My early reading years were spent in Quito, the capital of Ecuador on the northwest of South America. I devoured books, all of them in Spanish, starting at age 9. Four authors predominated thereafter during my adolescence: Jules Verne, Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo and Karl May. The former three, French, and the latter, German. All those books were paperbacks, translations into Spanish, and were published in Argentina.

Each of these authors were widely read in their respective countries of origin and three of them, the French ones were, to some extent, read worldwide. Karl May was known mostly in German speaking countries.

It is worth pondering that there were no equivalent authors worth mentioning in the Hispanic world. I am referring to authors of the adventure genre that would appeal to a young readership. Of course there were brilliant early 20th century Spanish language writers such as Borges, Cortázar, Neruda, Martí, etc. but, in general, they were not those who would appeal to an adolescent reader.

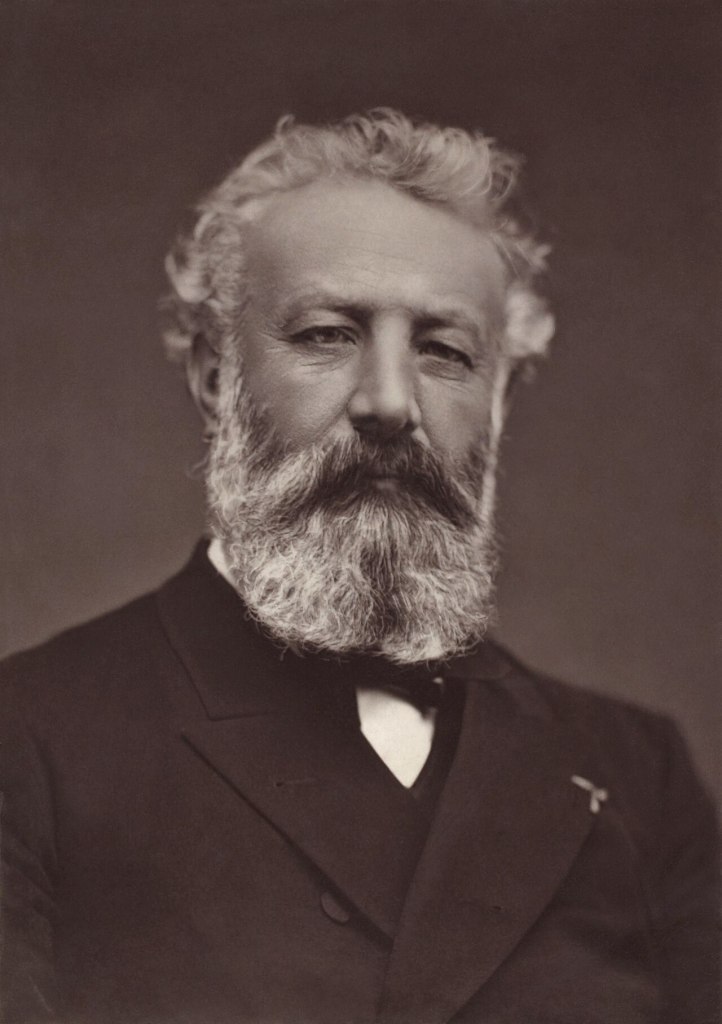

Jules Verne

Let’s start with Jules Verne, the first of the above mentioned authors whose science fiction novels From the Earth to the Moon and Around the Moon were given to me by my parents on my 9th birthday. It was my introduction to a lifelong involvement with astronomy and cosmology. Verne, who lived from 1828 to 1905, was a prolific writer whose output — contrary to a general perception — was not restricted to science fiction. In fact, that aspect was often incidental to many of the novels that Verne wrote.

What I derived most from Verne’s novels was the sense of adventure on a grand scale and, foremost, a knowledge of geography. Books like Les

enfants du Capitaine Grant (The Children of Captain Grant) which in its English translation is often named as In Search for the Castaways, awakened my awareness and understanding about the world. That book was the first of a trilogy succeeded by Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, culminating with what I considered the masterpiece of Verne’s oeuvre, The Mysterious Island.

I read, most probably, as many as twenty of his novels which ranged from pure science fiction to history to adventure. His imagination was boundless. One of the reasons why Jules Verne is not read or known in the U.S., as he should be, is that the translations of his books into English have been limited to some of his most famous books but, principally, because these translations have tended to be aimed purely at an infantile readership, omitting any scientifically inflected aspects. The English versions have, almost invariably, been degraded to appeal to the less educated as well as the intellectually incurious.

Last but not least, I narrated some of Verne’s novels to my children as bedside edutainment which, I believe, they still remember as adults.

Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas père (to distinguish him from his lesser known son, also a writer), lived from 1802 to 1870 and had a rather colorful ancestry. His father, General Thomas-Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie, was born in the French colony of Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) to Alexandre Antoine Davy de la Pailleterie, a French nobleman, and Marie-Cessette Dumas, an African slave. At age 14, Thomas-Alexandre was taken by his father to France, where he was educated in a military academy and entered the military for what became an illustrious career.

Dumas, was another prolific writer, successful with and admired by his contemporaneous readers. He had a colorful presence as (from Wikipedia entry) English playwright Watts Phillips, who knew Dumas in his later life, described him as “the most generous, large-hearted being in the world. He also was the most delightfully amusing and egotistical creature on the face of the earth. His tongue was like a windmill – once set in motion, you would never know when he would stop, especially if the theme was himself”.

I believe the first novel by Dumas that I read, and reread several times, was his most famous, The Three Musketeers, followed soon after by its first sequel Twenty Years Later. Then I discovered that there was a further continuation and finale entitled The Viscount of Bragelonne. I thus learned about the kingships of Louis XIII and Louis XIV, Charles I, Charles II, as well as about Oliver Cromwell, Richelieu, Mazarino, etc., a veritable education about 17th century France and England.

Then I read The Count of Montecristo, followed by several tomes on 16th century France, where I learned about the infamous Night of Saint Bartholomew, the famous surgeon Ambroise Paré and the even more notable anatomist and physician Andreas Vesalius.

The next historical sequence of several tomes by Dumas that I read was centered on Jean-Jacques Rousseau and the French Revolution. It led me to read The Confessions, an influential autobiography by that famous philosopher.

I learned much about French history as well as developed an early fascination about history, in general, by reading Dumas’s novels. By the age of 16 I was able to be dispensed from taking the final world history examination in 10th grade in my high school in Quito because of the knowledge I had acquired through my extracurricular readings.

As cited in Wikipedia, despite Dumas’s aristocratic background and personal success, he had to deal with discrimination related to his mixed-race ancestry. In 1843, he wrote the short novel Georges, which addressed some of the issues of race and the effects of colonialism. His response to a man who insulted him about his partial African ancestry has become famous. Dumas said: My father was a mulatto, my grandfather was a Negro, and my great-grandfather a monkey. You see, Sir, my family starts where yours ends.

Dumas has continued to inspire other present day, well known, writers such as the Spaniard Arturo Pérez Reverte.

Karl May

Not to be confused with the more famous Karl Marx, May, nevertheless was the most read writer in German literary history: at least 200 million copies of his works have been published, including translations into 30 languages. He is, however, largely unknown in the U.S.

Karl May lived from 1842 to 1012. His early life was that of a delinquent.

He was the fifth child of a poor family of weavers in Ernstthal, in what was then part of the Kingdom of Saxony. He had 13 siblings, of whom nine died in infancy.

As described in Wikipedia, in 1856, May commenced teacher training in Waldenburg, but in 1859 was expelled for stealing six candles. After an appeal, he was allowed to continue in Plauen. Shortly after graduation, when his roommate accused him of stealing a watch, May was jailed in Chemnitz for six weeks and his license to teach was revoked. After this, May worked with little success as a private tutor, an author of tales, a composer and a public speaker. For four years, from 1865 to 1869, May was jailed in the workhouse at Osterstein Castle, Zwickau. With good behavior, May became an administrator of the prison library, which gave him the chance to read widely. He made a list of the works he planned to write.

On his release, May continued his life of crime, impersonating various characters (policemen, doctors etc.) and spinning fantastic tales as a method of fraud. He was arrested, but when he was transported to a crime scene during a judicial investigation, he escaped and fled to Bohemia, where he was detained for vagrancy. For another four years, from 1870 to 1874, May was jailed in Waldheim, Saxony. There he met a Catholic Catechist, Johannes Kochta, who assisted May.

Eventually, May became a freelance writer, and later in life quite successful in the genre of adventure novels in what were then exotic lands. His best known novels are based on a first-person narrator-hero, the perfect German Superman with highly moralistic non-dogmatic Christian values which play an important role in May’s works.

It is of interest to note that in a letter to a young Jew who intended to become a Christian after reading May’s books, May advised him first to understand his own religion, which he described as holy and exalted, until he was experienced enough to choose.

My father, Erich, acquainted me with May’s novels which he had read in his youth. I was about 10 years old when I started reading May’s books and then devoured them. Again, I found Spanish translations of this oeuvre, available from the Argentinian publisher Sopena.

There were two groups of Karl May’s adventure novels. One was about the American West where he impersonated the inimitable Old Shatterhand, the heroic, invincible and morally driven German who becomes a blood-brother of the equally admirable Apache chief Winnetou.

My first exposure to the notorious Ku Klux Klan, which May despised, was through these novels. The other group of works took place in various countries of the Ottoman Empire where May is impersonated by Kara ben Nemsi, Karl the German, where he is accompanied by his faithful sidekick Hadschi Halef Omar through the Sahara desert and the Near East, experiencing many exciting adventures.

Many years later, during my professional life, my father would call me, mockingly, Old Scatterhand, a play on May’s Old Shatterhand, based on my work with light scattering.

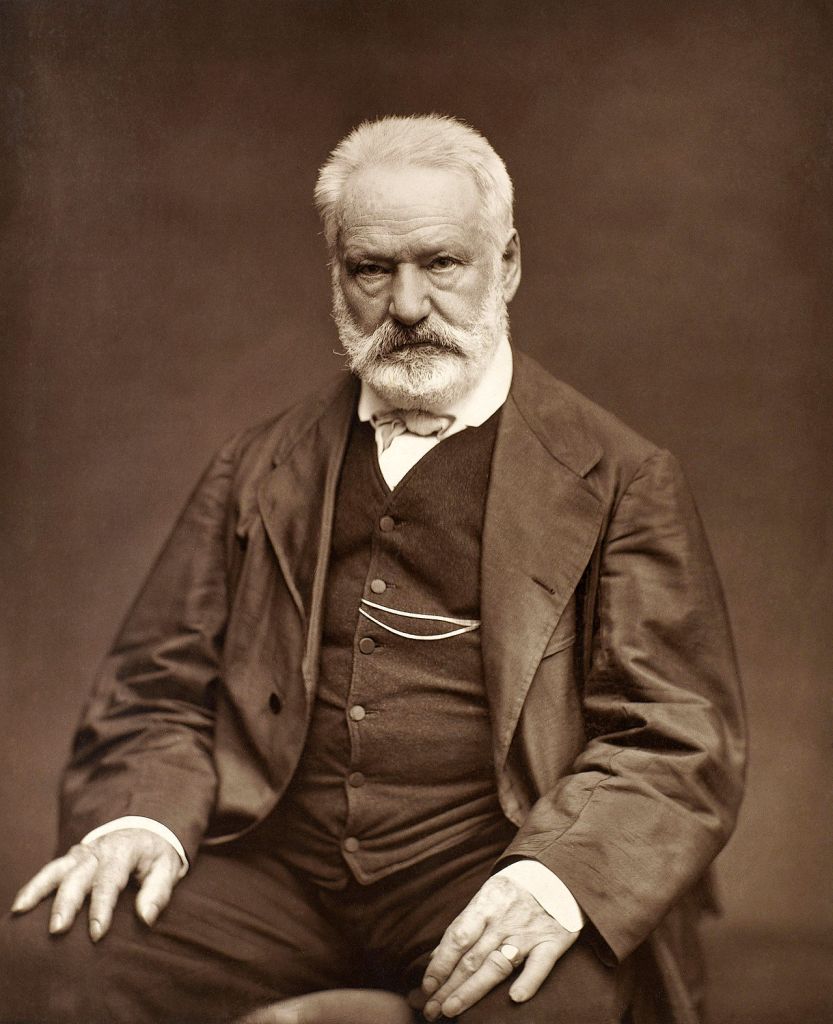

Victor Hugo

Victor Hugo was a French Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician. He lived from 1802 to 1885.

He was given a state funeral in the Panthéon of Paris, which was attended by over two million people, the largest in French history. The funerary procession extended from the Arc de Triomphe to the Panthéon, where he was buried. He shares a crypt there with Alexandre Dumas and Émile Zola.

The Hugo novels that I remember reading mostly had a social meaning of fate, justice and suffering. The first one I read was also his first: Han of Iceland, a somewhat strange gothic novel about a quasi-mythological evil human creature that ravages the island. Thereafter I read the staples of Hugo’s prose output: The Humpback of Notre Dame and Les Misérables. The latter one made a deep impression on me.

Other works I read were: The Man Who Laughs about the love of a disfigured man and a blind girl, The Toilers of the Sea about the lives of the fishermen of the island of Guernsey, and Ninety-three about the Terror during the French Revolution.

It is of noteworthy interest to mention that Victor Hugo wrote a play entitled Torquemada about Tomás de Torquemada and the Inquisition in Spain. It criticized religious fanaticism and fanatical catholicism. It was first published in 1882, as a protest against the antisemitic pogroms in Russia that were taking place at the time.

He became a non-practising Catholic and increasingly expressed anti-Catholic and anti-clerical views. Many of his works were placed on the Index of writings forbidden by the Catholic Church and in later years Hugo settled into a rationalist deism similar to that espoused by Voltaire.

A census-taker asked Hugo in 1872 if he was a Catholic, and he replied, “No. A Freethinker”.

Some Other Writers of My Teenage Years

After becoming aware of the Dreyfus Affair, I endeavored to read Émile Zola. However, I soon became disenchanted with the novels I read. I found that they pursued, too obsessively, human deviancy. Psychopathology permeated those writings.

I also attempted to tackle Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield which I abandoned half way through finding it too boring.

On the other hand I thoroughly enjoyed Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe as well as Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans.

I became very much intrigued by the dark writing of Edgar Alan Poe. I discovered Poe indirectly. I had come across Le Sphinx des glaces, The Sphinx of the Ice Fields, a two-volume novel by Jules Verne. Written and published in 1897, it is a sequel to Edgar Allan Poe’s 1838 novel The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket which follows the adventures of the narrator and his journey from the Kerguelen Islands. Neither Poe nor Verne had actually visited those remote islands, located in the south Indian Ocean, but their works are some of the few literary references to that forbidding archipelago. Poe’s narrative introduced me to the island of Nantucket which, later in life, I was to visit frequently.

Leave a comment