Incongruities Galore

The vast majority takes for granted that we all are citizens of a specific country — usually but not exclusively the one where we were born. This reality also implies that we have the right to possess a passport that attests to that citizenship and with which we can travel to other countries.

What happens, however, when that citizenship assumption proves to be illusory and out of reach?

Here is the story of my family’s and my citizen and passport vicissitudes.

My parents were born German-Jewish. Their family’s German ancestry went back centuries. When they abandoned their homeland in 1933 as a result of Hitler’s takeover, they travelled to Spain as German citizens bearing corresponding passports.

I was born in Spain a year later and it was assumed that — following my parents’ citizenship — I was also a German. This was based on the then illusory belief that Hitler’s grip on power was a passing cloud, that the German people would soon come to their senses and restore normality to their country ridding themselves of that maniac and thus allowing my family to return to Germany and resume their interrupted life there.

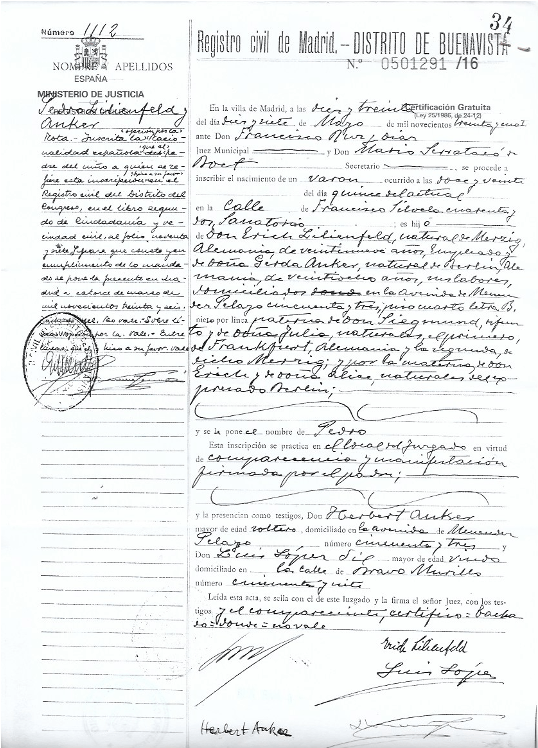

After about three years in Spain, however, my parents came to the realization that a return to German normalcy was indeed illusory and that our foreseeable permanence in Spain was to be planned for. Consequently, in March of 1936, when I was just short of two years old, my parents opted for my Spanish citizenship which was duly and officially inscribed as an afterthought on my birth certificate (see below, scribbled on upper left side of the certificate).

Destiny and history, however, had their own plans. Four months later, in July of 1936, Spain exploded in its fratricidal Civil War and my family’s intentions were shattered. Unable to be admitted to the U.S., we moved precipitously to Paris.

In France, normality appeared to be regained for my family and I. My parents continued to bear German passports and I was, as per my birth certificate, a Spanish citizen.

Three year later, World War II begins and we are dragged into its maelstrom. My family is immediately classified by the French authorities as German enemy aliens. Distinctions between Jews and non-Jews were, for the French, irrelevant figments. My father is placed in an internment camp and my mother, her parents and I are forced to relocate to a town in western France. Our ensuing vicissitudes are documented in my autobiography.

Let us vault over the next perilous 18 months, and we manage to escape, miraculously, back to Spain. My parents have to legalize their status in Madrid and are required to present themselves at the Nazi German embassy in that city where they are summarily deprived of their German passports that identified them as Jews, and they become citizen-less.

I am seven years old, at that point, and the only one of my family possessing a citizenship, albeit without a passport, given my age.

Again, the efforts of my parents to emigrate to the U.S. prove to be fruitless and we travel to Ecuador where in 1942 we arrive when I am eight years old and where we were to live for 16 years.

My family and I never acquired the Ecuadorean citizenship because it required a convoluted legal and costly procedure involving, at the time, the personal authorization by the President of the country.

I, however, remained, de facto, a Spanish citizen and on that basis I presented myself, at the age of 21, at the Spanish embassy in Quito to request a passport in order to be able to travel out of Ecuador for the first time since my arrival there as a child. The Spanish functionary at the embassy informed me that they could issue a passport but that the first page of that document would indicate that I was a fugitive from the military service — prófugo del servicio militar — given that I had not fulfilled that duty, as required. This, however, would have been a most undesirable designation given that I needed to stop over in Madrid on my way to Paris.

So, passport-less, I am constrained to travel internationally bearing a temporary travel document issued by the Ecuadorean government, an elongated officially looking sheet of paper with seals of the foreign ministry, and on which the visas of the countries to be visited had to be incised by their respective embassies in Quito.

Who has ever travelled unfolding a document in lieu of a bona fide passport? Yours truly, indeed. And I was to become aware what kind of an international deviant I had become as a result of such a heterodoxy.

I had no problems traveling from Quito to Paris. On my stopover in Madrid the Franco authorities never suspected that I was a “fugitive from the Spanish military service”. A few weeks after my arrival in Paris at my grandmother’s home I departed for a quick three day side trip to Germany to take care of my father’s business matters. I was in Hannover after finishing and, who knows why?, I looked at the visa on my famous travel document cum passport and, to my horror, discovered for the first time that under the French visa stamp there was, scribbled in minute handwriting, the note une entrée – one entry. Even my travel inexperience suggested trouble.

I decided to immediately go to the local French consulate to forestall such trouble when landing back in Paris. I have described my unpleasant consular experience in my autobiography: I was simply booted out from that consulate as a pariah. Same experience followed the next day at the French embassy in Frankfurt. You cease to be a member of humanity without a recognized passport booklet. Intervention of my influential step grandfather, the conductor at the Paris Opera, had to be telegraphically enlisted with, no less than, a ministerial decree with which I was anointed by the French government and that legislated my unlimited future access to France. I swore to myself to never again travel as an “uncivilized” passport-less pariah.

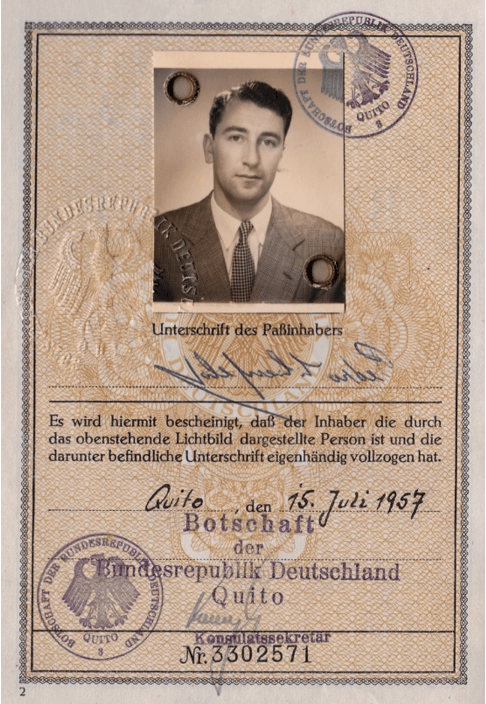

In 1957, the Federal Republic of Germany decided to offer to restore German citizenship to those who had lost it to the Nazis, such as my parents. They accepted and thus, I was also entitled to the same status, although I had never lived in Germany and was, still officially, a Spanish citizen.

Now, as can be seen from the first page below, I had finally acquired a bona fide passport which, eventually, allowed me to travel unhindered to the U.S., first as a visitor in 1957, and then as a student in 1958, classified by the American embassy in Quito as a “nonimmigrant” entitled to “multiple applications for admission to all United States ports of entry”. What an irony! During the war, when we most needed it, we were not admitted to the U.S. Now, as a German citizen, I was welcome to this country. In 1960, on our honeymoon, I travelled back to Ecuador and then to France, Switzerland and Italy with that spanking new German passport.

There was, however, one drawback to that German citizenship: it prevented me from receiving a Fulbright scholarship in Ecuador to which I was entitled, having graduated at the head of my engineering class in Quito but for which I would have had to be an Ecuadorean citizen, as stipulated by the American embassy there.

Now, to become a resident to the U.S., after my return from our honeymoon, however, the German citizenship became irrelevant. Why? Because the American immigration laws then counted the person’s birthplace to determine the applicable immigration quota. That would have been Spain in my case whose quota had a waiting time of merely 30 years! Fortunately, I had married a U.S. citizen and, on that basis, I was granted resident status.

In 1963, I acquired U.S. citizenship. I only needed to reside here for three years based on the fact, again, of having married a U.S. citizen. This step had been suggested to me because I was, at that time, working on a project supported by the Atomic Energy Commission. The citizenship examiner refused to accept my idiosyncratic mirror writing signature (see above example on my German passport) alleging irascibly that it had to be a “Christian signature!”. Thus, I just wrote my name in lieu of my signature. I should also mention that prior to my citizenship ceremony I was provided a pamphlet published by the Daughters of the American Revolution wherein U.S. history started with the landing of the Pilgrims, ignoring entirely that there had been Native Americans here and the Spaniards had explored North America well before any English arrived in North America. All this, fodder for my erstwhile doubts about coming to this country.

Is this the end of my convoluted story? By no means. I have applied for a German passport, a renewal of my old 1957 one, expired long ago. I am also considering to request a Spanish passport. Why? Blame it on Donald Trump. Even the most remote possibility of his renewed accession to the presidency of this country has triggered my most innate fright/flight survival/escape instinct.

Last but not least, I’m asked sometimes whether I feel allegiance to a specific country. Do I feel American, or Ecuadorean, or Spanish, or German, or whatever? My answer is none. I am an American citizen, but I don’t really feel “American”. I am thoroughly grateful to Ecuador for having received us with open arms when we needed it and other countries were barred to us, but I do not feel Ecuadorean. I was born in Spain but I cannot classify myself as a genuine Spaniard. My mother tongue, if I have any, is probably German but I do not feel any allegiance to Germany. My schooling started in French but I am not a Frenchman. I feel deep affinity to the Spanish language and culture but the language in which I write is preferentially English. A possible, but imperfect, identification that I can come up with, perhaps, is that I am a deracinated Western European of Ashkenazi descent.

A Bit Of Passport History

If we are talking about the history of passport, we must mention whoinvented the first passport. King Henry V of England is credited with having invented the passport we use today. The earliest reference to these documents is found in the 1414 Act of Parliament. In 1540, granting travel documents in England became the role of the Privy Council of England, and the passport term was used around this time. A passport issued on June 16, 1641, and signed by Charles I, still exists. In 1794, issuing British passports became the job of the Office of the Secretary of State. The records of every English passport issued since then are available. They were available to foreigners and were written in French until 1858.

The rapid expansion of rail infrastructure and wealth in Europe, beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, led to significant increases in international travel and a steady decline of the passport systemduring the nearly thirty years before World War I. Significant increases in the number of people that crossed the border have made enforcement of passport laws difficult. In the later part of the nineteenth century and up to World War I, passports were not required for travel within Europe, and crossing a border was a relatively straightforward procedure. Consequently, comparatively few people held passports.

When were passports first required? Generally, no international passports were required until World War I. During World War I (1914-1918), European governments introduced border passport requirements for security reasons and to control the emigration of people with useful skills. In general, it was necessary to put in place a control system, as the number of immigrants had increased dramatically due to the war. These controls remained in place after the war. Though these new rules and changes were controversial, the procedure has become a standard. British tourists of the 1920s complained, especially about attached photographs and physical descriptions. These passports included details such as “face shape,” “skin colour,” and “facial features,” along with the photograph and the signature. Characteristics of these details were as follows: “The forehead: Wide; Nose: Big; Eyes: Small,” etc. Indeed, people considered it degrading and humiliating.

Leave a comment