In February of 2007 Evelyn and I travelled to the Middle East for the first time and this is a summarized travelogue of that trip

We just spent almost three stupendous weeks in the Middle East, specifically in Jordan and then Egypt. We would like to share some of the salient – as well as trivial – impressions we had during that sojourn.

We had originally planned a trip to Egypt for October 2001 which we promptly cancelled in the immediate aftermath of 9/11. As time passed we reconsidered such a visit not withstanding the reservations about such a trip to a region identified with strife, danger and the perception of growing – and largely justified – unfriendliness towards the U.S. caused mostly by our unsupportable invasion of Iraq. Being, as we are, a bit contrarians when it comes to such perceptions, and considering the opportune time to go when others might be reluctant to do so, we decided to add Jordan to our destination because of its geographical closeness to Egypt and the interesting though lesser known sites that it presents to the archeologically and culturally minded visitor.

I will try to avoid boring the reader with a detailed itinerary of our trip, and concentrate on the highlights, observations, experiences and otherwise interesting facets of this journey through a region and culture that is rather distinct from ours.

We arrived, via Frankfurt – flying Lufthansa – in Amman, the capital of Jordan, erstwhile called Philadelphia by the Greeks, at the unearthly hour of 3:45 a.m. having flown over Jerusalem ablaze with lights with Haifa in the distance. Mercifully, we were whisked through immigration/customs by an able travel agent (A&K) and deposited in our Four Seasons hotel close to the center of town. On arrival there we had our first taste of the pervasive security in the region. Access to the hotel’s driveway was blocked by a submachine gun wielding sentinel and staggered Jersey barriers, followed by a magnetometer gate at the hotel entrance which beeped frenetically as we passed through. The alarm was, however, studiously ignored by the guard on duty, as we were accompanied by our A&K agent. Profiling is obviously the order of the day, and most of those high tech controls we were to encounter in Jordan and Egypt are utterly perfunctory.

After a recuperative snooze in our hotel room to which we had arrived before sunrise, we decided to take a walk in the vicinity of the hotel. We first explored a rather affluent residential neighborhood of Amman where almost every house had a Mercedes or BMW parked in the driveway. Our perambulations then took us to a commercial area with small shops and restaurants of humble demeanor from whose entrance we were frequently beckoned with inviting entreaties. Most importantly we felt thoroughly safe and unthreatened. The only adventurous endeavor was crossing any major thoroughfare – there were few if any traffic lights and the cars moved fast and did not seem too inclined to slow down for a pedestrian. Fortunately Evelyn and I can still propel ourselves with alacrity when so compelled.

Amman is a relatively appealing city because of its cream-colored buildings – the color of the local limestone. It is quite hilly – the customary seven hills are claimed and there seemed to be a building boom judging by the number of incomplete houses. Later, we were informed that all those jutting reinforced concrete columns sticking out above these buildings were a result of an idiosyncratic tax law under which owners were required to pay such building taxes only upon completion of construction. Ergo, such completion is delayed at infinitum. We were to find the same loophole in Egypt and, much later, in Turkey.

There are, however, shabby and miserable neighborhoods in Amman, especially on its outskirts where the displaced Palestinians live in rather squalid conditions. These areas had been their refugee tent camps that have been replaced by makeshift housing with limited infrastructure. The affluent, the diplomats and the government officials live in plush neighborhoods. The American embassy is a fortified enclave surrounded by armored vehicles with huge machine guns continuously manned by alert military personnel. No photos allowed as you drive by.

On the street, women’s dress ranges from the utterly Western – not too frequent – to headdress and long skirts to total black coverage with screened eye slits. We suspect that the latter are mainly Saudi women. Those who show their faces are often rather beautiful and very well made up. Sexiness is manifested mainly by tight-bottomed skirts.

On the next morning after our arrival we were introduced to our Jordanian guide, Mohammed – I wonder what fraction of the male Middle Eastern population sports that name or its variations – an affable mustachioed man in his 50s. He and the assigned driver were to be our companions for the next several days of our Jordanian sojourn.

The first site to be visited was about 30 miles north of Amman, the city of Jerrash, ancient Gerassa. It is now a dual city: a “modern” inhabited town separated by a ravine from the ruins of an ancient roman city. The latter is a surprisingly complete and impressive remnant of what must have been a major Roman center, a reduced but non-trivial version of Pompeii, with its typical cardum – the north-south artery of ancient Roman cities, lined with shops and fast-food vending stalls. The most notable sight of Jerrash is the enormous oval-shaped plaza-like forum completely surrounded by beautifully preserved columns, an architectural feature not seen even in Pompeii. Other interesting buildings were various temples, Roman theaters, a hippodrome, etc. Our visit was particularly rewarding because of the scarcity of visitors, and the overall serenity of the site. We had to reflect on the awesome extent of the Roman Empire and the astounding range of travels of Emperor Hadrian through whose arch one enters the Jerrash site. Years ago we had walked on and along Hadrian’s Wall in northern England, 2400 miles – direct line – from Jerrash. Hadrian would have qualified as a miles-accruing frequent traveler of Antiquity.

We completed the sightseeing day by visiting Amman itself, especially its highest hill on which there are more Roman ruins, and from where there is a sweeping view of the city including its centrally located Roman theater which we later visited.

The next morning, Mohammed and the driver picked us up from our hotel and we headed south along – what is called since time immemorial – the Kings Highway which is one of the three north-south roads in Jordan. The other two are the eastern Desert Road, and that which follows along the Dead Sea, in the west. Our main objective was the stone city of Petra which we reached late in the afternoon. On the way we visited several remarkable sites: Mount Nebo atop of which we had a beautifully sweeping view of the Jordan valley and from where Moses was alleged to have had a glimpse of the Promised Land. We then proceeded to Madaba where we saw the famous mosaic map from the 6th century (Byzantine) of the Middle East on the floor of a small church. Continuing south we visited one of several Crusader castles/fortresses that were strung for hundreds of miles from northern Syria to southern Jordan during the 12th and 13th centuries to defend from Moslem incursions against the occupying Frankish Kingdom. The ruins of these castles are rather impressive for their massive solidity and their elevated and unassailable emplacement. There is something incongruent, however, about the erstwhile presence of these mighty Christian military enclaves deep in what is now the heart of the Moslem world.

We then continued southward and, in the late afternoon, we arrived at Wadi Musa – the name of this town means Valley of Moses. This is the obligatory gateway to reach the highlight of all sites in Jordan – the rock city of Petra.

We stayed in Wadi Musa at a delightful Mövenpick hotel, and the next morning we were picked up by Mohammed – our guide – with whom we started our march into Petra.

Although this incredible site and its access are somewhat difficult to describe, I will make an attempt. Imagine walking from a relatively broad rocky/sandy valley (Wadi Musa) into a gradually narrowing gorge of high reddish sandstone which eventually becomes a winding chasm 10 to 20 feet wide – called the Siq – with a flat road-like bottom. Strange natural formations resembling huge animals, in some cases, alternate with human-carved shrines, statues, columns, etc. on the vertical side walls of this chasm whose length is about 3⁄4 mile.

Quite suddenly this narrow gorge opens up onto a natural plaza and you are confronted with the stunning view of what appears as the façade of a beautiful “baroque” Greco-Roman temple, prodigiously carved into the sheer reddish rock wall. This edifice, traditionally miss-named as the Treasury, has a beautifully carved frontispiece and can be entered – into the rock wall – reaching a large chamber with a flat ceiling. This carved temple and many of the additional monuments we were to see were created mostly by the Nabataeans, members of an Arab kingdom that flourished before and around the beginning of the Christian era.

We continued into a widening and meandering gorge with further stunning sites of rock-carved temples, tombs and other monuments, until we reached a wider valley with distinctly Roman ruins: an amphitheater, stone-paved column-lined street, a temple, etc.

Eventually we started the ascent – about 700 ft. – to the so-called Monastery (another misnomer, because of its eventual Christian use), another magnificent Nabataean carved façade. The rocky path was rather steep, including many steps, and our guide chose to ride it up – at least part way – on a donkey. The Lilienfelds, accustomed to more challenging climbs, managed quite well on foot.

Just above and beyond the Monastery there was a magnificent and sweeping view of the Jordan valley in the distance. As we reached this high point – about 3000 ft. above sea level – we heard loud thunder. The sky being of a deep and unalloyed blue, I immediately thought of sonic boom, and queried Mohammed about the presence of the Royal Jordanian Air Force to which he responded – a bit darkly – ‘No, the Israelis’.

We returned to our Swiss hotel in Wadi Musa late in the afternoon after having marched, climbed and descended more than 9 miles, and taken innumerable photos during a day where we never saw a cloud in the sky and the temperature ranged from about 60 to 70 0F.

The next day we continued our drive further south and eventually entered Jordan’s southeastern desert which flows insensibly into the never ending Saudi desert. At a highway stop we changed from our comfortable Samsung sedan to a 4-wheeel drive SUV driven by a strapping, good looking young Bedouin giant – he must have been at least 6- ft 4-in tall, and after reaching a rather modern outpost, entered the red-earth desert called Wadi Rum, made famous by Lawrence of Arabia where he gathered the Arabs against the Ottoman forces – Peter O’Toole was on-site to film that epic movie. A few Bedouin encampments dot the otherwise forbiddingly arid and uninhabited landscape of jagged peaks and sand dunes in various hues ranging from yellow to orange to deep red. We explored another extremely narrow Siq gorge with tantalizing prehistoric rock carvings of animals and women giving birth.

We returned to our highway stop bidding good bye to our gentle giant Bedouin, to start our northward drive, this time on the modern desert highway. We remarked that these new roads are remarkably good – built largely by an Italian contractor.

About 20, or so, miles before reaching Amman we swung west, and after passing a signpost indicating that we were at sea level, the road continued to descend for several miles until we reached the shore of the Dead Sea.

Mohammed had hoped that we could take a quick – and memorable – dip in the Sea, but it was too windy and cool, and I limited my experience to setting up my GPS altimeter to read just above the water level – it indicated minus 1386 feet, certainly the lowest point on the Earth’s surface.

We had a glimpse of the Judean Hills across the Dead Sea, and realized that we were closer to Jerusalem than Amman. We returned to the latter after sunset (about 6 p.m.), and took leave of our able and pleasant guide, Mohammed. He had left me, however, with mixed and somewhat disturbed feelings. He was an obviously gentle and relatively educated man, and yet he was also an uncompromisingly devout Moslem. I felt that biblical accounts, and the Moslem – and some of the Christian – mythology were as real and true to him as any fact can be. There was little or no room for rational explanations, doubts or any modern views. I saw him prostrate on a mat during a brief halt during our Petra excursion, although he could not have prayed the five times a day prescribed by his religion while he was our guide. At some point I mentioned my puzzlement about the Sunni-Shiite conflict to which he responded that it was a political matter, however, he expressed emphatically his strongly held opinion about the Shiites: “They are bad people”. His take on Saddam Hussein was that he had been less that perfect but that Iraq needed a strong-man leader. What is disturbing to me is that if a Jordanian in his relatively privileged position holds the views he did, What can be expect from the less “enlightened” majority? It struck me that he represented the Moslem counterpart of an American Evangelical fundamentalist – the difference being that he may well represent the majority of Jordanians against a – mercifully still – minority of Americans. We were to be similarly perturbed by our delightfully personable Egyptian guide on the Nile cruise. More about that later.

The next morning we departed from Amman on Royal Jordanian Airlines bound for Cairo, Egypt. This one-hour-plus flight was to take us not only from one country to another but, incidentally, also to another continent.

As our airplane was still sitting at the gate in preparation of our departure from Amman, I observed that the cabin TV screens were showing an odd image: the outline of the plane with an arrow at whose tip the word Kaaba was indicated. When the plane started taxying and turning, that arrow moved around as well. I suddenly had the ‘Eureka’ moment: this display was showing to the Moslem passengers the direction of Mecca so that they could face it, as required, during airborne prayers. This screen was then shown occasionally during the flight. After we took off from Amman, the display also showed the flight path. To my surprise, the plane flew with a south-eastern heading towards Saudi Arabia instead of south-westward to Cairo. The plane eventually swung over the Red Sea and then north-westward towards Cairo. All this deviation to circumvent Israeli territory. The flight would have taken one-half of the time if we would have followed the shortest path.

Again, at the Cairo airport we were received by and hustled through passport check by an A&K agent, and then taken with a minivan to our hotel, the Mena House. The drive took us first through an affluent suburb, Heliopolis, with large and stately mansions. Gradually, we entered into the swarming and sprawling city – of 15 to 20 million – where seedy neighborhoods alternated with less crowded areas, shopping avenues, mosques, modern high-rises, the walls of the old city – a teeming kaleidoscope. Traffic thickened as we advanced and became a tangled interweaving of multi-lane and crisscrossing chaos that our driver navigated unperturbed – renting your own vehicle would be engaging in extreme masochism. We crossed the west bank of the Nile to the suburb of Giza and proceeded south for a mile or two before reaching our destination. The Mena is the oldest hotel in Cairo. It is strategically located adjacent to the great pyramids. Indeed, our window view was filled with the imposing presence of the largest pyramid of all, that of Cheops, four and a half millennia old.

The next morning we were introduced to our Cairo guide Omaima, a delightful woman in her 40s, impressive in her well dressed and appointed countenance. She was, quite obviously of the Egyptian upper middle class and her only subtle concession to Middle Eastern feminine sartorial reticence seemed to be a thin turtle neck.

We were chauffeured around Cairo by the able and calm Mahmoud, our driver for that city. Our first stop was the famous Egyptian Museum of which we visited only the first floor, having planned to do the second after our return from our Nile cruise, in order to avoid museum saturation. It is an impressive gathering of incredible Egyptian art, as expected, although the building is rather old and with insufficient space to exhibit the, apparently, enormous trove of artifacts that are in storage. A new museum is purportedly being built elsewhere in Cairo. The crowds were a bit intimidating at the entrance but once inside the relatively large space diluted the throng’s density.

After lunch in a characteristic but rather elegant restaurant we explored the citadel, including a couple of mosques, and parts of the old quarter with narrow shop-filled alleys. The city is remarkably dynamic, intense and surprisingly varied. One of the unexpected impressions was the feeling that petty crime is essentially inexistent, and that one felt safe, welcome and unthreatened. Considering the magnitude of the city’s population and the politico-religious tensions of the region, these impressions were indeed surprising.

Air pollution is elevated and a lot of the time there is a distinct haze in and around the city. A rather distinctive feature is the forest of TV satellite dishes that cover essentially all roofs, high or low. In the hotel room, there were many Arabic TV channels, including Al-Jezeera, Al-Arabiyya, etc. All rather incomprehensible to us. But there were always the BBC and CNNI, as well as various European channels for our western ears. No sign of any Israeli TV.

As in Jordan and during our Nile cruise, one sound is utterly pervasive: the call to prayers of the muezzin. This occurs five times a day, issued from horn-shaped loudspeakers protruding from the sides of all minarets. It is a rather unmelodious, grating call. On Fridays, the equivalent of western Sundays, the chant – if that bellyaching howling qualifies as such – continues for excessively long stretches. No sign of heartwarming European bells.

The subsequent day we were taken to a site about 20 miles south of our hotel, to Saqqara. The most notable monuments there were the mastabas (very ancient low strung burial buildings), the first stone funerary temple in Egypt (and presumably in the world), and the stepped pyramid of king Djoser (who governed from 2630 to 2611 BCE), the precursor of all pyramids.

It was here at Saqqara where, for the first time, we became aware of the sharply defined geographic boundary between the green belt bordering the Nile river and the world beyond – the desert. As we were to see time and again, as we cruised up and down its river artery, Egypt is the Nile. For the 700, or so, miles that it flows South to North through Egypt, the river creates an agricultural and inhabited strip that ranges from a few hundred yards to several miles on either side of the Nile’s banks. The abruptness of the discontinuity between the green belt and the sandy/rocky wasteland on both sides is startling. You can actually put one foot in the greenery and the other on the sand. Frequently, the desert boundary is defined by a steep sandstone cliff, probably created by the millennial recurrence of the annual Nile floods.

The eastern desert extends to the Red Sea, whereas the western one is the Sahara itself which goes all the way across the widest part of Africa, for thousands of miles. Only at the large delta mouth of the Nile, as it flows into the Mediterranean, does the river basin become very wide and the green belt expands correspondingly. Another peculiarity of the Nile is that it has no tributaries as it winds itself through Egypt. Water is removed from the river by irrigation channels and small private pumping stations whose put-put provided us with the only occasional noise as we cruised along.

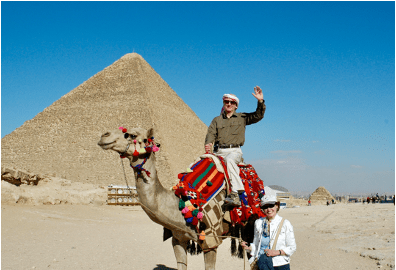

Later on that day we paid an extended visit to one of the most stunning of all monument complexes in Egypt, the pyramids of Giza and the Sphinx. This site is located at the very desert edge of the Giza suburb of Cairo. The innumerable pictures we have all seen of these pyramids do not do justice to their awesome appearance when standing nearby. There is a basic beauty to these structures because of their essential design purity and simplicity. I entered the shaft of the second largest pyramid all the way to the centrally located funerary chamber. A long crouching descent in a stiflingly impure atmosphere which Evelyn chose to forgo. Outside, we were cajoled into camel photography by a wily Tourist-attuned Egyptian. It was my first camel riding – rather, sitting – experience. One must hold on for dear life when the animal rises or lowers itself, lest you fall over its head.

Near the great pyramids is the Boat Museum, an elongated structure that houses a stunningly long Nile boat found – disassembled – in one of the ancient tombs, one more artifact to be available to the king in his afterlife (I wonder if his soul was expected to assemble the boat, a task that took twenty-five years for a large team of archeologists).

This brings me to the subject of the art and architecture of ancient Egypt in which we were to be submerged for about two weeks. Three related aspects of the Egyptian treasures were to stand out: a) their staggeringly long age span – starting more than 3 millennia before the current era to about 500 AD; b) the ritual rigidity and invariability of style and subject over that enormous time span; and c) the recurring and all pervasive obsession with the afterlife as the driving motivation to create this staggering architectural, artistic and documentary corpus.

The next morning we had to rise at an unearthly hour to catch our 4 a.m. flight from Cairo to Abu Simbel, at the southern end of Egypt, a few miles from the Sudanese border. Abu Simbel is a repositioned temple complex that was lifted to higher ground prior to the flooding that created lake Nasser in the 1950s when the Aswan dam was completed. The most notable aspect of the Abu Simbel site are the colossal seated statues of Ramses II at the entrance of his temple carved into the rocky hillside. Our visit, however, was marred by the throng of tourists visiting the interior of the temple, our only negative experience during our exploration of many sites during the sojourn through ancient Egypt.

After Abu Simbel we were taken to the Aswan dam, a major engineering accomplishment that had been supported principally by the erstwhile Soviet Union. The closure of this dam engendered lake Nasser, a large body of water that extends into northern Sudan and which drowned a number of villages and archeological sites with the exception of Abu Simbel and the magnificent temple complex of Philae on an island that we visited after seeing the dam.

Eventually we were taken to our Nile vessel, the Sun Boat III which was to be our moving abode for the next week, and we departed Aswan northward bound to visit the most alluring series of sites in the Nile stretch up to Abydos. These included Kom Ombo, Edfu, Esna, the unique complex of Thebes (Luxor, Karnak and the Valleys of the Kings and Queens), and Dendera.

I will refrain from describing these sites since that is not the purpose of this, already extended, letter. Suffice it to say that they are worthy of a string of laudatory adjectives. These archeological treasures leave one speechless and surprised that so much artistic and architectonic beauty has survived over such a mind boggling span of time. Another, to me, surprising aspect is the degree to which the ancient Egyptians documented their history in stone combined with our ability to decipher and decode this information treasure.

The boat ride on the Nile was a delightful experience. The crew on board was a youthful, enthusiastic and engaging group of Egyptians, and the archeological guide was the knowledgeable, pleasant and soft spoken Tamer Farouk who made his presence known lifting his ever present bottle of water over the heads of other visiting groups. But there was a darker side to this otherwise engaging young man and it became apparent after an on-board slide show. The eerie similarity of his socio-religious convictions to those of our Jordanian guide Mohammed surfaced as he saw fit to expound briefly on his views about women and the concept of jihad. On the former subject he justified polygamy with a sophistic reasoning: it is designed to protect women from – the apparent inevitability of – masculine adultery. About the idea of jihad he affirmed that the word had no intrinsic connotations of aggression but that it merely signified a noble quest. His thoroughly earnest discourse drew a stony silence from the gathered cruise passengers, mostly Britons, Aussies, Dutch and the Euro-American Lilienfelds. I was left with the unsettling and disturbing impression that the great European Enlightenment never shone on the Moslem world, and that our two civilizations are more than ever like ships passing in the night. We had encountered two, in all appearances, warm and intelligent human beings whose mode of thinking had been thoroughly molded by a religion whose orthodoxy left no room for any deviation from a set of medieval rules. Such complete brainwashing can, under “appropriate” conditions lead to the justification of essentially any action be it beneficial or abhorrent. I could not but recall Steven Weinberg’s (Physics Nobel prize winner, 1987) biting aphorism: “Good people tend to do good, evil people tend to do evil, but for a good person to do evil – that takes religion”.

As our boat navigated the Nile we witnessed the persistence of a modus vivendi along its banks that has barely changed over the centuries or perhaps even over the millennia. Agriculture, livestock-raising and fishing seems to proceed without much awareness of the outside world. We passed small ancient looking settlements, women washing their clothes, themselves and cooking pots in the river. Life seemed to proceed at an unhurried pace mostly oblivious of the cruise boats passing along, except for an entire student body screaming enthusiastically from windows, balconies and terraces of a school as our boat passed by in a section of the river where few cruise boats are seen.

As far as visiting the various archeological sites, security followed the general pattern of being pervasively present but, in all appearances, potentially ineffectual against any truly organized attack. It was thoroughly entertaining to be preceded by a siren-wailing small pick-up truck loaded with guards wielding submachine guns whenever we were taken by bus from the dockside to a temple at some distance from the river, such as at Abydos. All other vehicles on the road, trucks, cars, donkey carts, bicyclists, had to move aside hastily before our barreling VIP convoy.

During our stay in Luxor – the ancient Thebes – Evelyn and I were convinced by our guide Tamer to take a balloon flight over the Valleys of the Kings and Queens. This was our first such flight in a “lighter-than-air” conveyance. It was a marvelous hour-long experience starting just before sunrise (when wind is usually at a minimum). The basket hanging from the hot-air balloon carried nothing less than 32 passengers in 8 compartments for 4 people each. It is a totally noise-less experience interrupted from time-to-time by the blast of the burner that heats the air inside the balloon. We traveled sometimes at grazing heights over the sugar plantations, and occasionally rose to about 500 feet above the ground. The views were stupendous and numerous photos are testimony of our impressions. When we landed – bumping along a bit – we were received by chase vehicles that had followed us. At least a dozen such balloons had been aloft together with ours.

Finally, our Nile sojourn ended and we flew back to Cairo from Luxor to which our boat had returned after reaching Abydos farther north.

We completed our visit to the Egyptian Museum and the old quarter in the company of our erstwhile guide Omaima, and Mahmoud, the able and quiet driver.

We returned to Boston via Frankfurt, feeling that we had experienced a bit of Thousand and One Nights though tempered by some harsher realities from which we were shielded, most of the time, by the kindness and warmth of those who took care of, and guided us, and by the comforts that surrounded us throughout this trip.

Leave a comment