Paternal Ancestry

In our joint — my father’s and mine — autobiography, we mentioned the genealogy of our family. On my father’s side, the Lilienfelds went back to Siegmund, my great-grandfather, and on my grandmother’s (Julia Berl or Dola) side, to her parents, Bernard Berl and Julie Hertz.

Recently, googling my father’s name, Erich Lilienfeld, I came across a, to me, new genealogical website: geni.com. It revealed my paternal ancestry back to the 1700s.

I found the following patrilineal sequence: my great-grandfather Süßkind Siegmund Lilienfeld born in 1845, my great-great-grandfather Meier Meyer Lilienfeld, (1812-1883), my great-great-great-grandfather Michael Levie Lilienfeld, (1782-1849), and finally, Meier Levie, my great-great-great-great- grandfather, dates unknown, presumably mid-1700s.

Up to, and including Siegmund Lilienfeld, his predecessors were born in Gudensberg, a small community in the state of Hessen, central Germany. Isidor Lilienfeld, my grandfather, however was born in Frankfurt am Main, a major city, from where he moved to Merzig in the Saarland where my father was then born.

One particularly interesting conclusion can be reached from the above sequence of family names: the name Lilienfeld appears with the birth of Michael Levie Lilienfeld, in 1782. His father, Meier Levie, apparently, had not yet acquired or been given that gentile last name[1]. That year, 1782, coincides with that of the Edict of Tolerance for Jews issued by the Habsburg emperor Joseph II stipulating that Jews acquire a family name, among other requirements. Although the state of Hessen was not part of the Austro-Hungarian empire, it is most probable that these German principalities would have followed the example of the neighboring empire.

On my paternal grandmother’s Berl side, the ancestry is now as follows: my great-grandfather Bernard Berl (1841-1910), my great-great- grandfather Israel Isaak Berl (1814-1867), my great-great-great- grandfather Mathias Berl (1759-1843), and finally, my great-great-great- great-grandfather Isay Abraham Berl (1720-1822) who thus lived 102 years (!). The Berl family was ancestral to the Saarland and moved between Ponten and Merzig, adjacent communities in that state.

Maternal Ancestry[2]

As mentioned above, until the late 18th century or early 19th century, Jews in German-speaking lands generally did not have surnames. They were largely excluded from the commercial life of ordinary Christian citizens and were forced into petty trading or money lending. They could not own land, enter professions or the trade guilds, be publicly educated or be employed in any government position. They did, however, have other commercial advantages: they could read and write at a time when only the most affluent or the clergy were educated. They also had a wide network of trusted relatives and co-religionists with whom they could trade and exchange information.

It gave them wide access to knowledge and markets. Emperor Joseph of Austria recognized these skills and decided to integrate Jews into the economic life of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and so passed the Edict of Tolerance” in 1782, mentioned previously, just before the even more far-reaching French Revolution of 1789. This edict required that formal documentation was to be in German and that Jews would taken surnames considered acceptable to the authorities. These concepts spread across the German speaking lands. In 1812, towards the end of the Napoleonic era, King Frederick William of Prussia promulgated a similar law in which Jews living in Prussia became his subjects and citizens.

My maternal Anker family can be traced back to Jacob ben Salomon, who was born in about 1730 and died in the East Prussian town of Krojanke (now Krajanka in Poland) in about 1805. He was known by his Hebrew name Jacob ben (“son of”) Salomon as he would not, as a Jew, have had a proper surname at that time. We know that he had three sons: Aron ben Jacob, who was born in 1776 in Tuchel, West Prussia, Moses ben Jacob, born 1778 and Salomon ben Jacob, born in Krojanke in 1779. It is Ashkenazi Jewish custom not to name a child after a living forebear, but after a deceased one. It is likely that Jacob’s son Salomon was named after Jacob’s father who must have died in 1778. If he had died earlier, then Moses — the first born — would likely have been called Salomon.

It was thanks to the laws of King Frederick William of Prussia that Jacob ben Salomon’s sons Aron, Moses and Salomon took surnames. Clearly, they felt that this was a formality only for the Christian authorities and not for everyday life, as each chose very different surnames. Aron ben Jacob became Aron Jacoby, a derivative of the name of his father Jacob. Moses ben Jacob became Moses Holz. Holz is German for wood so one may safely assume that his trade was in timber, either as a merchant or a carpenter. Salomon took the surname Anker (my mother’s maiden name), which in German means anchor. Why Anker? As far as we know he lived all his life in East Prussia, away from the sea.

Three brothers with very different surnames; they could not have possibly imagined that within a generation they would, to a large extent, be integrated into non-Jewish society, even if mainly commercial, and that those surnames would become very relevant in their dealings with the world at large.

Alfons Anker

Also, in our joint autobiography, my father and I had mentioned a rather well known member of my maternal family: the Bauhaus architect Alfons Anker, older brother of my grandfather Erich Anker. Recently, I was able to acquire a book that describes his oeuvre as part of his association with two architect brothers, Wasili and Hans Luckhardt. The book is entitled “Brüder Luckhardt und Alfons Anker, Berliner Architekten der Moderne”[3] and was published by the German Akademie der Künste (Academy of the Arts) in 1990. The book describes in detail the life and oeuvre of this influential and pioneering group during the 1920s and 30s. The association between the brothers Luckhardt and Alfons Anker lasted from 1923 to the fateful 1933 when Hitler assumed power and my great- uncle had to resign from the firm on account of being Jewish. The Luckhardts were not, became members of the Nationalsozialistische deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Worker’s Party) and were thus able to continue their professional career throughout the Nazi years and beyond the end of the war.

My great-uncle, Alfons Anker, was the elder of the group having been born in 1872, in Berlin. In the words of his contributing biographer, Achim Wendschuh, he was “born into a home of a long established and wealthy family”. Following his graduation from the Berliner Oberrealschule (high school) he pursued studies at the Technische Hochschule, the same university from which my father, Erich, graduated a generation later. Anker then worked as an apprentice journeyman mason, a traditional German practical training stint. He completed his studies at the Höheren Technischen Lehranstalt (Higher Technical Institute) in 1893 after which he began his architectural career which he interrupted with an extended visit to Italy and Greece in 1902. He married in 1905 and had two daughters, and one son who was killed in Spain during the Civil War[4]. One of the

daughters, Annemarie Oehlmann, eventually moved to Sweden and married there.

Alfons Anker had already abandoned the Jewish Berliner community in 1920, converted to Lutheranism and had his affiliation to the evangelical church reaffirmed in 1933. This conversion and his apparent rightwing tendencies resulted in his alienation from his siblings. His brother Erich, my maternal grandfather, always spoke with disdain about Alfons, whom he called “der Fuchs”, the fox. Whereas my grandparents left Germany shortly after Hitler’s takeover, Alfons Anker was to leave only at the last moment, in 1939, when he emigrated to Sweden to join his daughter Annemarie. Apparently, he had intended to leave Germany since 1937 but found it difficult.

Once in Sweden, he was able to associate briefly in Stockholm with the architect Hakon Ahlberg. At the recommendation of several professors of the Technical University of Stockholm, King Gustav V awarded Anker the Swedish citizenship after a residence of only 5 years, instead of the normally required 10-year period. He was to publish Utlandspublicationen, an architectural journal. During the six Nazi years prior to his emigration, Alfons and his family had struggled to make ends meet by small remodeling and home addition projects, and by relying on previously acquired funds.

In Stockholm he pursues the field of hospital architecture and academic presentations on related subjects as well as publications in areas of public health architecture. After the war he reestablishes his links with the German Technische Hochschule (today’s Technical University of Berlin) where, in 1958 he was voted Ehrensenator (honorary Senator) shortly before his death at the age of 86, coincidently at the same age as his brother, my maternal grandfather.

Family and Life Expectancy

As I’m penning this, I have reached the respectably advanced age of 90. It induces me to write about my remaining time alive. I’m not sure how one is supposed to feel at my age but I believe that both intellectually and physically, I’m more fit than most people of my years. That judgment, however, is obviously subjective and may not reflect the opinion of everyone around me. In any case, I hope to make the best of the rest of my life, in spite of the unfortunate and unexpected burden of Evelyn’s mental decay.

Reflecting on my father, Erich, who died just 20 years ago, at the age of 97, I may survive another decade… or I may not. My recently implanted pacemaker indicates a remaining battery lifetime of 13 years, it’s likely to survive me. Unexpected health problems or accidents may shorten my life. I hope not. So far, I enjoy life too much to desire any early departure although a further descent by Evelyn into darkness may alter that. I would consider it unfortunate to miss the excitement of great scientific discoveries, of major technological advances, of gaining new intellectual insights. Equally, I do not want to miss witnessing achievements and happy milestones in the lives of my sons, grandchildren and other members of my small family.

I consulted various on-line sites dealing with life expectancies and found that on purely statistical grounds, i.e., based on the overall average of the U.S. population, I could expect to live another 3 1/2 years. Not great to be sure. When applying the specific criteria of my life style on the Lifespan Calculator of Northwest Mutual, however, I am given another 18 years (!) of life, i.e., to a near-biblical age of 108.

My family patrilineage may have bestowed us with, perhaps, a superior intellectual capacity. My paternal grandfather, Isidor Lilienfeld, seems to have been of rather superior intelligence, at least in the judgement of his widow, Dola, my grandmother. My father, Erich, must be classified as having been an unusually intelligent person. Myself, I’ll address that aspect further on. My sons, Claudio and Armin, are in my biased opinion, well endowed on that front. First indications are that their children are no intellectual slouches, either.

But I do not want to imply that our matrilineal members are of lesser intellectual caliber. My grandmother Julia Lilienfeld, Dola, was, to say the least, intellectually unusual. When I visited her in 1955, she was 80 years old, she discussed matters of acoustics, philosophy, and other subjects with me; she introduced me to Bartok’s string quartets, rather modernist music, inaccessible to many. My mother, Gerda, in her prime, proved to be enormously resourceful when our survival was at stake, as I have mentioned in my autobiography, and she was also a highly principled human being. Evelyn, from the time we first met attracted me as my intellectual equal and then throughout the first 60 years of our lives together.

Philosophically, as a nonbeliever, as a pragmatist, as a materialist and sceptic, I view life and, in particular, human life as a marvelous quirk of nature, and nature as a marvelous quirk of nuclear physics. The life quirk is an extraordinary gift to be enjoyed as long as it is worth enjoying. We are here without an ulterior purpose, without a fundamental raison d’être, a fleeting existence in a sequence of lifetimes of those who preceded us and those who will follow us.

We humans are an unlikely outcome of physical, chemical and biological phenomena, molded by evolution over hundreds of millions of years. As I have advocated in my recent essay Where Are We?, Where Are They?, mentioned previously, we, intelligent beings capable of technological communication, may well be alone, at least within our Milky Way Galaxy and, possibly, well beyond in the universe. Considering our potential uniqueness, planted on a trivially minuscule speck in an immense universe, it boggles my mind to contemplate the strife with which humanity has chosen to engage since time immemorial. Here we are, perhaps, unique beings endowed with the capacity to achieve almost anything imaginable and yet, finding every trivial pretext to hate and massacre each other. Will we be our own terminators? Are we destined to leave no trace in this lonely immensity? I once thought that if humanity survives the next 500 years, or so, we may have matured sufficiently to persist for an extended time, perhaps thousands of years. But, who knows, indeed?

How do I want to be remembered, once gone? Perhaps not at all, after a short period of de rigueur mourning. But if yes, then may be as a rather quirky, fairly intelligent, somewhat too self-centered with a slightly excessive ego, reasonably cultured, and rather consistently logical and rational individual.

In Memoriam of a Remarkable Person – Evelyn Tamara Landau de Lilienfeld

I am beginning to write this eulogy on July 15, 2023, presumably well before the actual passing of my dear Evelyn. I’m doing so now because of two reasons: her luminous presence is no more and a slow departure is underway, and yet she may outlive me physically.

I want to render her homage while I am still in full command of my mental faculties and capable of recalling details of our beautiful life together.

I want to talk about who she was during the long years of her mental completeness and brilliance. This will be an exercise that constitutes an auto-catharsis of sorts. It will give me solace to remember her as she was before her painful descent into darkness during the past three years. I need to dissipate from my brain this last period because it will help me to forget it and, rather, allow me to relive our many years of happiness together.

Evelyn was born on the last day of the year 1938 in Czernowitz in the region of Bukovina in what then was Romania. That city is now called Chernivtsi and is located in Ukraine. She and her Jewish family survived WWII in Romania, mainly because her father, Victor Landau, a lawyer, had influential friendships among Romanian gentiles. After the war, Evelyn and her family moved to northern Italy where they lived for four years. As refugees from a communist controlled country, they were given access to the U.S. where, at age thirteen, Evelyn arrived in NYC in 1951.

We met for the first time in October of 1958, in New York City when Evelyn was still to be a teen for another couple of months. I was 24 years old and a total greenhorn as far as meeting girls. Evelyn was in her senior year at Barnard College, notwithstanding her young age — she was to be a precocious twenty at her graduation in 1959. I had graduated in electrical engineering in Quito and was enrolled in graduate engineering school at Columbia U. Our meeting was a conspiracy between Evelyn’s father, Victor Landau, and a family friend, Moritz Scharfstein, who knew me from Quito. That latter connection is detailed in my autobiography. The circumstances of that first encounter could have raised Evelyn’s hackles were it not that we found immediate common ground in our multilingualism and European background. After starting with German, passing through French, our introductory conversation then converged on Spanish wherein it remained for the rest of our lives.

Our initial convergence, however, was not of the proverbial coup de foudre kind. Our mutual fondness grew gradually and accelerated by the time I returned home for the summer of 1959 vacation to Quito. Our three-month separation then solidified our mutual commitment, and by the time I returned to NYC we became inseparable. One of catalysts of that process was to be the remarkable parallels we found in our life’s experiences: our European background, the cosmopolitanism of of our families, our peripatetic wanderings and, last but not least, both our mother’s emotional and mental problems.

In June of 1949, Evelyn graduated with a BA from Barnard with cum laude. She had deserved a magna cum laude were it not for a single professor who had made her student life difficult.

During my absence in Quito we bombarded each other with interminable letters solidifying our relationship. When I arrived back in NYC in September of 1959, Evelyn received me at the airport in a summerly polkadot dress exposing her bronzed shoulders. I was thoroughly smitten. Our mutual attraction had been completed emotionally, intellectually and, not the least physically. By February 19, 1960 we very married.

During our extended getting-to-know each other, I became acquainted with Evelyn’s intellectual heft. She was not only cultured but her intelligence made her interested in a wide range of fields. She was mesmerized by my deep involvement with astronomy and other sciences. She was open to new ideas, she was thoroughly unprejudiced. Frequently we took interminable walks together in Manhattan, along the West Side Drive, crisscrossing Central Park, along the avenues, etc., all while exchanging experiences, sharing ideas, talking about cosmology, history, languages, philosophy and family.

When I first met her she was fluent in six languages: English, Spanish, French, German, Italian and Polish. In her childhood she had also spoken Rumanian and Hungarian, and recently had taken up Russian at Columbia U. She had an accent, an idiosyncratic one, and only in English; all other languages she spoke accentless. I felt outclassed on the multi linguistic front. That uncanny ability was to serve her well in future years. In fact, she had secured a fellowship at the United Nations translation school in Geneva but decided to forgo it because of our evolving relationship.

Before proceeding with an exegesis of Evelyn’s married life, I need to backtrack and acknowledge the difficult life that she had endured, mostly as a teenager, before we met. That experience was to affect her for the rest of her life. Her mother, Erika Landau, suffered from recurring bouts of depression that had begun in Europe, prior to her arrival in the U.S. She became largely dysfunctional, especially as a mother to Evelyn and a burden to her daughter when she most needed a motherly presence. Evelyn’s father, a good natured and gregarious person, failed largely as a father as he was frequently absent from the home environment because of his strenuous efforts to be an effective breadwinner for the family, and because he, too, had difficulties coping with his wife’s dysfunctions. Evelyn, nevertheless, was utterly attached to her father as he had been her only stalwart, although imperfect, support during most of her life.

Even before Evelyn and I were married I had to provide moral support to her as a sounding board and adviser, and that role was expanded thereafter. I always accompanied her when she needed to visit her mother at various hospitals to which she had to be confined. We had to witness together the effects of electric shock treatments to which she was subjected at Bellevue Hospital in NYC, a then rather barbarous procedure that reduced the patient to a nearly vegetative mental condition. Evelyn’s mother was confined to a suburban mental treatment facility when two sad events sequenced each other in 1965: first the passing of Evelyn’s grandmother in the spring, followed a few months later by the shocking and unexpected death of her dear father by a violent heart attack that felled him on a street in mid-Manhattan. I had to identify the body in the morgue. Evelyn and I had the unenviable mission to eventually communicate that news to her confined mother. That loss was to be emotionally overwhelming for Evelyn and it took several years for her to recover. More than half a century later, she still cited the death of her father as a perennially unsettling shock.

The birth of our two children, Claudio and Armin, brought a measure of relief and distraction to Evelyn’s emotional turmoil. Mothering demanded her full attention and dedication. This activity required a certain readjustment for her. She had no experience with interactions with children and her intellectual focus was largely academic. She needed to transition from a dedicated and assiduous college student to being a motherly caregiver. It took a bit of time but she rose to the occasion with flying colors. In fact, I attribute the success of our children’s upbringing and subsequent adulthood to the utter and effective dedication that Evelyn evinced with the patience, understanding, love, guidance, care and nurturing that she brought to that task. I consider that my role in that endeavor was merely ancillary.

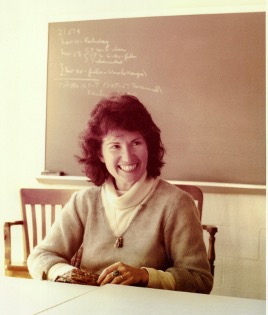

Our move from New Rochelle to Lexington was, to some extent, a liberation for Evelyn. It helped her to separate from the NYC environment that had carried mostly a memory of unhappiness for her. Our new Lexington house, with its beautiful natural surroundings was to be truly cathartic. Very soon her latent intellectual penchant found a channel of expression, initially, in a modest stint as elementary school French auxiliary teacher. It was to be the start of a new career, one in which she flourished. She had been timid and reticent when I had first met her, but teaching allowed her inner self to surface and shine, giving her a self-assurance that had been previously lacking.

The next, and most significant step in her professional teaching career was, of course, the result of an oft recounted chance encounter with Mary Lewis Weaver — later ML Grow — in a Lexington supermarket. ML overheard Evelyn talking in Spanish to one of our sons whereupon he responded in English. That unusual interchange peeked her curiosity, a

conversation followed, and eventually Mary Lewis became her introductory bridge to lectureships in Italian and Spanish at Tufts U. where Evelyn taught for several years, a jump from elementary to college teaching, attesting to her mental agility. Subsequently, an opening at MIT to teach Spanish offered her an even more challenging and rewarding experience. She was to remain as an instructor there for 17 intensive and satisfying years. She truly flourished in that high power academic environment being the sole faculty member of her Romance Languages department with only a college education. Her unusual language ability was complemented by her intelligence and cultural power that lent a special allure to her teaching, and this was fully recognized by the other members of her department.

Evelyn acquired an uncanny proficiency in the intricacies of Spanish grammar. She had had no formal training in that discipline but absorbed that knowledge simply through exposure and awareness as she

progressed in her teaching. This capability reached the level where she was able to correct me, a native Spanish speaker, when I infringed some rule by using a vernacular Ecuadorianism.

She was very popular as a teacher at MIT and her true talent was uniquely demonstrated during the so called Independent Activities Period (IAP) that

was offered during the month of January every year. For a period of four weeks students and faculty could attend one of several intensive courses, among which were intensive Spanish. It required teaching for several hours a day for five consecutive days every week, an exhausting commitment. I attended a party given to the students, who include several Institute deans,

after completion of one of these concentrated courses and I was astonished at the remarkable level of proficiency that the students had attained; I was able to fluidly converse with them in the language of Cervantes. To further attest to the effectiveness of Evelyn’s teaching, I came across a letter by a student, Jon D. Morrow ’85, published in The Tech, a weekly student newspaper of MIT, of Tuesday, February 7, 1984 that read, after registering concern about the planned discontinuance of these intensive language courses, the following:

“Last year I was enrolled in IAP Intensive Spanish, taught by Evelyn Lilienfeld. The following summer, while on duty at the Massachusetts General Hospital emergency ward, I was able to interpret for a Colombian patient who spoke no English. The Spanish that I had learned from Lilienfeld five months before was more than sufficient for translating the doctor’s and patient’s answers. I believe that I would have neither absorbed nor retained enough Spanish for these translations had I taken an ordinary subject spread over several months.”

Evelyn thrived in the high powered environment of MIT and found the students remarkably committed and capable, compared to those she had taught at Tufts. She retired from MIT in 1996 as the Institute offered an advantageous retirement package, and Evelyn wanted to dedicate herself

to another endeavor in which she became uniquely successful: planning and undertaking voyages to other countries.

From the beginning of our relationship, Evelyn repeatedly expressed a profound longing to return to Europe. This reflected, to some degree, her unhappiness during the first few years in the U.S. The itinerary of our honeymoon trip was based on that deep desire to reconnect with the old country of which she was so fond, especially Italy. Her happy memories of Florence, Milano and, in particular, Merano in the Dolomites had remained with her.

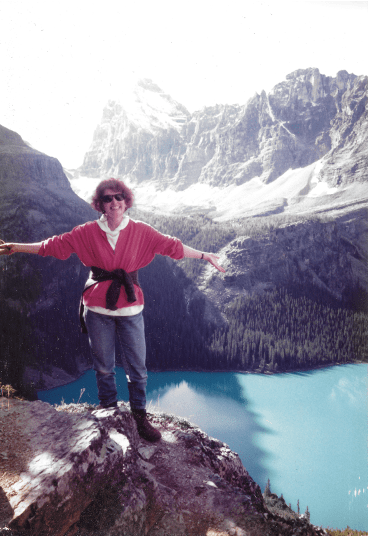

Our first major trips, however, were of the camping type, and in the U.S. and Canada. This was dictated by our financial constraints. Nevertheless, Evelyn came to love those adventurous expeditions with our young children. She thrived in the natural environment and very much enjoyed the

hiking challenges, especially in the Canadian Rockies. Even when we were hiking in the West, Evelyn could be at her elegant best when we stayed at the Post Hotel in Lake Louise. She always shone with poise, beauty and elegance at the appropriate venue.

Eventually, we were able to afford voyages across the Atlantic, to her old Europe. At first we undertook trips that were supported by my professional endeavors. Starting in 1981, however, we were able to afford purely leisure vacations in Europe which Evelyn planned meticulously. She was particularly adept at reading and researching guide books, and newspaper and travel publications, while also communicating directly by telephone with prospective hotels and inns, in each of the languages spoken at a given target country.

For a while we concentrated on France but soon extended our objectives to Spain, Italy, the UK, Austria, Switzerland and Poland. Her talent to

select interesting places, good lodgings, great sites, etc. were unfailing. Essentially all of our European trips were highly successful and satisfying.

Starting in 1982, Evelyn and I embarked in several pilgrimages in France, Spain and Italy seeking medieval cistercian/romanesque architectural gems. This was spurred by the art classes that she was taking. This pursuit culminated with an automotive trip following the Camino de Santiago in northern Spain, where we visited even older sanctuaries, going back to Visigothic times.

Eventually, starting mainly in the 21st century, Evelyn extended our travel reach to other continents. Perhaps she got a taste of such forays accompanying me on a professional trip to Japan in 1990 and a short visit to Israel. Once our finances allowed it, Evelyn organized trips to far

flung and exotic destinations: Jordan and Egypt, Turkey, Morocco, southeast Africa, and India.

She had also contributed in organizing several trips to South America, the Caribbean and Costa Rica. She always rose to the challenge to select the best travel organizations, countries, sites, inns and itineraries.

Her engaging personality, warm demeanor, genuine interest in her surroundings and humane and understanding treatment of those with whom she interacted during our travels made her welcome and loved by all. I sometimes felt like a mere appendage to her luminous presence.

Back home, in Lexington, Evelyn was the motivator and organizer of a book club of likeminded women friends, another of her intellectual outlets. More academically, and over a period of several years, she attended a number of courses in history of medieval art under the auspices of Harvard and Lesley U. which took her on a cultural class excursion to northern Italy.

For many years, Evelyn enjoyed my reading aloud to her. She would listen attentively and commented on the subject at hand. Sometimes when reading to her in bed in the evening, she would quietly go to sleep….

Evelyn read profusely as long as her mental faculties allowed it. Her eventual reading cessation was a most painful reminder of her mental descent. It really meant that I had lost all of her warmth, her brilliant intellectual presence that I had enjoyed so much over such a long time. We had been able to converse, sometimes animatedly, about so many subjects, whether about the Crusades and the Iberian Reconquista, our shared life experiences, comparative language idiosyncrasies, astronomy’s advances, biology and evolution, politics, religion, our travel experiences, etc., etc….. All of this is now gone!… What a shame!…So disheartening!….

What remains, however, is the incised memory of her prime, her uniquely beautiful smile and her intense presence to which I, desperately, cling and don’t want to let go until I, myself, be gone.

Farewell, my love!

Added on December 11, 2024, the day after Evelyn died:

My Mausi Is Gone!

The rain is pouring, the night is dark, my dog Gaia is suffering, she has an abscess, I’m alone with myself, with my emptiness, and I’m crying.

My Mausi is gone!

Her smile and warmth left me months ago. Yesterday she departed altogether. Her beauty and her dazzling smile have been extinguished. Only her memory remains and that is not enough. Give me back her dancing self, her warmth, her intelligence, her enterprising spirit, her happiness, her love….

My dear Mausi is gone!!!

[1]Lilienfeld is a gentile name: an Erich Lilienfeld was a German commander of a U-boat in WWII, he died at age 27 when his submarine was sunk in mid-Atlantic in 1942.

[2] The information of this section was provided by George Fogelson.

[3] Brothers Luckhardt and Alfons Anker, Berliner Architects of the Modern

[4]I found no further information about this son’s participation in the Spanish Civil War.

Leave a comment