For several years we have been exposed to the deluded idea that humanity must travel bodily to, settle on, and colonize other bodies of our Solar System, specifically those two on which we can land without being fried or swallowed, i.e., the Moon and Mars.

It should be noted that I have a long association with this matter. I treated the possibility of human travel to those two extraterrestrial objectives in a short paper in Spanish, published in 1957 by the National Polytechnic Institute of Ecuador where I was a student, entitled Viajes a Otros Planetas (Travels to Other Planets). It was my first published paper. Therein I also considered the planet Venus as a possible target of human exploration, reflecting our ignorance, in the mid-1950s, of its hellish high surface temperature and pressure.

Settling humans, especially on Mars, has been and continues to be justified for several reasons, principally, among them, humanity’s perennial drive to explore and, more recently, a purported existential need to expand out of our planet Earth. The former of these is supported by our long history of expanding into the unknown corners of our planet. The latter justification is based on the perception that we are likely to exhaust Earth’s resources and thus the need to find other material sources as well as extraterrestrial abodes for an ever-growing humanity, a newfangled version of Mussolini’s early 20th century drive to expand the spazio vitale, the vital space, in this case, of humanity at large.

In the U.S., there are various forces in support of interplanetary expansion. On one hand NASA, in part, to justify its own existence and to receive a vast amount of government supplied finances. On the other, multibillionaire dreamers, such as Elon Musk, for reasons of self-aggrandizement and puerile entertainment.

Mars, of course, has been the focus of long-term fascination as it was believed, during the 19th and early 20th centuries, to be the abode of an advanced alien civilization, especially as manifested by a purported system of canals on its surface. At present Mars is being explored in detail by several means, such as orbiting craft, surface rovers and a mini-helicopter. Past presence of liquid water makes this planet a potential harbor for fossilized basic life forms, although none have been found, as yet (2024).

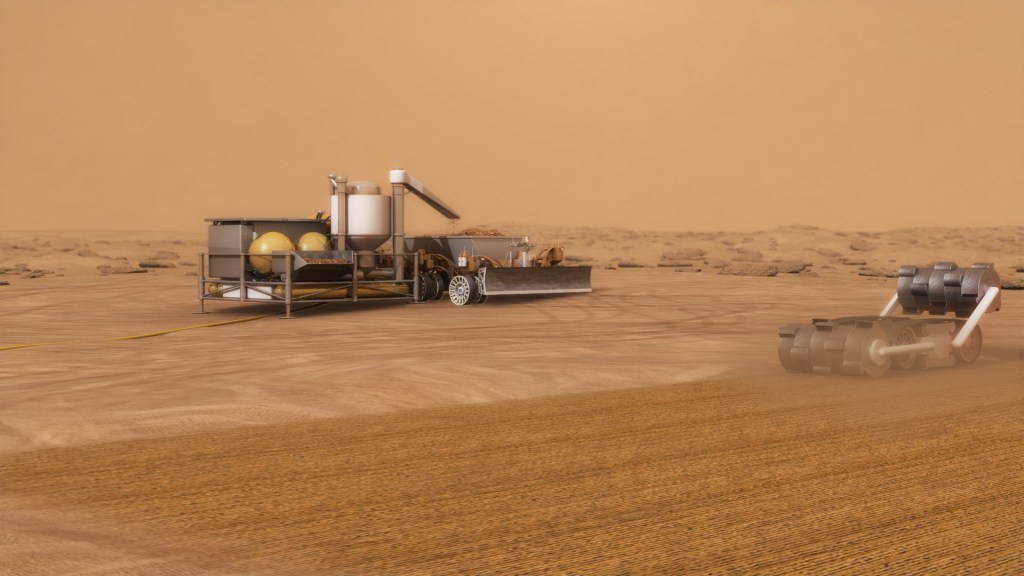

What makes Mars attractive as a human landing objective? Several factors contribute: relative closeness to Earth, bearable surface temperature, possible accessibility to water, although mostly frozen, and potential presence of useful minerals.

Negative aspects of the red planet? Unfriendly atmosphere: extremely tenuous and non-respirable and imperfect as meteor shield, and occurrence of frequent and intense dust storms. The absence of a global Martian magnetic field creates a potentially lethal radiation environment requiring rigorous shielding of human explorers.

So, why am I so adamantly opposed to manned missions to Mars? For several reasons which I will discuss in what follows.

First of all, I consider the reasons that have been adduced against such endeavors.

- No new scientific insight that we cannot gain from robotic probing would be expected. NASA is even presently pursuing a special mission for the retrieval and transport to Earth of a Martian soil sample which will then be analyzed here in depth.

- The need to explore new frontiers hardly justifies the enormous effort that manned travel to Mars entails. We have not even fully explored the depths of our own submarine worlds.

- The Martian environment is inhospitable to human occupation and can hardly be considered adequate “vital space” to be expanded into.

- Establishing Martian settlements would inevitably be accompanied by the usual despoliation of that new world that would result from the disposal of waste and pollution produced by the “colonists”.

- The cost of a round trip manned mission to Mars would be exorbitant. An amount such as one quadrillion dollars has been mentioned. Judging from past experiences with complex space projects, any initial estimate can be expected to be exceeded multiple times. Humanity’s financial expenditure priorities lie elsewhere.

In addition to the above listed arguments we should consider the risks, both known and unknown, that the crew of a Martian mission would be facing. We have two types of experience to consider for such endeavor: the Apollo astronaut missions to the Moon of the 1970s and the extended spaceflights on board of the International Space Station (ISS).

The Moon missions were of relatively short duration. It takes about three days to travel to our natural satellite. A voyage to Mars entails an entire year. Most of these Moon landings were largely uneventful, except for Apollo 13 which almost ended in disaster and had to be aborted as a result of the rupture of an oxygen tank.

As to the long term stays on the ISS, it is enlightening to cite the detailed description of a yearlong trip by the American astronaut Scott Kelly in his very insightful book Endurance (2017). It should be noted that this very title informs us about the fraught experiences of such an endeavor, even though this type of voyage takes place in Earth’s immediate vicinity, merely 250 miles above the home planet. Here are some specific observations by Kelly in his book that should be considered with respect to a manned trip to Mars:

“Our space agencies won’t be able to push out farther

into space, to a destination like Mars, until we can learn

more about how to strengthen the weakest links in the

chain that makes spaceflight possible: the human body

and mind”.

“If we are going to get to Mars, we are going to need a

much better way to deal with CO2 . Using our current finicky

system, a Mars crew would be in significant danger”.

“The toilet is one of the pieces that gets a great deal of

attention—if both toilets break we could use the Soyuz

toilet, but it would not last long. Then we would have to

abandon ship. If we were on our way to Mars and the toilet

broke and we couldn’t fix it, we would be dead”.

“I also know that if we want to go to Mars, it will be very,

very difficult, it will cost a great deal of money and it may

cost human lives”.

We must take into consideration a very important potential and likely hindrance to a manned Mars mission: what I would like to call the problem of isolation, i.e., the fact that once the astronauts are underway they will be on their own; no physical contact with Mother Earth will be possible. There cannot be any resupply, maintenance support, replacement of materials, and foremost, no possibility of evacuation in case of serious crew illness.

Scott Kelly mentions the reliance of the functionality of the ISS on frequent resupply from the Earth by means of rockets and the crises resulting from their failures to reach the space station. As to health-related crises, it is pertinent to mention the recent case of the sick researcher who had to be rescued from the Antarctic requiring an urgent and precarious evacuation to Australia. No such recourse would be available to Mars bound astronauts.

In addition to physical obstacles discussed above associated with the isolated condition of a manned Mars expedition, we have to consider the potential mental and psychological burden imposed on such astronauts. NASA is pursuing a program labelled Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog (CHAPEA) which “is a series of analog missions that will simulate year-long stays on the surface of Mars. Each mission will consist of four crew members living in Mars Dune Alpha, an isolated 1,700 square foot habitat. During the mission, the crew will conduct simulated spacewalks and provide data on a variety of factors, which may include physical and behavioral health and performance”.

This program is well intentioned and yet largely irrelevant as far as simulating the spatial isolation endured in a real mission to Mars both during the flight and the stay on that planet. These crew members of CHAPEA obviously know full well that they can count on instant help and support in case of need, as they are not isolated millions of kilometers away from that support or any other external recourse. Even if no need for support should arise during a simulated mission, its constant and instant availability provides a totally unrealistic measure of reassurance absent during a real Mars mission.

An additional source of psychological discomfort arises from the roundtrip communication delay of up to about 40 minutes, a result of the distance separating Mars from the Earth which at conjunction — greatest distance, when Mars and the Earth are on opposite sides of the Sun — reaches about 380 million kilometers. Furthermore, for approximately two weeks, at and around the time of conjunction which occurs about every two years, a communication blackout between Mars and the Earth can be expected, as the Sun’s corona interferes with radio transmissions.

To compare the voyages of discovery of the 16th through the 19th centuries with a human exploration of Mars is disingenuous. It ignores the entirely different environment that awaits humans on Mars. Its unforgiving atmosphere dictates the use of cumbersome space suits whenever the earthlings exit their landing craft. The radiation exposure, mentioned above is, to date, an unsolved problem.

We should keep in mind that Homo Sapiens is the result of more than 200 million years of mammalian evolution, not even considering the eons of the preceding evolutionary path. This evolution has been constrained to the Earth’s surface and its environment. As a result, we are constructed to live in a gravitational field of 9.8 m/s2, or one g, an atmospheric pressure around 105 kg/m.s2, or one atmosphere, with a composition of mainly nitrogen (78%) and oxygen (21%), and a radiation level of the order of 2.4 mSv per year.

In comparison, on Mars the gravitational field is about 3.7 m/s2,

the pressure is merely 610 kg/m.s2, with a composition of mainly CO2 (95%), and a radiation level of about 270 mSv per year, i.e., significantly higher than on Earth. In addition, we must consider the potential danger posed by meteorite strikes on Mars which is much higher than on Earth, as a consequence of the tenuous atmosphere of the red planet and its vicinity to the asteroid belt. In summary, there are several factors that make Mars an unfriendly abode for earthlings.

During the year long, or so, flight to Mars the astronaut explorers would be exposed to zero gravity and to a radiation level far in excess to that experienced in near-Earth orbit as experienced so far by the crews of the space station. Once on Mars the astronauts would be exposed to decreased gravity but also to the enhanced radiation level. A host of physiological problems would thus be expected to arise. Much has been written about these health effects and I will limit myself to mentioning only the most salient ones. Long-term exposure to weightlessness causes multiple health problems, one of the most significant being loss of bone and muscle mass. In fact, astronauts who have returned from long-term missions on the space station, have required physical support by the recovery crew, even to stand up. This raises the prospect that, on arrival on Mars the intrepid space voyagers would be nothing but near cripples facing daunting and immediate physical tasks. In addition, extended weightlessness reduces aerobic capacity, and slows down their cardiovascular system. NASA scientists have reported that a possible human mission to Mars may involve a great radiation risk based on the amount of energetic particle radiation detected on the Mars Science Laboratory while traveling from the Earth to Mars in 2011–2012.

More recently (2024), a study found that Mars missions may be hindered by kidney stones which apparently are caused by low gravity combined with high radiation exposure. Another study determined that severe liver damage is likely to arise for similar reasons.

In my opinion, there are far more worthy ways in which our space community can direct its efforts and financial resources, such as the robotic exploration of the moons of Jupiter, Saturn and even Uranus and Neptune. And there are many other justifiable space endeavors to be pursued.

I would like to cap off my opposition to a human crewed Martian folly by citing two supporting views on this subject. One is a review in the Boston Globe (April 27, 2024) of the recent book by the well known science writer Elizabeth Kolbert, entitled “H Is for Hope: Climate Change from A to Z”: H Is for Hope: Climate Change from A to Z

“Scratch Mars off your list of climate change solutions. No matter what happens on Earth’s climate system, our home planet is the best shot the human race has for survival. Fantasies about vast populations of people living on Mars are a distraction from the real and present danger facing our planet. Earth, for all its problems has breathable air. Not something you can say for our planetary neighbors. ‘We evolved to live on Earth. Really almost no matter what we did, it would still be an easier place for humans to live on than Mars’, she said. ‘Because (on Mars) there’s no air pressure. Now imagine living with no air pressure. Your full body would explode. So you can’t go outside. It’s basically insane to think we can live on Mars’”.

The second opinion I want to cite against manned flights to Mars comes from an even more authoritative source: the eminent American physicist Steven Weinberg (1933-2021), winner of the 1979 Nobel Prize and arguably the most prominent physicist on the last 50 years. He devotes almost an entire chapter of his book of essays entitled Lake Views (2009) to an impassioned exhortation against sending people to Mars in a chapter aptly entitled The Wrong Stuff. Therein Weinbergpresents his opposition to such an endeavor citing its exorbitant cost and the lack of scientific justification underlying such missions. He bemoans the deployment of the International Space Station as an example of distorted expenditure priorities; the ISS’s high cost came at the expense of the Superconducting Super Collider, a crucial tool in the study of high-energy physics that was cancelled in 1993.

Weinberg, among other arguments against manned space flights to remote targets states pointedly:

“I hope that one day men and women will walk on the surface of Mars. But before then, there are two conditions that will need to be satisfied. One condition that there will have to be something for people to do on Mars that cannot be done by robots. If a few astronauts travel to Mars, plant a flag, look at some rocks, hit a few golf balls, and then come back, it will be a thrilling moment, but then, when nothing much comes of it, we will be left with a sour sense of disillusionment, much as happened after the end of the Apollo missions to the Moon. Perhaps after sending more robots to various sites on Mars something will be encountered that calls for direct study by humans. Until then, there is no point in people going there”. Amen!

Addendum: October 16, 2024, column in The Angeles Times by Michael Hiltzik, entitled: “Elon Musk’s Dumbest Idea is to Send Human Colonists to Mars”. The column’s concluding sentence is: “Our imperative is to fix the home we live in before setting forth to ruin another one”.

Leave a comment