also have elliptical orbits. The second law establishes that when a planet is closer to the Sun, it travels faster. The third law expresses that the farther a planet is from the Sun, the longer its orbital period. As indicated in Wikipedia: “Galileo sought the opinion of Kepler, in part to bolster the credibility of his observations. Kepler responded enthusiastically with a short published reply, Dissertatio cum Nuncio Sidereo [Conversation with the Starry Messenger]. He endorsed Galileo’s observations and offered a range of speculations about the meaning and implications of Galileo’s discoveries and telescopic methods, for astronomy and optics as well as cosmology and astrology. Later that year, Kepler published his own telescopic observations of Jupiter’s moons in Narratio de Jovis Satellitibus, providing further support of Galileo. To Kepler’s disappointment, however, Galileo never published his reactions (if any) to Astronomia Nova”. Kepler also developed an improved telescope—now known as the astronomical or Keplerian telescope—in which two convex lenses can produce a higher magnification than Galileo’s combination of convex and concave lenses. This became the design for future refracting telescopes. For those interested in details about Kepler’s convoluted life and brilliant achievements I advise reading the book to which I alluded previously: The Sleepwalkers by Arthur Koestler. It also provides carefully elaborated insights about Copernicus and Galileo and the latter’s interplay with Kepler.

One of the thematic objectives of this historical essay is to acknowledge the crucial contributions to the advancement of astronomy, largely unsung, of women who, most frequently, worked in the shadow of famous astronomer husbands and brothers.

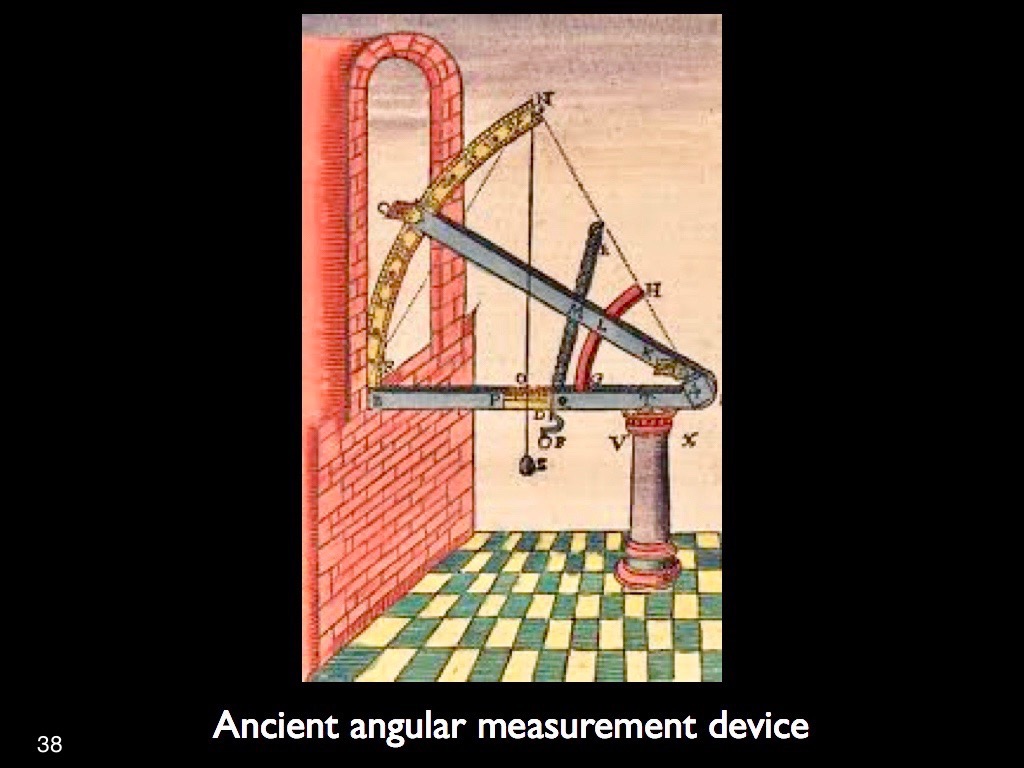

I had started on that quest with Sophia Brahe and the next one I will address is Elizabeth Hevelius, the spouse of Johannes Hevelius, a Polish astronomer of international repute who lived in the second half of the 17th century. Elizabeth assisted her husband in performing observations through several large telescopes that he owned. She was self taught in Latin and was thus able to correspond with fellow astronomers. Following Johannes’s death she undertook the completion and publication, in 1690, of Elements of Astronomy that included a catalog of 1,564 stars. Elizabeth’s contributions were both quantitative and qualitative with a meticulous and systematic approach to astronomical research.

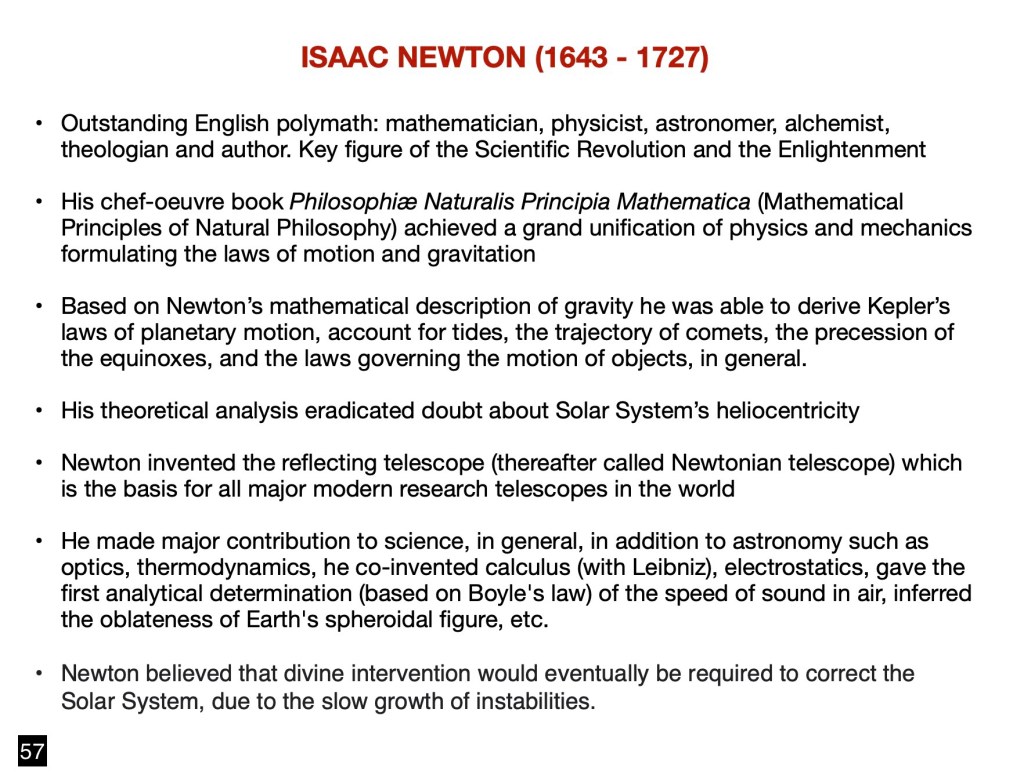

We have now reached the zenith of the Scientific Revolution in the person of Isaac Newton and his disciples, straddling the second half of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th, leading into the subsequent Enlightenment.

Newton occupies a particularly exalted position in that his main contribution to astronomy provided a springboard for much of its progress until the present. The calculations underlying most of the orbital space explorations, since the second half of the 20th century, are based on the equations developed by that remarkable English polymath. He remains, in the company of Albert Einstein, a true genius of the physical sciences.

We will restrict here the treatment of Newton’s achievements to what pertains to astronomy, although we must recognize his remarkable contributions that far transcended that discipline.

We must also acknowledge Newton’s unproductive and wasteful excursions into mysticism and alchemy which occupied much of his attention during his mature years. To some extent he could not divorce himself from a medieval inheritance, similarly to his predecessor, Johannes Kepler.

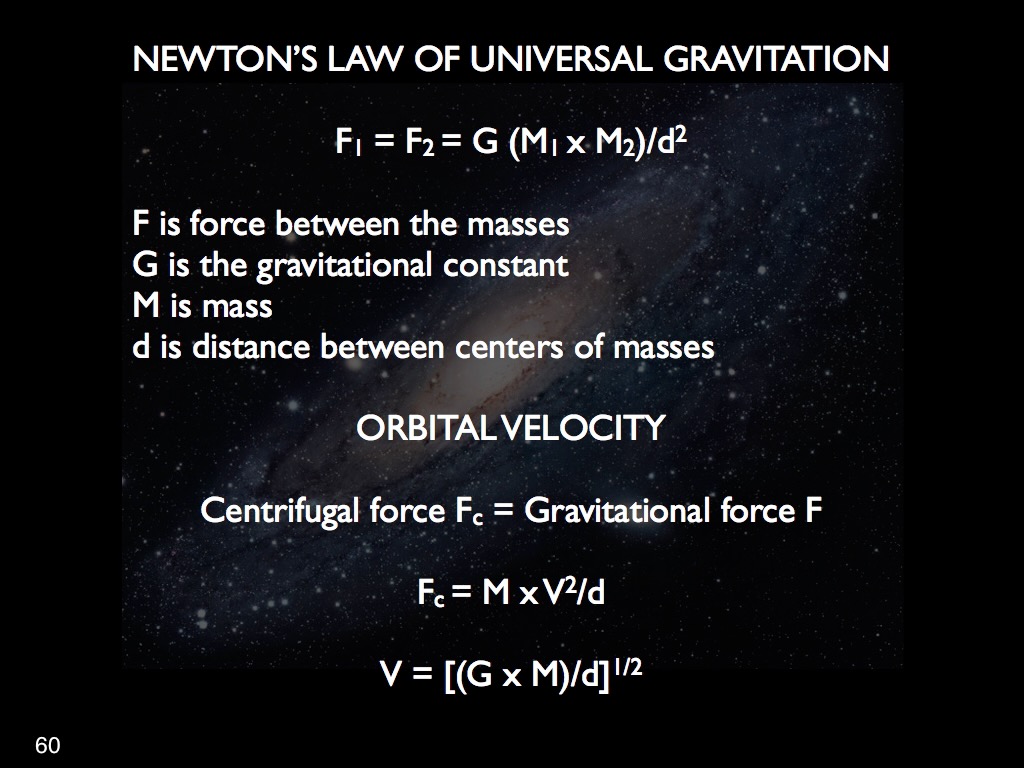

Newton’s chef-d’oeuvre Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), first published in 1687, achieved the first great unification in physics and the established classical mechanics. In the words of Stephen Hawking, the notable British astrophysicist: “Newton fused the scientific contributions of Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler and others into a dynamic new symphony. Principia, the first book on theoretical physics, is roundly regarded as the most important work in the history of science and the scientific foundation of the modern worldview”.

As mentioned in his Wikipedia entry: “In the Principia, Newton formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation that formed the dominant scientific viewpoint for centuries until it was superseded by the theory of relativity. He used his mathematical description of gravity to derive Kepler’s laws of planetary motion, account for tides, the trajectories of comets, the precession of the equinoxes and other phenomena, eradicating doubt about the Solar System’s heliocentricity. Newton solved the two-body problem, and introduced the three-body problem. He demonstrated that the motion of objects on Earth and celestial bodies could be accounted for by the same principles. Newton’s inference that the Earth is an oblate spheroid was later confirmed”. This latter statement will be elaborated on subsequently.

Reverting to his theological penchant, however, Newton believed that divine intervention would occasionally be required to correct any disorderly drifts of the planets of the Solar System, due to the slow growth of instabilities which he recognized as inevitable.

Among his insightful conclusions, Newton expounded his heliocentric view of the Solar System in a somewhat modern way as he recognized the actual centre of gravity of the Solar System. For Newton, it was not precisely the centre of the Sun or any other body that could be considered at rest, but rather “the common centre of gravity of the Earth, the Sun and all the Planets is to be esteem’d the Centre of the World”, and this centre of gravity “either is at rest or moves uniformly forward in a right line”. (Newton chose the “at rest” alternative based on the prevailing belief that the Solar System itself did not move through space. This latter view was to be amended in the early 20th century when it was determined that the Solar System rotates around the center of gravity of the Milky Way galaxy which, in turn is in motion.

Another crucial contribution to astronomy was that of the reflecting telescope invented by Isaac Newton as an alternative to the refracting telescope which, at that time, was a design that suffered from severe chromatic aberration. Although reflecting telescopes produce other types of optical aberrations, it is a design that allows for very large diameter objectives, presently well beyond possible dimensions of refracting telescopes which are based on the use of lenses. Almost all of the major telescopes used in contemporary astronomy research are of the reflector type, i.e., based on a variety of mirror configurations.

Consistent with our mission to give due credit to women astronomers, we need to introduce at this post-Newton juncture Émilie du Châtelet a towering figure of the early Enlightenment.

Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, Marquise du Châtelet was a French physicist, mathematician and philosopher. Her most important contribution to astronomy was her translation into French, with an extensive commentary, of Isaac Newton’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. The text, published posthumously in 1756, is still considered the standard French translation to this day.

To undertake a formidable project such as this, du Châtelet prepared to translate the Principia by broadening her studies in analytic geometry, mastering calculus, and reading important works in experimental physics. It was her rigorous preparation that allowed her to add a lot more accurate information to her commentary, both from herself and other scientists she studied or worked with. She was one of only 20 or so people in the 1700s who could understand such advanced math and apply the knowledge to other works. Du Châtelet made very important corrections in her translation that helped support Newton’s theories about the universe.

Du Châtelet died in childbirth at the early age of 42.

Nearly contemporaneous with Newton we must cite a notable Dutch astronomer, Christiaan Huygens, who was called upon to join the French Academy of Sciences at invitation of King Luis XIV.

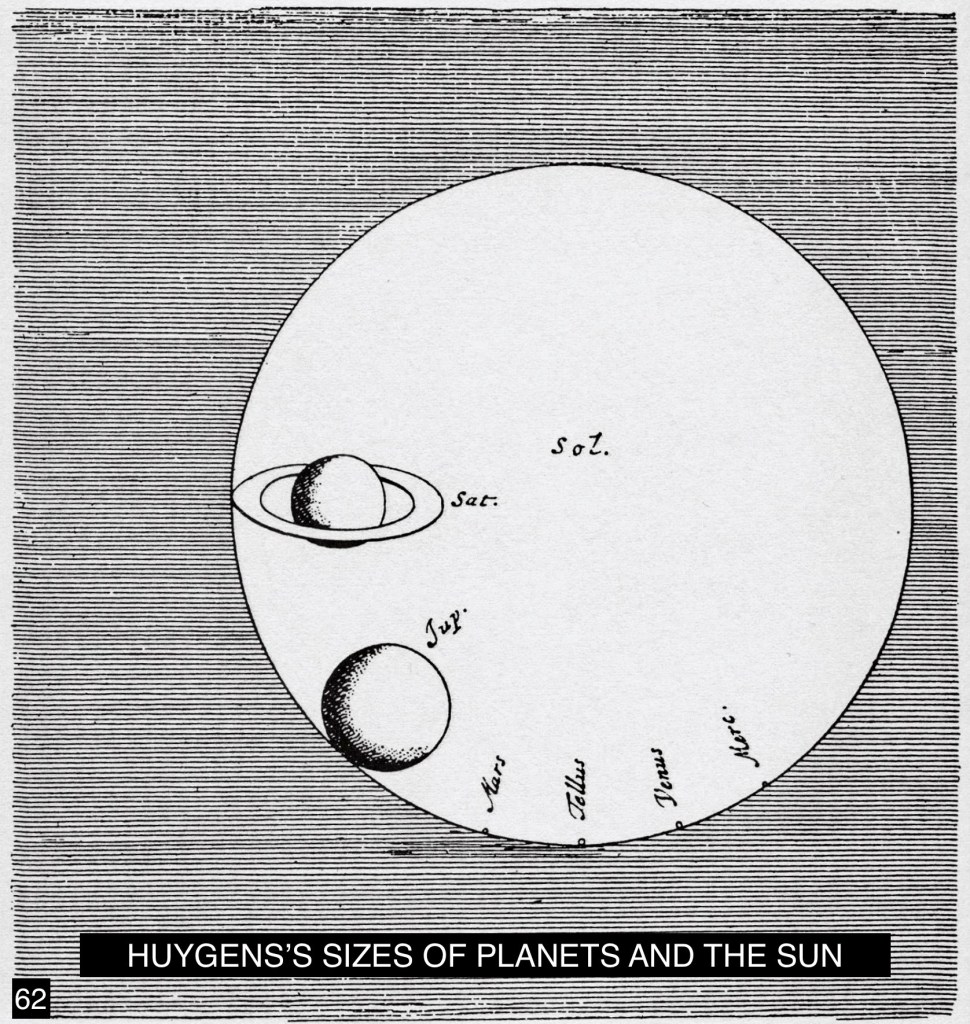

Huygens was a mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor who is regarded as a key figure in the Scientific Revolution. In 1655, Huygens discovered the first of Saturn’s moons, Titan, and observed and sketched the Orion Nebula using a refracting telescope with a 43x magnification of his own design. Huygens discovered several double stars. He was also the first to propose that the appearance of Saturn, which had baffled astronomers, was due to a thin, flat ring, nowhere touching the planet. More than three years later, in 1659, Huygens published his theory and findings in Systema Saturnium. It is considered the most important work on telescopic astronomy since Galileo. Huygens provided measurements for the relative distances of the planets from the Sun, introduced the concept of the micrometer, and showed a method to measure angular diameters of planets, which finally allowed the telescope to be used as an instrument to measure — rather than just sighting — astronomical objects. Huygens’s achievements were highly significant and were only eclipsed by those of Isaac Newton’s.

Resuming my acknowledgment of notable women astronomers, we must mention Marie-Jeanne de Lalande, daughter of well known astronomer Jérôme Lalande. She lectured in astronomy in Paris and during the French Revolution, the chief of the Paris Observatory, Dominique, comte de Cassini, asked Marie-Jeanne for help. She taught Cassini’s son and helped him make his first observations of at the Collège de France.

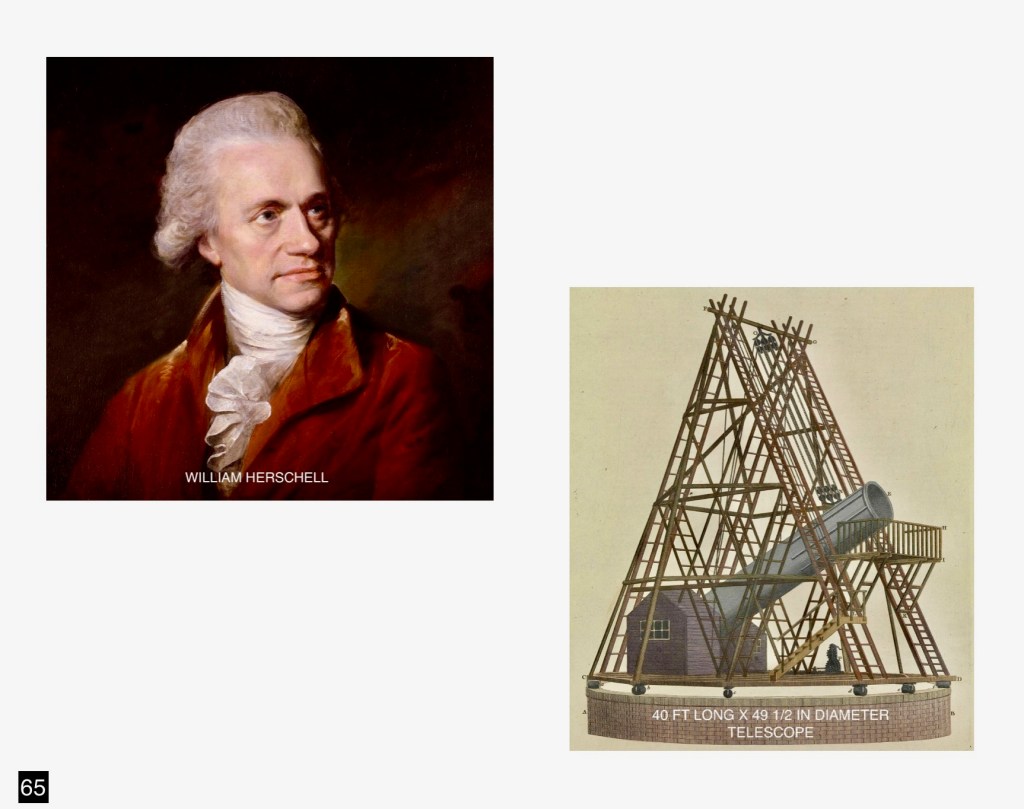

She calculated the Tables horaires de marine, which was published in Jérôme Lalande’s Abrégé de navigation historique théorique et pratique avec tables horaires (1793). These calculations earned Jérôme Lalande one of the medals of the Lycée des Arts for distinguished scholars and artists. He dedicated the award to Marie-Jeanne de Lalande. In 1785, in the preface to Astronomie des dames by Jérôme Lalande, he cites Marie-Jeanne de Lalande as one of the greatest female astronomers In 1799, she established a catalog of 10,000 stars.She also collaborated on the writing of L’Histoire céleste française written by Lalande and published in 1801. The work indicated the position of nearly 50,000 stars. Frederick William Herschel was a German-British astronomer as well as composer. He frequently collaborated with his younger sister and fellow astronomer Caroline Herschel, to whom I will refer further on. Born in the Electorate of Hanover, William Herschel followed his father into the military band of Hanover, before immigrating to Britain in 1757 at the age of nineteen.

The high resolving power of the telescopes Herschel built revealed that many objects called nebulae were actually clusters of stars. On 13 March 1781 he made note of a new object in the constellation of Gemini. This would, after several weeks of verification and consultation with other astronomers, be confirmed to be a new planet, eventually given the name of Uranus. This was the first planet to be discovered since antiquity and, as a result, Herschel became famous overnight.

He is reported to have cast, ground, and polished more than four hundred mirrors for reflecting telescopes of his design (called Herschelian telescopes), varying in size from 6 to 48 inches in diameter. Herschel and his assistants built and sold at least sixty complete telescopes of various sizes. Commissions for the making and selling of mirrors and telescopes provided Herschel with an additional source of income. The King of Spain reportedly paid £3,150 for one of his telescopes.

The largest and most famous of Herschel’s telescopes was a reflecting telescope with a 491⁄2-inch-diameter (1.26 m) primary mirror and a 40-foot (12 m) focal length. This 40-foot telescope was, at that time, the largest scientific instrument that had been built. It was hailed as a triumph of “human perseverance and zeal for the sublimest science”. In 1789, shortly after this instrument became operational, Herschel discovered a new moon of Saturn: Mimas, only 250 miles (400 km) in diameter.

Discovery of a second moon (Enceladus) followed, within the first month of observation.

Later on Herschel discovered two moons of Uranus, Titania and Oberon. He did not give these moons their names; they were named by his son John in 1847 and 1852, respectively, after his death. Herschel measured the axial tilt of Mars and discovered that the Martian ice caps, first observed by Giovanni Domenico Cassini (1666) and Christiaan Huygens (1672), changed size with that planet’s seasons. It has been suggested that Herschel discovered the faint rings around Uranus.

One of the unknowns with which natural philosophers — now called scientists — were wrestling with is whether light moves with a finite velocity or whether it is transmitted instantaneous, with infinity speed. Galileo had attempted to measure that speed but was unable to do so with the primitive means at his disposal, i.e., blocking and unblocking candles separated by a mile, or so. Success in that endeavor had to wait for over a half a century and as a result of an unforeseen observation.

Galileo himself, ever the practical scientist, had suggested that the relatively rapid and extremely repeatable motion of the four satellites of Jupiter that he had discovered could be used as a reliable clock required to determine geographical longitude in navigation. In the 1670s, astronomers in France used observations of Jupiter’s moons to conduct a groundbreaking survey that led to the first accurate map of the country.

As mentioned previously when discussing Galileo’s idea, careful cataloguing of the Jupiter moons positions was hoped to provide reliable determinations of longitude. This objective, however, proved to be unreliable over the long term. Unexpected gradual deviations of the predicted positions of these moons were observed. These discrepancies led to a groundbreaking discovery by a young Danish astronomer, Ole Roemer. He correctly had the insight that those apparent orbital discrepancies were caused by the finite speed of light which caused the apparent positions of Jupiter’s moons to shift as the distance between the Earth and Jupiter varied. Roemer made his discovery regarding the speed of light while working at the Royal Observatory in Paris observing Jupiter’s moon Io between 1671 and 1677. He estimated that on that basis light travels at 220,000 kilometers per second, compared to today’s accepted value of just under 300,000 kilometers per second, still a remarkable achievement.

This discovery of the finite speed of light is one example of the crucial role of astronomy in the advancement of the physical sciences.

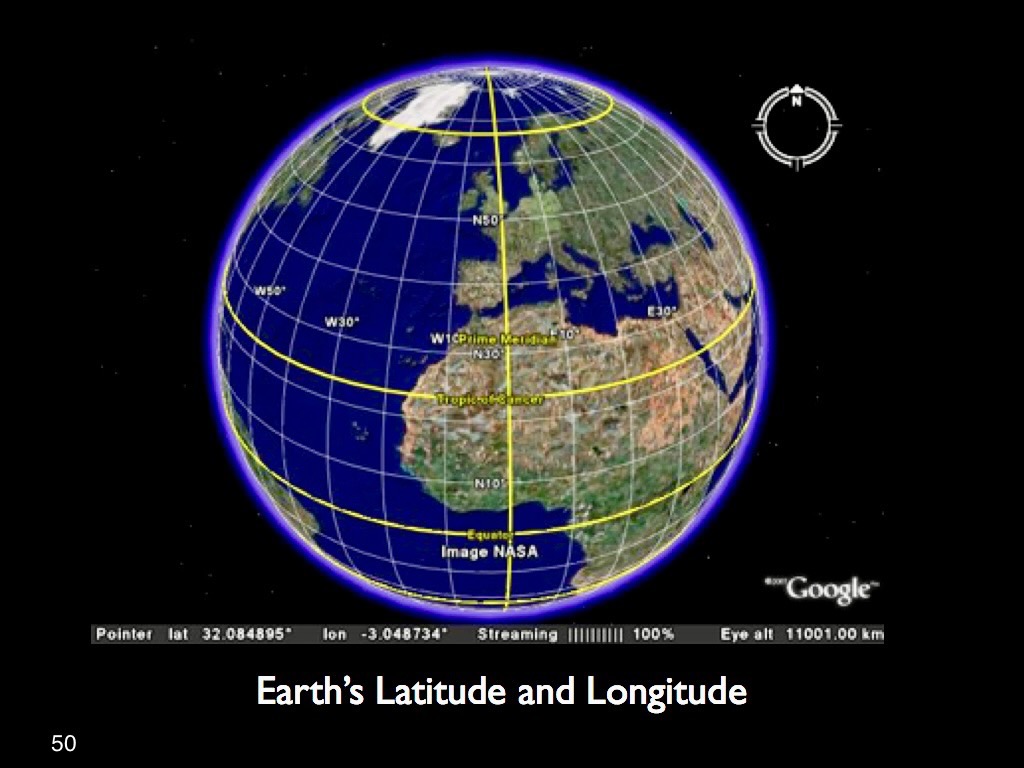

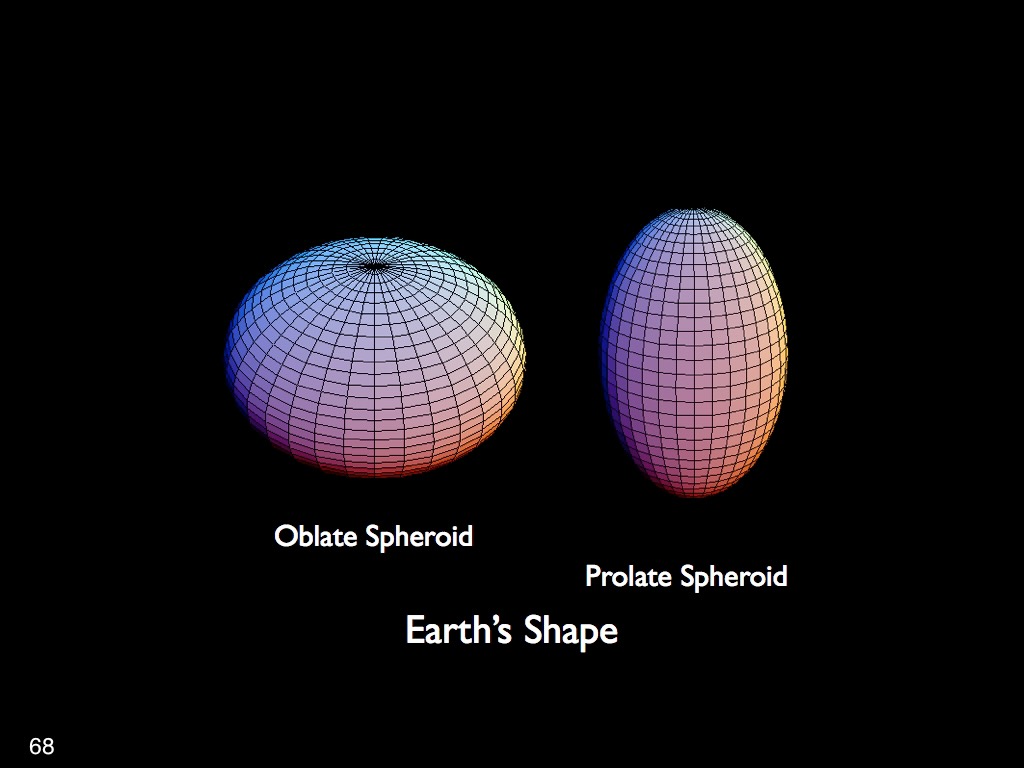

Another question that preoccupied physicists and astronomers at the end of the 17th century was the true shape of the Earth. It had been suspected that it was not a perfect sphere. but if not, then is it an oblate spheroid — bulging at the equator and flatten at the poles, which Newton had predicted, or a prolate spheroid — elongated at the poles and flattened at the equator, as assumed by the astronomer Domenico Cassini? This unknown had practical implications: navigation depended on the precise determination of geographical location which was ascertained by measuring angular coordinates from which distances could be determined. The relationship between angular coordinates and distance, in turn depended on the curvature of the Earth at the location of a ship. Henceforth the need to know that curvature at the location of the vessel.

Consequently, the French Academy of Sciences decided to resolve this quandary by sponsoring two expeditions to measure the curvature of the Earth, one of them as far north as possible, i.e., as near to the north pole as early 18th century travel conditions allowed, and the other to a location near the equator. The northern expedition went to Lapland in Sweden and completed their survey in a few months without major obstacles. The mission to the equator, however, proved to be an altogether different matter. It took about seven years of arduous efforts under difficult conditions. Three notable French scientists with their helpers performed meticulous observations in the 1730s in what is now the nation of Ecuador, principally in the Andean highlands. That territory was at that time part of the Spanish colonial Viceroyalty of Nueva Granada, a large region of northwest South America. The story of their struggles has become the subject of several books. Finally, the members of the expedition gradually made it back to France and the results of the two missions were compared clearly confirming Newton’s prediction: the Earth is an oblate spheroid, bulging around the equator as a result of centrifugal deformation caused by Earth’s diurnal rotation.

Next in our review of major players in the field of astronomy is a towering figure: Pierre-Simon Laplace. I’m going to take the liberty of citing the introduction to his Wikipedia entry:

Laplace was “a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summarized and extended the work of his predecessors in his five-volume Mécanique céleste (Celestial Mechanics) (1799–1825). This work translated the geometric study of classical mechanics to one based on calculus, opening up a broader range of problems. Laplace also popularized and further confirmed Sir Isaac Newton’s work. In statistics, the Bayesian interpretation of probability was developed mainly by Laplace.

Laplace formulated Laplace’s equation, and pioneered the Laplace transform which appears in many branches of mathematical physics, a field that he took a leading role in forming. The Laplacian differential operator, widely used in mathematics, is also named after him. He restated and developed the nebular hypothesis of the origin of the Solar System and was one of the first scientists to suggest an idea similar to that of a black hole, with Stephen Hawking stating that “Laplace essentially predicted the existence of black holes”. He originated Laplace’s demon, which is a hypothetical all-predicting intellect. He also refined Newton’s calculation of the speed of sound to derive a more accurate measurement.

Laplace is regarded as one of the greatest scientists of all time. Sometimes referred to as the French Newton or Newton of France, he has been described as possessing a phenomenal natural mathematical faculty superior to that of almost all of his contemporaries. He was Napoleon’s examiner when Napoleon graduated from the École Militaire in Paris in 1785. Laplace became a count of the Empire in 1806 and was named a marquis in 1817, after the Bourbon Restoration.

As to his remarkable foresight on black holes: He suggested that gravity could influence light and that there could be massive stars whose gravity is so great that not even light could escape from their surface. However, this insight was so far ahead of its time that it played no role in the history of scientific development.

Laplace’s accomplishments in a wide range of scientific and mathematical field are well beyond the scope of this writing. His chef d’oeuvres in astronomy are two books: Exposition du système du monde and Mécanique céleste. Laplace developed the nebular hypothesis of the formation of the Solar System. This hypothesis remains the most widely presently accepted model in the study of the origin of planetary systems. According to Laplace’s description of the hypothesis, the Solar System evolved from a globular mass of incandescent gas rotating around an axis through its centre of mass. As it cooled, this mass contracted, and successive rings broke off from its outer edge. These rings in their turn cooled, and finally condensed into the planets.

At this juncture I will take the liberty to digress from the chronological sequence in this historical progression of astronomy, and mention — somewhat derisively — a pursuit that in Antiquity propelled the study of the cosmos and later became a parallel endeavor to astronomy, namely astrology. During the Renaissance and, in Europe, until about the end of the 17th century, astrology played an important role in the observation of the heavens and provided vital income to the astronomers who practiced it, some of which questioned its scientific validity. Outside of Europe, however, astrology has not followed the demise of other, so called, occult sciences such as alchemy, and it may even have had a revival such as in the U.S. perhaps propelled by New Age fads. Even more surprising, to me at least, has been the pervasive persistence of astrological beliefs in countries such as India and China. This fact was made blindingly obvious to me when I traveled through India with my spouse in 2016. In at least one of the luxurious hotels we stayed at there was an astrology desk provided for the consultation of the guests. Equally surprising to me was when our guide took us on a visit to what was touted as a historical “astronomical observatory” in the city of Jaipur, the capital of the state of Rajasthan in northwest India. To my shock and astonishment the sprawling “observatory” had no telescope whatsoever although it had been founded in 1734 when such indispensable instruments were considered essential in the European realm. This complex, is described as follows in its Wikipedia entry: “The Jantar Mantar is a collection of 19 astronomical instruments… It features the world’s largest stone sundial, and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site… The instruments allow the observation of astronomical positions with the naked eye. The observatory is an example of the Ptolemaic positional astronomy which was shared by many civilizations”. This description obscures the fact that this “observatory” was used principally for astrological purposes since it could not perform as an installation for meaningful 18th century astronomy. It was, as Wikipedia states, about a millennia and a half (Ptolemaic astronomy) behind the times.

To conclude, I must reiterate and emphasize that astrology is merely a pseudoscience without any grounding in reality and should be relegated to the heap of worthless superstitions to which it belongs.

One the important objectives of astronomy starting in the 1600s was to make an accurate determination of the mean distance between the Earth and the Sun — what is now known as the “astronomical unit” or AU — as well as the distances between the Sun and the other planets of the Solar System. In 1663, the Scottish mathematician James Gregory had suggested in his Optica Promota that observations of a transit of Mercury, at widely spaced points on the surface of the Earth, could be used to calculate the solar parallax, and hence the astronomical unit by means of triangulation. In a paper published in 1691, and a more refined one in 1716, the British astronomer Edmund Halley proposed that more accurate calculations could be made using measurements of a transit of Venus.

Such transits are observed when a planet, such as Venus, passes in front of the Sun, thus becoming visible as a dark spot on the face of the Sun. If that passage is observed simultaneously from two distant locations on Earth, the difference between the timing of those observations can be used for parallax determinations and, hence the distance to Venus and the Sun. Once such distances are obtained, applying Kepler’s third law it is possible to calculate distances to all the planets of the Solar System. Such observations of Venus transits where then performed with increasing accuracy during the 1700s. It is worth mentioning that the transit method is presently the most frequently used method to detect the presence and size of exoplanets.

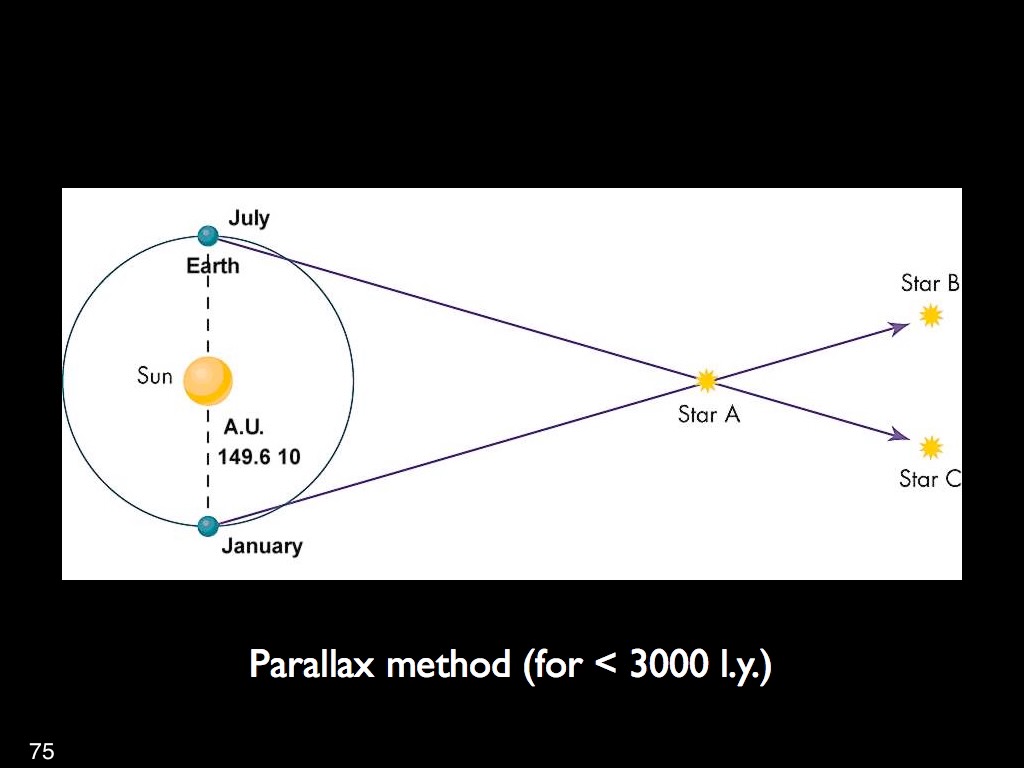

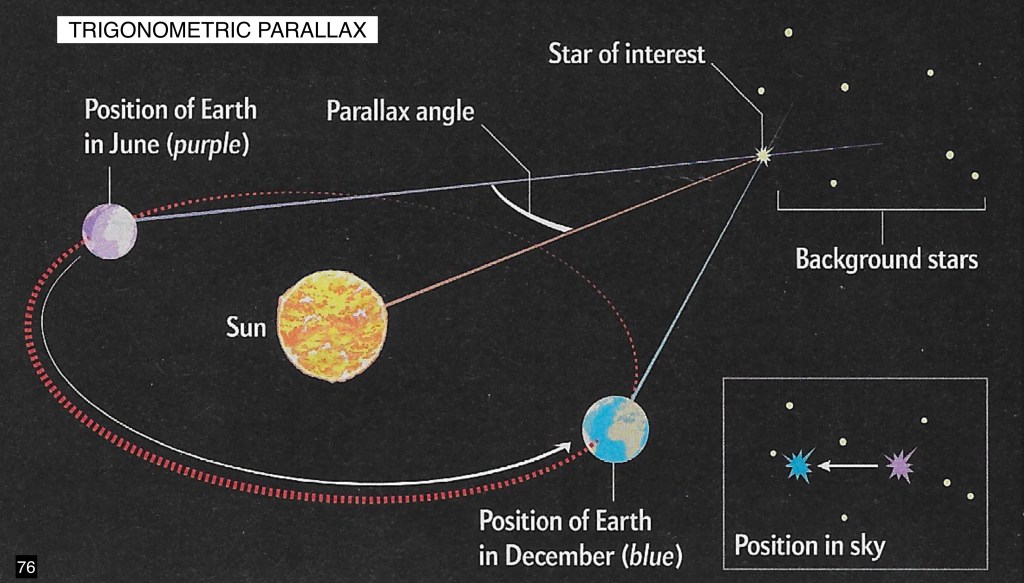

Reference has been made above to the term parallax. Again, here is the relevant Wikipedia definition: “In astronomy, parallax is the apparent shift in position of a nearby celestial object relative to distant background objects which is caused by a change in the observer’s point of view. This effect is most commonly used to measure the distance to nearby stars from two different positions in Earth’s orbital cycle, usually six months apart. By measuring the parallax angle, the measure of change in a star’s position from one point of measurement to another, astronomers can use trigonometry to calculate how far away the star is.

The concept hinges on the geometry of a triangle formed between the Earth at two different points in its orbit at one end and a star at the other. The parallax angle is half the angle formed at the star between those two lines of sight. The closer the star is to the observer, the larger the angle would be.

At present, “parallax is a foundational method in the cosmic distance ladder, a series of techniques astronomers use to measure distances in the universe… Parallax remains the most direct and reliable method for measuring stellar distances, forming the basis for calibrating more indirect methods to measure distances to galaxies and beyond”.

It is worth restating that the method of parallax was invented and applied two millennia earlier by the Hellenistic astronomers in order to measure astronomical distances, as mentioned at the beginning of this essay.

The Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

Newtonian physics and astronomy complemented by the crucial contributions of luminaries such as Huygens and Laplace, bore fruit in the singular achievement of Urbain Jean-Joseph Le Verrier, French astronomer (1811 – 1877) which was his prediction of the existence of the then unknown planet Neptune, using only mathematics and astronomical observations of the known planet Uranus. Encouraged by François Arago, Director of the Paris Observatory, Le Verrier was engaged for months in complex calculations to explain small but systematic discrepancies between Uranus’s observed orbit and those calculated from the laws of gravity of Newton. Le Verrier announced his final predicted position for Uranus’s unseen perturbing planet on 18 September 1846 in a letter to Johann Galle of the Berlin Observatory, and the planet was found with the Berlin Fraunhofer refractor the same evening the letter had arrived, 23 September 1846, by Galle, within 1° of the predicted location between the constellations Capricorn and Aquarius.

We have now entered the fertile field of the major astronomical achievements and discoveries of the 19th century of which we will mention only the most salient.

To set the stage, I would like to cite a negative statement by a rather famous French philosopher, Auguste Comte, founder of positivism. He is well known for writing in 1843 in his book The Positive Philosophy that people would never learn the chemical composition of the stars. Joseph von Fraunhofer in 1814, however, had discovered, through spectroscopy which he invented, that the light of the Sun contained dark lines which were later shown to be mostly atomic absorption lines characteristic of specific elements, as explained by Kirchhoff and Bunsen in 1859. These observations provided the means to determine the atomic composition of stars. Thus, beware of philosophers making scientific predictions.

Spectroscopy was to become one of the most powerful tools of astronomy, eventually leading to the discovery of the first exoplanets at the end of the 20th century.

In 1838, Wilhelm Friedrich Bessel determined the first reliable value for the distance between a star and the Solar System using the method of stellar parallax, measuring 0.314 arcseconds for the star 61 Cygni, which indicated that it is 10.3 lightyears away. This opened the door to the understanding of the true immensity of the cosmos. This method is now applied to the determination of stellar distances up to a distance of the order of tens of thousands of light years.

With spectral observations of Sirius showing a Doppler effect caused redshift in 1868, British astronomer William Huggins hypothesized that a radial velocity of the star could be computed.

The first astronomical application of photography was achieved in 1840 with an image of the Moon. In 1845 asteroids orbiting the Sun between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter were discovered. The element helium was discovered on the Sun in 1868. Helium had been unknown until then and was subsequently found on Earth. In early 1800s the eminent French mathematician and physicist Jean-Baptist Joseph Fourier calculated that the surface of the Earth was significantly warmer than predicted from the direct heating by the Sun. He thus, for the first time, recognized the role of the greenhouse effect in raising the temperature of the atmosphere. This was further elaborated on by John Tyndall, Irish physicist, who in mid-19th century identified water vapor and carbon dioxide as absorbers and stated: “Without water vapor, the Earth’s surface would be held fast in the iron grip of frost”.

An attempt was performed to measure the motion of the Earth relative to the luminiferous aether, a supposed medium permeating space that was thought to be the carrier of light waves. An optical experiment was performed between April and July 1887 by American physicists Albert A. Michelson and Edward W. Morley. As stated in its Wikipedia entry: “The experiment compared the speed of light in perpendicular directions in an attempt to detect the relative motion of matter, including their laboratory, through the luminiferous aether, or “aether wind” as it was sometimes called. The result was negative, in that Michelson and Morley found no significant difference between the speed of light in the direction of movement through the presumed aether, and the speed at right angles. This result is generally considered to be the first strong evidence against some aether theories, as well as initiating a line of research that eventually led to special relativity, which rules out motion against an aether. Of this experiment, Albert Einstein wrote, If the Michelson–Morley experiment had not brought us into serious embarrassment, no one would have regarded the relativity theory as a (halfway) redemption”.

In 1919 the gravitational deflection of light, predicted by the general theory of relativity of Albert Einstein, was confirmed by observation during a solar eclipse.

William Thompson, Lord Kelvin, was an eminent British thermodynamicist who flourished in the late 19th century. He calculated the age of the Sun to no more than 20 million years. At the time, the only known source for solar energy was gravitational collapse. Without sunlight, however, there could be no explanation for the age of the Earth estimated by both geologists and evolutionary biologists to be, at least, one billion years. This paradox was not resolved until the equivalence of mass and energy, one of the conclusions of Einstein’s special theory of relativity, was found, embodied in the iconic E = mc2 equation.

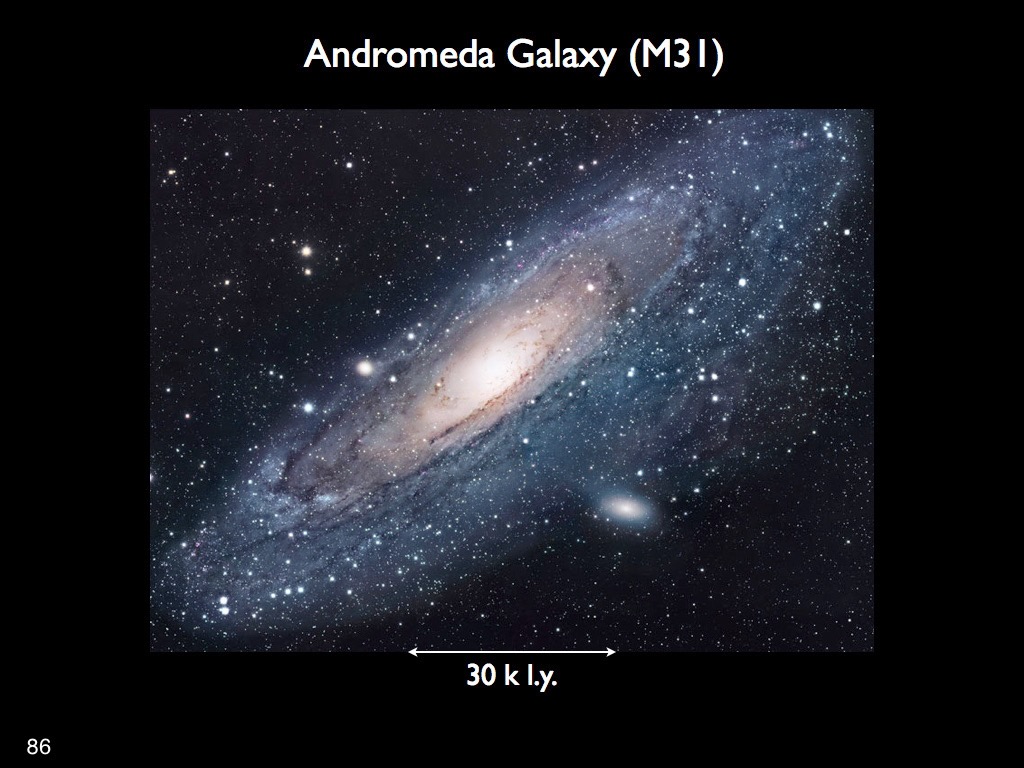

Edwin Hubble, an American astronomer published in 1924 his momentous discovery that the so-called nebulae, such as the one in Andromeda, were distant galaxies external and similar to the Milky Way which until then had been believed to be the entirety of the universe. Hubble had reached that conclusion based on the detection of Cepheid variable stars (see discussion about Cepheids further on) in the Andromeda galaxy. This crucial discovery settled The Great Debate, also called the Shapley-Curtis Debate, which was was held on 26 April 1920 at the U.S. National Museum in Washington, D.C. between the astronomers Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis. It concerned the nature of so-called spiral nebulae and the size of the Universe. Shapley believed t hat these nebulae were relatively small and lay within the outskirts of the Milky Way galaxy (then thought to be the center or entirety of the universe), while Curtis held that they were in fact independent galaxies, implying that they were exceedingly large and distant.

As described in Wikipedia: “Georges Henri Joseph Édouard Lemaître (17 July 1894 – 20 June 1966) was a Belgian Catholic priest, theoretical physicist, and mathematician who made major contributions to cosmology and astrophysics. He was the first to argue that the observed recession of galaxies is evidence of an expanding universe and to connect the observational Hubble–Lemaître law with the solution to the Einstein field equations in the general theory of relativity for a homogenous and isotropic universe. That work led Lemaître to propose what he called the “hypothesis of the primeval atom”, now regarded as the first formulation of the Big Bang theory of the origin of the universe”. Lemaître published these conclusions in 1927.

We must now give due credit to a notable woman astronomer in the context of the Cepheid variable stars mentioned above: Henrietta Swan Leavitt (1868 – 1921). She was a graduate of Radcliffe College and subsequently worked at Harvard College Observatory as a human “computer” analyzing photographic records of astronomical observations. This work led her to discover the relation between luminosity and period of Cepheid variable stars, what is now know as Leavitt’s Law. She made it possible for Edwin Hubble to make his crucial discoveries. Leavitt’s discovery became a standard candle to measure distance to other galaxies. The Cepheid method became the second rung (parallax being the first) in the cosmic distance ladder in the multi-step method astronomers use to measure vast distances in space by building upon different techniques for increasingly distant objects, with each rung confirming the one below it.

Full recognition for her important contribution to astronomy and astrophysics must go to Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin (1900 – 1979) who, being a woman, was denied a PhD at Cambridge and Harvard Universities but received a PhD from Radcliffe. Her thesis revealed the groundbreaking discovery that, in addition to elements commonly found on Earth, hydrogen and helium were the main constituents of stars. Her discovery led to the understanding of the thermonuclear processes within stars wherein their main sequence source of energy is generated by fusion of hydrogen into helium in their core.

Astronomy was the catalyst in the elucidation of other related questions in the physical sciences. We have discussed some of these and they will be restated here:

- Ole Roemer and the finite speed of light

- Newton’s law of universal gravitation and its role in space exploration

- The discovery of the greenhouse effect and heating of the atmosphere

- The Kelvin Paradox and the equivalence of energy and matter bearing on the age of the Solar System

- The Michelson-Morley experiment: aether’s absence and the nature of light

- Gravitation and its effect on light and all electromagnetic radiation

All the preceding progress that we have attempted to delineate, over the last 2200 years, from 300 BCE to about 1930, led to a truly stupendous expansion of humanity’s comprehension of the universe we inhabit. It involves a remarkable cast of characters that was involved in this quest of knowledge. Further, that remarkable — although not always linear — progression ushered in the spectacular advances that we have been witnessing over the last 100 years, a subject that falls beyond the scope of this essay.

A parting thought. This endeavor at summarizing the progress of astronomy from about 300 BCE to the 1920s was bracketed by two remarkable figures: Aristarchus of Samos and Edwin Hubble. If we were to attempt to proceed forward to the present, we would no longer be able to identify a single individual scientist who merits a similar mention. The lofty as well as increasingly complex undertaking of comprehending the cosmos is no longer the province of individuals. It requires the convergence of a multitude of scientists and observatories scattered worldwide. It would be very improbable that a single astronomer, cosmologist or astrophysicist would now be responsible of a major breakthrough in humanity’s understanding of our universe. I can cite a current extreme example of the collectivization of the cosmological endeavor: a paper published in 2024 on the results of observations of gravitational wave events, with the arcane title: “GWTC-3: Compact Binary Coalescences Observed by LIGO and Virgo During the Second Part of the Third Observing Run”. The paper is 82 pages long (nothing earthshaking about that), the contributing authors, however, belong to 297 different research organizations in 22 countries. But here is the truly mind boggling statistic: the total number of authors of this paper is…. over 1,500!

Slides