When Armin, my younger son, was about 2 1/2 years old, I remember distinctly that as he looked out of our living room window in New Rochelle, NY, one evening, he saw the Moon, pointed at it and asked: “Moon not fall down?”. With a mixture of fatherly pride and surprise I tried my best at reassuring him about the Moon’s stability while making a vain attempt to explain Newtonian gravitation to a precocious toddler.

Recently (2017), in perusing volume 1 of Albert Einstein, Philosopher-Scientist, a classic 1951 compilation of writings about the famous scientist by several of his contemporary luminaries, including an autobiographical section, I found Einstein’s following childhood reminiscence:

“A wonder of such nature I experienced as a child of 4 or 5 years, when my father showed me a compass. That this needle behaved in such a determined way did not at all fit into the nature of events, which could find a place in the unconscious world of concepts (effect connected with direct ‘touch’). I can still remember – or at least believe I can remember – that this experience made a deep and lasting impression upon me. Something deeply hidden had to be behind things. What man sees before him from infancy causes no reaction of this kind; he is not surprised[1] over the falling of bodies, concerning wind and rain, not concerning the moon or about the fact that the moon does not fall down, nor concerning the differences between living and non-living matter.”

What a discrepancy between my son’s quizzical query and Einstein’s view!? Did the great thinker “miss the boat”? Did little Armin prove him wrong? I venture a likely explanation for this disparity: A child, by the age of 4 or 5 years — Einstein’s recollection — may no longer be surprised by those phenomena that he/she has witnessed repeatedly (e.g., the suspended appearance of the Moon), but at an earlier age (2 1/2 as in the case of Armin), when awareness about the world is just awakening, such phenomena can still elicit surprise and questioning. Einstein’s puzzlement by the behavior of a compass needle at age 4 or 5 can easily be explained because he had not been exposed previously to that phenomenon whereas the suspended Moon was already familiar to him.

That brings up a more general problem that is common to humanity. Our growing inability and unwillingness to be aware of nature and to query its behavior and phenomena. Since we were on the subject of the appearance of the Moon, the vast majority of us will certainly not be puzzled by its apparently immutable suspension in the sky, either for lack of interest or attention, or because we are knowledgeable enough about the underlying physics.

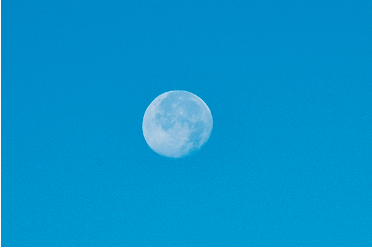

But, I have a pet Moon issue that essentially never elicits questioning and yet is rather obvious. When the Moon is visible during the day, against a blue sky background, its color is whitish and stands out clearly. Now, the blue color of the daytime sky originates in front of the Moon, within our atmosphere; the Moon is way above and beyond that atmosphere. So, why does it look as if the moon is in front of the blue sky? Have you asked yourself that question? The answer to this apparent contradiction resides in two fields of knowledge: physics and physiology. The blue color of the sky is the result of solar light scattered in our atmosphere by gas molecules whose size is much smaller than the wavelength of that light. That combines with the fact that our eyes are much more sensitive to white light than to blue light, and evolutionary trait. So, the blue light from the atmosphere in front of the Moon is overwhelmed by the white sun light reflected by the moon. An attentive observer may notice that the the lunar mare – the darker patches one sees on the Moon – appear bluish because less white light is reflected off those areas (see photo of the Moon above).

There are many such physical effects to which we are exposed on a daily basis and which do not elicit curiosity and questioning. Many of us tend to go through life blithely unaware and/or uninterested in our surroundings. I can think of examples of two such phenomena. The first is the acoustic Doppler effect: when an airplane passes nearby, especially a jet plane overhead, the pitch of the sound we perceive drops as the plane nears and then leaves our vicinity. The same happens if a police or fire engine sounding its siren passes by. The effect is rather dramatic but seldom, if ever, noticed, and it is caused by the stretching of sound waves from a source that moves away from us. This same Doppler effect also applies to light waves and was the basis for the discovery of exoplanets.

Another, perhaps more esoteric effect, but nevertheless pervasive, is the Coanda effect. It occurs every time that you pour a liquid out of a bottle, the liquid tends to adhere to the bottle. It is the tendency of a fluid flow to stay attached to a convex surface. It is easily demonstrated by placing a finger along the outer surface of water flowing out of a faucet, the stream then adheres to your finger and you can thus deflect the flow.

[1] My emphasis

Leave a comment